Other Writing

by W.S. McCallum

The Naked City

There are a thousand stories in the naked city - this is one of them:

The Square 5.00 p.m. - fairly empty. A thin scattering of the Square's regular habitués are dispersed around the dozen-odd places that they regularly frequent. In between is the odd nervous looking pre-adolescent, waiting for the bus home after the two o'clock session. There's a noticeable foreign presence - a couple of Japanese couples looking around in vain for a shop that's open.

By the corner of the Post Office building, a down-and-out lies sprawled out on one of the seats, dozing. In his late fifties, he wears a tatty old dark green suit, and the fragrance of alcohol and sweat rises from his body. An American tourist, a fan of cinéma vérité, creeps around him, taking snaps from various angles. Her camera is worth about $300 more than the empty bottle of whiskey the sleeper has discarded near the seat. She carries spare photography paraphernalia in a shoulder bag and is meticulous in getting the correct angle and distance for each shot, carefully pacing it off. The drunk dozes on, oblivious to his immortalisation on film.

Around the corner sit five brightly-clothed Tahitian teenagers. They smoke, occasionally hug one another and chat loudly in French, occasionally bursting out in laughter. The two boys wear U.S.-style numbered t-shirts, one emblazoned with the letters HAWAII in screaming red. They resemble a junior francophone version of your real kiwi joker. Eventually one of the girls goes to a telephone box. She calls for help from one of her friends as they decipher the English instructions on the wall of the booth. Finally, she gets through. They must be staying with locals, because she speaks in English. "Âllo...... Yes, ve are an de Squooere." Eventually they traipse off into the distance to get picked up by their hosts.

The Square 6.45 p.m. - Teenage courtship rituals: Two Polynesian guys, about 15, sit together waiting for the bus. Across the Square from them sit three girls, mimicking their every movement. After a few minutes, the guys finally latch onto the fact that all this activity is designed to attract their attention. They seem rather taken aback. "Whaddya reckon…" asks one, "Ya wanna chat 'em up?" His friend has cold feet: "Nah, the bus'll be comin' soon." The pair content themselves with waving back. The girls persist. They move to a closer spot and start eyeing their prey. The reluctant one gets even more edgy. His friend is just mustering the courage to say hello when their bus arrives. The pair cut and run. As the bus pulls out, the girls wave while the pair on the bus try studiously not to look embarrassed by all the attention they're getting. As the bus vanishes in the distance, they spot me watching the whole spectacle. I ask them what school they go to. They're fifth formers from Girls' High.

The Square 7.00 p.m. - It's getting colder and a slight wind blows over the paving. A wave of buses arrives from various suburbs and disgorge their contents. A trickle of people spill out of the hydraulic doors. They wash around a little island of "street" kids huddled on the steps in front of the Cathedral, who have just come into town themselves after completing their evening meal at home. They make a good show of looking street credible but none of them ventures out from the group alone.

The Library 7.40 p.m. - The occasional yuppie couple wander in for a pre-show browse, as does a pack of six schoolgirls, out for a night on the town. As they climb up the escalator, they laugh and cast glances at two 17 year-olds coming down the other way. The two boys wait for them outside.

8.00 p.m. Chancery Arcade - Nightclubbers trickle into the arcade. The males sport short haircuts and loud shirts; the females tight skirts, high heels, copious amounts of make-up, hair gel and tacky jewellery.

8.35 p.m. The Square - It's getting dark now. The "street" kids are still there, but have relocated to the foot of the statue. A pair break off from the main body and saunter around the Square. "Ya got 20¢..?". "No". They wander off to the next victim, mock dejection on their faces.

9.10 p.m. Colombo Street Overpass. The van owners’ association have gathered with their wheels under the flyover. They lounge on the bonnets of their cars, sinking half g's. Denim is "de rigueur", as are beards or moustaches. Hair is longish. Their girlfriends belong to the 14-16 age group. Deep Purple plays from a car stereo. One of them accidentally drops his half g, creating a loud crash and the noise echoes around under the traffic passing overhead.

9.50 p.m. Colombo Street, Sydenham - A Vauxhall, driven by a real kiwi joker and his mates, cruises past. Its occupants loudly inform me of my supposed homosexual tendencies through an open window.

10.00 p.m. Colombo Street - Walking along the footpath, I overtake a couple from behind. The male - early 20s, blond, clean-cut with a moustache. He has a rugby player's physique. His lady friend has long, blond hair, permed. She wears a tight black dress and high heels. She seems agitated as I approach. "Why don't you listen to me..! You never listen! I'm speaking to you!" He continues walking beside her, not saying a word, his eyes averted. She slaps him in the face. Hard. If he wasn't paying attention, he is now. He explodes. "You bitch!" He grabs her and pins her to the wall of a shop. "Don't you EVER fuckin' do that again! Ever!" He spots me coming nearer. "Come here" He pulls her away from the bright lights of the street into an adjacent, dimly-lit carpark. I don't hear their heated words as I pass by, they're too far away. I do a U turn and go back to see what's happening. They stand in the shadows, hugging each other. He does the strong, silent act while she cries on his shoulder.

10.15 p.m. Colombo Street, City Mall - Two women strut on the footpath, trying to look as visible as possible to the male drivers of passing cars. They get a couple of honks from car horns, but nothing else is forthcoming. They both look like they're in their late 20s, but they're probably younger. Their faces have a lived-in look. They're from Auckland.

"Too much with the cops up there, too much competition. I was in a massage parlour eh... But the guy there started gettin' bossy, started hitting me. He beat me up. We came down here 'cause it's quieter... Too quiet. Yeah, it's hopeless some nights. Like Monday, we were out till 12 - didn't get one offer". Her friend nods. "Yeah, it's just dead here during the week".

"The cops... Yeah, they're gettin' worse. We used to stand down there". She points to the BNZ building. "But there were too many cops cruisin' around. Just before, a car of 'em pulls up and one of them sticks his head out and says "come here! What's your name?" Shit, I just turned 'round and walked off and they followed me. After a while they drove off."

10.30 The Square - The pictures have finished and the Square is full of teenagers waiting to catch the bus home: More courtship rituals. Two boys stare, wave, shout at, and eventually approach three girls. They hit it off. One of the girls breaks off from the group and comes up to where I'm sitting. "Hi, I'm Susan. Have you got a pen? We want to get each others' numbers." While I look around for a pen, she asks me how old I think she is. I guess. She smiles and adds confidentially, "No I'm only 14." She looks over at the two boys standing a few paces away. "Don't tell them though, they're 17!" She wanders over to them with the pen and then brings them all over to say hello to me. The two guys pay more attention to them than me, not surprisingly. A few minutes later their buses arrive and it's time to go.

11.00 p.m. Outside the Palladium - An incredibly drunk woman, barely able to stand on two feet, is being restrained by half a dozen well-dressed friends. As I walk past, she suddenly lunges out at me, screaming "You bastard! Arsehole! Look what you fuckin' did to me! Bastard! Baastaard!" Her friends manage to hold her down. I give them an "I've never met this woman in my life" look and they return it with an "It's OK, she thinks you're someone else" one.

11.10 p.m. Riccarton Road - I'm walking past a takeaway bar when a drunken old man appears, coming the other way. He mutters something to a couple walking in front of me, who turn around to smile patronisingly at him. He spots me as I get closer, and issues a challenge "You'd better watch it mate! I was a soldier I was. I was!" I don't doubt him. He's easily in his late sixties, possibly older. He hasn't shaved in a couple of days. He mumbles something else in my direction. I excuse myself and say I'm sorry but I can't understand what he's saying. As I walk on, he cries out again. Deprived of the confrontation he was looking for, he almost sounds desperate. "I was a soldier, I was, a soldier..."

His voice fades away as I walk further homeward.

Originally published in CANTA No. 4, 22 March 1987 pp. 8-9.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum March 1987.

A Touchy Subject

Attitudes, towards the once taboo subject of adoption are changing. In the days before the Pill and the Domestic Purposes Benefit in New Zealand it was that or marriage for many women. Nowadays groups like Birthlink encourage people to talk about their experiences of adoption and adopting. CANTA reporter Wayne McCallum listened to the experiences of four varsity people.

Last year, the Adult Adoption Information Act came into force. From 1 September, adopted people over 20, and those who had adopted out, could apply for a full birth certificate giving both birth and adoption information providing a veto had not been placed by the adoptee or parent beforehand. So what's this got to do with you? Back in 1967, around the time most undergraduates were born, 27% of first-born babies born to mothers between the ages of 16 and 25 were born to unmarried women. Social conditions at that time made the prospective solo mother's lot a very hard one. The social welfare system made no allowances for them. Abortion was not freely available. For many, adoption was the only choice for their children. Chances are that you know some of those children, or are one yourself. Here are the adoption experiences of four people from Canterbury University.

Elaine

I was about 12 or 13, and found out after a sex education talk at school. My adopted mother sat my sister and I down around the fire, and told us we were adopted. I always knew I wasn't the same as my parents because they're very quiet people. I'm totally different - I say what I think. So I always knew there was something different about me because I could sense it.

My self esteem definitely dropped. I went through a stage of rebelling against my adopted parents. I left school when I was 14. I loved my adopted parents, but I put them through hell, and they put me through hell too. I felt as though I was unloved, unwanted, so I went out and slept around, trying to find that care and closeness that I felt as though I had lost. I wanted to find my birth parents right from when I found out I was adopted.

I had been told there was no way at all you could find out who your real parents were. There were no avenues open whatsoever. I think until about three years ago the Social Welfare Department wasn't actually giving out non-identifying information either. Once I got my non-identifying information (this was about two and a half to three years ago) that was enough for me to start off with. All they could give out at that time was my birth mother's age, his and her occupations, and their colouring. What they did was actually type out what was written - there's no names, no addresses. It just said that my birth mother wasn't very tall and that sort of thing, and medical information.

After that I waited. I got told by the Social Welfare Department that there was going to be an Act passed. Once the Act was passed I got my form to fill in and wrote off for my birth certificate. I got back a veto, which I had to put aside at the time because 1 had assignments due. After a month I finally started to deal with the veto.

It was very devastating. It was like being rejected all over again because I admit that when I found out I was adopted I felt as though my birth mother had rejected me. Getting the veto, I felt as though she were rejecting me again. She didn't want to know anything about me and that was it. I thought "I'm going to get this bitch. If it's the last thing I do I'll get the old cow".

There are means and ways of finding out. I went along to the Adoption Support Group and found them really supportive. I don't really want it to be publicised how I found out, because it is illegal; but it's something which they've used for years.

I rang her up. She denied the fact she was my mother. It took me 10 minutes to convince her and I was apologising profusely. I thought "here's some poor woman and I'm accusing her of being my mother - and she's not my mother!" I kept saying "God, I'm sorry. This must sound terrible, but I can't understand someone else using your full name." Because she was Catholic and her confirmation name was on my birth certificate as well.

She said, "Oh, stranger things have happened."

I said, "I realise you've come from a large family. You don't think it could have been one of your sisters?"

"Oh", she said, "I left home at an early age. I wouldn't know whether or not it was them."

"You won't mind then", I said, "if I contact them. I realise some of them don't live in the South Island, and I'm going up north. I'll contact them while I'm there." I kept apologising and going on like this and I said "Thank you, I'm sorry I upset you".

That was when she turned around and admitted she was my birth mother.

My birth mother actually came and visited me one day. When she was initially going to turn up, I kept thinking "God, is the place clean enough? She's going to look around and see dirt somewhere". I rushed around cleaning up and everything. When she walked in, she sat down and I said "Aren't you going to say hello?"

She said "No, I don't want to be here".

And I thought "My God, how do I handle this?"

She turned around and said that she didn't want to know anything about me. She didn't want me when she was pregnant with me, and she didn't want me now. And she started swearing and carrying on. I mean, I can swear with the best of them, but when this woman sat down and said "fuck" in my lounge, I just looked at, her and thought "My God!" It was a real eye opener: It was very hard to take but I don't believe that a woman can sit opposite another person that's part of them and turn around and say that. I don't think there can be anyone that cold and cruel out there. At times it gets me down.

All adopted people have this feeling - this fantasy. We live in a fantasy land. We either think that our birth mothers are prostitutes or druggies, or we think they're someone high up in the community. We have no idea what our birth mothers or fathers are like. I've been told that my birth father was the man down the road and that's probably all I'm going to find out about that. We live in a fantasy land until we actually meet them.

I know who I am now. I know who I look like - I know I look like my birth mother. Most of what I found out about my other relatives was through my birth mother's sister. I'm very friendly with my aunty. I'm still getting through the situation. I understand a lot more now than I did originally. Adopted people go through a lot of problems. They find it harder to make relationships last, and to form relationships, because you're always searching for something and you don't know what it is you're searching for.

David

As far as I know, my real parents were varsity students and their parents didn't agree that they should get married, but they wanted to. So they put me up for adoption. My name was given to me by my (adopted) parents. My mother, she had a child and it died of cot death, so they adopted me. It's very hazy - after something like four months my mother collected me from Auckland. They tried to have another child and that one died as well, so they adopted my brother, and they wanted a girl, so they adopted my sister.

My parents have always been very honest, and they told me right from the start that we had all been specially chosen. It has never been kept a secret. I'm quite honest about being adopted. I've been walking down the street with my parents and people have said, "How can you be related?", cause mum and dad are really short and I'm quite big. And I've said "I'm adopted". There's been no qualms about that. People have said "Do you want to meet your real parents?" and I've thought "I'll come to that when it arises". And it has. My biological mother tried to get in contact with me the day I turned 20. She wrote to Wellington, which is where they have the headquarters, and they tried to get into contact with me. Through the electoral roll they wrote to my old address in Riccarton. I'd left there and they still tried to track me down, but they couldn't find me.

Then they wrote a letter to my parents specifying that she wanted to get in contact with me. My parents just left it up to me really. They had reservations, but they said, "it won't offend us if you try to find out".

The letter that she wrote was given to me. My biological mother doesn't actually know I've got this letter, or that I even exist. The letter explains about her. She's 39, married and doesn't have any other kids. She's a sales rep for a world-wide cosmetics company and her husband owns his own national company. For some reason I always imagined they'd be rich. That's the bit that bothers me about the letter, and there are other parts that bother me.

There's a sentence here that says "My husband and I would be happy to welcome me into their home should the situation occur". It's sort of hinting that I want to make up for something. The other bit that really bothers me is "I would be prepared to pay any travelling expenses to or from a meeting". They live in Greenlane, Auckland, which is really prestigious, so they're quite well off. I don't know whether they are, but I've got suspicions they're trying to use money as a bait.

She might think I want to "make up" for all those years, or she might want to make up for something and I don’t want that. But it's really tempting because I'm not that well off at the moment either. That's the bit that scares me. Obviously, she wants to know what I've done with my life. I think a meeting would be the best, and I don't want to take advantage of her kind offer. I was going to write and say "come down here". I haven't done it yet. It's been three or four weeks and I'm still sitting on it.

It's one of those things that you really don't know what to do about. When I first got the letter I thought "No, I don't want anything to do with it. My parents are really important to me, because they raised me and they might have thought it a bit of an insult that after all these years I'd still want to see this person. But it's important that she knows I didn't die when I was six, or end up in Mt Eden - that I came out alright and that she made the right decision.

When I go to this lady, she's not going to be my mother, just another friend who I've got something in common with. We'll never be close. We'll never be mother and son; definitely not just friends.

John

When I was first told I was adopted, it was like having a bomb explode in my face. I walked around shell-shocked for the rest of the day, just going through the motions of my daily routine. My whole self-image was just blown apart. I was no longer who I thought I was. My parents weren't my "real" parents. My name wasn't my own.

I later felt used. I was full of hate and loathing as a result. How dare this woman dump me! How dare the State auction me off to the highest bidders, like an old umbrella left at the lost and found!

It took a couple of months to get out of that state; although if I'm in a bad mood I'll occasionally go back to thinking like that. By that time I'd successfully destroyed any relationship I might have had with my girlfriend. Mentally, I took a step back from her, and slammed and bolted shut the little compartment where I shovelled all my adoption hang-ups. She came to realise I was keeping something from her, and things rapidly deteriorated from there.

Things didn't change much with my adopted parents mainly because we had so little contact with each other anyway. After they told me, I didn't mention it again. There seemed little point. All it did was upset my mother, who seemed less able to cope with the issue than me. She probably had visions of this other woman coming and abducting me at gunpoint. I had my own problems, I didn't need hers as well.

I clung to my schoolwork as a way of avoiding things. There was a simplicity there that I liked: You got your work, you did it, and you passed. It was a little world where I didn't have to worry about upset mothers, a collapsing personal life and all the rest of it. Then, once exams were over, I had almost four months of free time stretched out ahead of me. There was no more schoolwork to hide behind. I eventually faced up to the fact that I could go through the rest of my life feeling bitter and not knowing who the hell my mother and father were, or I could get off my backside and do something to find out about it.

So I did. I didn't tell my adopted parents anything about it at the time. I didn't want my mother, who was capable of being quite neurotic about the matter, breathing down my neck, placing more doubts in my mind than already existed.

I'd initially placed a veto on my birth certificate, partly because of my adoptive mother, partly because of my own fear of the unknown. I took it off. Luckily, no one had applied for a copy of my birth certificate, or put a veto on it. When I got it, I walked around dazed for a couple of days again. I eventually got in touch with an uncle, who didn't know I even existed, let alone anything about my birth. It was strange talking to him on the phone, asking him things about a person I didn't even know. I vaguely expected him to hang up in my face. He said she was living overseas and promised to get in touch with her and get back to me. I left him my phone number and that was that.

I waited five weeks, all the time wondering just where this woman must be living that it took so long for him to get in touch with her. In the end I rang back and asked apologetically if he'd found anything out. He said he had, and gave me her address, telling me she'd be happy to hear from me. He said he'd forgotten to ring back.

It was another five weeks before I was ready to sit down and write another letter. Phoning her was out of the question. I didn't have the nerve to go through with it. My letter was very businesslike. It said who I was and what I'd been doing in the last 20 years. It was a page and a half statement, basically saying "Here I am, now it's your move". The last thing I would have wanted is some huge emotional outpouring from a complete stranger, so I decided not to inflict that on her.

The reply was fairly prompt. It was about the same length as my letter. I noticed the spelling wasn’t very good. I also had a feeling she was using words that she wasn't used to, because some of her sentences were a bit awkward. It was sincere though, and that's what really mattered. She gave me her life story in brief, why I was adopted and finished off by saying she was proud that I was going to varsity and all that. It was the first positive thing I'd got out of the whole ordeal, and I was floating around on cloud nine for days afterwards.

We've written other letters since. When she sent me her photo, I was amazed at the family resemblance. She seems like a fairly ordinary married woman in her forties. Her first three questions about me were whether I had any girlfriends, what sports I played and whether I drove a car. Fairly mundane things really. I was hoping for someone a bit more out of the ordinary, but she seems a nice enough person.

I told my adopted mother about her the other day and immediately got bombarded with doubts, fears and insecurity. I found it all very hard to handle and felt I could have talked till I was blue in the face and I wouldn't have changed the way she felt. She's just going to have to come to terms with it as best as she can. I now see it all as a positive event. I now have a better idea of who I am and there's no more skeletons in the closet. My worst fears are gone, and although there's still some things I don't know about, they're fairly insignificant.

Diane

I decided early on not to abort. My father's Catholic, which has to be one of the main reasons. I was actually in the doctor's office and told her I was going to abort. She said "Fine, I'll make an appointment and we'll do it next Tuesday". And I thought, "Next Tuesday! You've got to be joking!" 'Next Tuesday' was a way of forcing me to accept what I was doing and I knew then I wouldn't go through with it.

He (the father) wanted me to have an abortion. He was feeling that he didn't want to have a child of his brought up by someone else. But at that stage he was just finishing his degree and couldn't take the child himself. There was no way we were going to live together and we certainly weren't in love with each other.

I went through a stage when I was going to change my mind about adoption, but after that probably not because at that stage the baby was kicking and becoming a real thing. I had a lot of time to think and you start to idealise. I went to Social Welfare. From the beginning the assumption was that I was just finding out about adoption. There's no commitment at all. It just consisted of a series of meetings about once a fortnight for the last three months.

Being pregnant for the first time is an amazing experience that you just can't describe, but the whole time I was pregnant I was never able to feel totally happy, because I wasn't supposed to be having this child. I wasn't going to keep it. Although my family was really supportive, it was like everyone pretended that I wasn't really pregnant. I'd be sitting there and the baby would be kicking but I wouldn't be able to go; "Ahh! It's kicking! It's kicking!" like most mothers do. I'd just have to sit there and pretend it wasn't happening.

I was in a hospital, filled with women who were thrilled to bits, and choosing names. I was in hospital for three weeks, and everyone would say; "And what are ya gonna call your baby?" and "Where's yer 'usband?" and "is this your first child?" And I'd have to say; "I'm not keeping this baby", and they'd go “Oh”.

I had a very hard pregnancy, physically and emotionally. There were no congratulation cards and everyone else was getting big bunches of flowers and presents for the baby. People were good to me though. They all brought me presents, but they were presents for me and not for my baby. I felt like they were consolation gifts. These were to make up for my baby and nothing was going to make up for my baby. As a woman, you can't help but think that giving away your baby is the most unnatural thing in the world to do, even if you can rationalise it.

I had the baby in Dunedin, and the father was also in Dunedin. He found it difficult. He was very involved in his work - he's a studious person. He's not the sort who talks about things very easily - a very quiet sort of male. The whole three weeks in Dunedin, he didn't come and see me. For four days his daughter was in Dunedin and he didn't want to see her. He doesn't want to see any photos.

Adoptions are pretty amazing things these days. It's really changed heaps. You cannot actually adopt a child until ten days after it's born. The doctors have time to decide if the child is alright; the mother time to get over the shock of birth. Until the ten days are up, you're still guardian of the child. My mother brought me and the baby back to my home town and the hospital there, and then I checked out. That night I was given five sets of portfolios of couples. There's something like one baby offered per 20 sets of parents. If I didn't like those I could choose another set. It had the parents' income, relations, school background, their attitudes towards children, ages, and what they looked like. Social Welfare has a tendency to match children up on physical characteristics and predicted mental ability: because I'm a university student and the father was a doctor, it was considered to be a fairly intelligent child. You still get that thing where you get a girl from a middle-class background and they want to put the child in a middle-class background. I suppose it's quite old-fashioned.

One of the main reasons I chose the ones I chose in the end was because they already had a child who was adopted, and for me it was really important that she had some other family. There was not a chance that there was going to be a muck-up. They had really good attitudes. Although the husband was a career man, he made every effort to get home at lunchtime if he could. They went out to a relative's farm in the country on as many weekends as they could. That's the thing that really impressed me. I had the option to see them last year: I said no.

It would make me a bit of an emotional wreck for a fair while. I would be meeting my daughter at age one and a half who would not know me from a bar of soap and might in fact not like me. She might cry when I picked her up. It would stir up too many memories.

My experience on the whole has been pretty happy, although obviously as time goes on, I find it easier to cope with. I'll admit I went through a stage quite a long time after I came back to Christchurch when I really thought I was going to have an emotional breakdown. When my world caved in months later I didn't feel I could go to Social Welfare. It was a year; a year later from when I'd found out I was pregnant. It was like there was a big hole inside of me that I didn't think was ever going to go away. Life had, suddenly, no meaning for me at all; I just wanted to run away. Luckily, I found someone whose wife's a counsellor and I had a session when I cried and talked. I left there feeling fine. She was great.

Adoption doesn't seem to be a good choice in the eyes of a lot to women. There's an attitude of "you got yourself into that situation: You made your bed; you lie in it." Out of adoption, there are a lot of good things to remember. Although it was sad, in my case it was an amazing thing. The miracle of life. And adoptions are a pretty good thing these days although I don't necessarily think it's the best solution or the only solution. I'm dying to see her, but not yet: When she's older, probably about 18. If at any stage she wants to see me and it's alright with the parents, then it's alright with me.

Funnily enough, I’ve got a great aunt, and when she found out I was pregnant, she wrote to mum. She's got an adopted daughter who is 45 or so now, and when she was 21 and at university, she fell pregnant and they whisked her away to the nuns in Wellington for six months! And this, in all seriousness, was what my great aunt suggested my mother do to me. Mum just keeled over laughing: God, can you imagine it. They'd have me up every morning praying to the Lord for forgiveness!

It just shows how far we've come in 20 years. Women are standing up and saying "We're not going to be treated like a piece of shit that's got to be hidden in the cupboard, just because we're pregnant."

It all boils down in the end that you've only got one life and you've got to make the best of what you can. That's what she'll have to do, what I have to do and what everyone has to do. If you make wrong decisions, that's just bad luck and you have to make the best of it.

I've often thought myself how she's going to feel.

Originally published in CANTA No. 20, 7 September 1987 pp. 12-14.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum September 1987.

On Your Bike!

"Road Safety? - Ho hum BORING" you all mutter as you reach to flip the page over. Your mind goes back to those dull lectures you used to get as kids in school from visiting traffic cops. BORING. You're a hip eighties student and you want the meaty issues, like AIDs, Nicaragua, and when the next drinking horn is going to be on ... Who cares about the road toll?

OK, it's rhetorical question time! Some sweeping statements to scare the living daylights out of you and get you thinking: Did you know, that despite all the hoopla over AIDS, you, as an 18-25 year-old are more likely to die in a head-on collision on our roads than from AIDS? Did you know that 15-25 year-olds have the highest death rate when it comes to road accidents? (39% of all road deaths were people in this age group in 1987.) Did you know a recent report gave Christchurch the distinction of being one of the worst towns in New Zealand for road accidents? Did you know the fatality rate for road accidents in New Zealand is double that of Great Britain? (20 per 1,000 as opposed to 10 per 1,000). That more New Zealanders have been killed and maimed in traffic accidents since World War II than have died at war? There's almost no end to the statistical odds and ends I could throw at you, but the main point is that every time you hop on your bike or get into your car and ride along the road, the potential for blood and gore-style disaster exists. The general public react with ritual horror at aircrashes like the Erebus incident when a couple of hundred people are killed at a time, but accept annual road toll statistics as a fact of life, something to be put up with, that won't ever go away. The point is though, that like so many ugly things in the world today, our roads can be safer to use if you do something about it.

No overall change in the situation will come unless enough individuals make the decision to drive more safely. Million-dollar Ministry of Transport advertising campaigns haven't worked, and nor will harsher penalties for dangerous drivers. Fines and prison sentences don't bring back the dead, and don't serve as a great deal of consolation to the surviving relatives of accident victims.

Rhetorical question time No. 2: What can I do to improve levels of road safety? Mainly very obvious things. For motorists, they are steps that will have been heard before - advice that sounds so damned obvious that a lot of drivers don't bother remembering it. Stuff like - keep your car road-worthy, wear a seatbelt when you drive, don't drive when you're sloshed, keep within speed limits, be very careful about overtaking other vehicles, indicate well before making any turns, keep a certain distance between you and the vehicle in front etc. etc. The sort of advice that makes most drivers think "What do you think I am, dumb or something?" Unforturntely, it's those dumb little things which get people hurt when they're not remembered, and when M.O.T. statistics give causes of accidents, they sound so banal you wonder how drivers could be so stupid - "overtaking", "head on collision (not overtaking)", "loss of control or ran off road", "vehicles crossing paths...". Every year in New Zealand over 700 people get killed as a result of the same old mistakes.

It's not only motorists who get themselves killed either, although they do have the distinction, unlike motorcyclists and cyclists, of killing large numbers of other people in collisions. A drunken motorist has a fair chance of killing a few other people as well as him/herself: a drunken cyclist or motorcyclist is a menace too, but is only going to get him/herself killed if there is a crash. In 1987, 131 motorcyclists died on the roads in New Zealand, as did 18 cyclists. The second figure sounds far from spectacular, but a death is a death, and even one of those statistics caused a lot of grief for someone. The rest of this spiel will be concerned with cycle safety, mainly because of the large number of cyclists at Canterbury University, and also because in theory, if not in practice, motorists and motorcyclists are meant to know what they're doing, having gained a licence and being required by law to keep their vehicles roadworthy. Cyclists don't have to pass any tests before they can ride on the road, and often their cycles are only roadworthy for as long as it takes them, or some essential part of their machine (like the chain), to fall off.

Probably the biggest favour any cyclist can do for him/herself is to go to the local library and check out a couple of books on bicycles. You'll get everything from information on cycle maintenance to road safety in far greater detail than can be discussed here. Also, check your library's 'HELP' directory for a list of local cycling clubs, although if you're just a casual commuter rather than a gung-ho mountain bike fanatic or a racing bike hoon. they may not have much of interest to offer to you.

Failing that, here's some more general advice. Buy a cycle helmet: it's a good investment, despite the steep $90-$100 plus price tags they have. Most cycling accident deaths occur as a result of head injuries. If you ride a ten-speed, your posture is such that the first part of your body that will hit an object or the ground in an accident is your head. Ten-speeds are designed so your head is hunched down well forward of the rest of your body in order to give better aerodynamics. It also turns your head into a wonderful battering ram when you collide with another object. Your forward-leaning posture also makes it quite likely you will be thrown headfirst over the handlebars and onto the road, should you lose control running over a pothole or debris in your way. Cycle helmets are expensive, ugly and uncomfortable to wear in hot weather, but these inconveniences are eminently preferable to having your brains scrambled on a piece of asphalt. By all accounts, cracking your skull open is not a very pleasant way to die, and cycle helmets can reduce your chances of that happening in a cycling accident by about 50%.

You will also need cycle lights, even if you only go to and from classes in daylight hours. It gets dark very early in midwinter and riding without lights at night is a way of life for the sort of people who would have enjoyed Russian Roulette had they lived a century ago. There are a great many motorists who are so short-sighted that they are incapable of avoiding other vehicles in collisions during daylight hours let alone at night time. The likelihood of them spotting an unlit cyclist on the roads at night are very low indeed. Also, one of the few fines the M.O.T. can place on cyclists is for riding without lights at night. In 1988, they made a point of looking out for cyclists breaking this particular law. So, to save yourself at minimum a $20-$50 fine and at worse the expense your relatives will have of purchasing you an oak coffin, you should buy yourself functional lights. The law requires a light for both front and rear. Finding decent lights is more difficult than it sounds.

Having unsuccessfully discarded at least half a dozen different brands as shoddy, inadequately designed junk, here's my advice. Vandalism and theft being what it is these days, you will need lights that can be removed from your bike when you leave it parked and locked unattended. Bike lights with dynamos are for this reason to be avoided. They also have the disadvantage that they only work while you are moving. When you stop at an intersection, the light flickers and dies and you have the same probability of being run over by a motorist who spotted you too late as a cyclist without any lights at all does. Of the battery-powered lights, Eveready make the most robust and reliable. They also provide better attachments for fitting to your bike than the other brands. Beware of tail light brackets with no horizontal support - the nut and bolt work loose and your light will smash into little pieces all over the road. For batteries, buy the rechargeable ones - they last years and work out a great deal cheaper than the normal variety. Another must for any cyclist is a lock. Bike thefts are a regular occurrence at varsity, and for all their alacrity at enforcing the campus parking regulations, our "Milkmen" (parking wardens) are rather ineffectual at preventing bike thefts. And finally, don't forget your shades - an essential accessory for any hip and groovy cyclist which also keeps insects, dust and other airborne particles out of your eyes (although unfortunately not out of your mouth!)

Originally published in the University of Canterbury Students’ Association 1989 Orientation Handbook pp.92-93.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

Make a Stand*

One of the most heartening aspects of the pastel-tone yuppie-ridden decade that the 1980s has become in New Zealand is the success of the anti-apartheid movement here. The uproar over the 1981 Springbok Tour proved to the Government and the NZ Rugby Football Union that playing sport with white South Africans just isn't worth the hassle. The cancellation of the 1985 tour as a result of public pressure, the closing down of the South African Embassy, the cutting of all diplomatic links with South Africa by the Labour Government, and the end of South African Airline flights to New Zealand all seemed to spell an end to links with South Africa. With the election of the Labour Government, the apathy and tacit support of the Muldoon Government for South African links became a thing of the past. Both David Lange and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Russell Marshall, have publicly expressed their dislike for what the latter described as a "terrorist state", run for the benefit of a white minority.

Despite the Labour Government's banning of South African agricultural imports in 1986 though, economic links between New Zealand and South Africa still remain. HART has been active in publicising and protesting the South African financial links of individual firms such as Rothmans, South British Insurance, Quills, Hughes and Cossar, Mair and Astley, and Brierly in recent years. On October 15th 1988, HART launched a nation-wide sanctions campaign against all firms in New Zealand still dealing with South Africa. Despite a limited trade ban by the Labour Government, NZ imports from South Africa amounted to $14,669,270 in 1987, with exports to South Africa totalling $17,689,671. New Zealand's big exporter to South Africa is the Government-owned (at time of writing) NZ Dairy Board, which sold $3.36 million worth of goods to South Africa in 1987. Amongst privately-owned firms, Fletcher Challenge Limited is one of the biggest offenders.

There are many objections made to the placing of economic sanctions on South Africa, usually made by those multi-national firms and governments which stand to gain from continued trading with one of the richest mineral-supplying nations in the world. Britain is a notable example, with Margaret Thatcher rejecting Commonwealth demands for total trade bans to be placed on South Africa. Concealing this profit motive are standard retorts such as "sanctions only hurt the blacks" or "sanctions never work because other nations always break them". The first argument is particularly ironic coming from those whose concern for the welfare of South Africa's oppressed black majority is far from evident at other times. A public opinion poll taken by the Community Association for Public Enquiry in 1986 indicated that around 75% of blacks in South Africa support continued economic sanctions on the white regime. Economic pressure against white firms from within South Africa is also being applied by the Federation of African Businesses and Consumer Services (FABCOS). FABCOS, a group of black business interests, are starting a 5.5 M Rand campaign around Pretoria in February 1989. Called "Keep the Rand Black", it aims at showing the level of dependence white firms have on black labour and consumers by boycotting them in favour of black businesses. Although economically, blacks are at the bottom of the pile in South Africa and the black consumer has little or no purchasing power in contrast with the average white, through sheer weight of numbers, such boycotts can be as effective as black labour strikes have proven to be. Not only does South Africa's black majority want trade embargoes in order to bring the South African Government to its senses and end the apartheid system through non-violent means, but the economic price of such embargoes is likely to cause far more concern to white business interests than to blacks. With 25% of all blacks in South Africa being unemployed, they have little concern for falling stock market values and a sliding foreign exchange rate. The white Government has already done its best to exclude blacks from the cash economy already, with black farmers living in the 'homelands' surviving through a barter-orientated subsistence economy.

If enough economic pressure can be brought to bear on white South African business concerns, it is in their best interest to urge the Government to change its apartheid laws in order that the economy can continue functioning. The cracks in South African financial stability are already showing, disproving those who say that economic sanctions do not work. Limited trade sanctions imposed by the Commonwealth, the USA, France and the total economic sanctions by Sweden, Norway and Denmark have spelt trouble for South African exporters and importers. Because of trade bans, (demand for goods + reduced availability = price rises: School Certificate Economics in action), shipping and container firms dealing with South Africa have raised their rental costs due to the delays and extra red tape sanctions cause. There has also been a loss in confidence in the South African economy amongst international investors. Since January 1988, the value of the Rand against the US dollar has fallen 27%. Gold and foreign currency levels are now the lowest South Africa has experienced since 1986. South Africa's Reserve Bank Governor, Gerhard de Kock, has reacted in shock at the country's falling import-cover ratio (the amount of cash held in reserve to cover import payments). It has now been reduced to a level sufficient only for two months. De Kock commented "three months import cover is serious, two months is a disaster".

Current sanctions have hit the South African economy hard in two particularly important areas - arms and oil. The international arms embargo against South Africa added US$ 2.1 billion in extra costs to South Africa's military budget and has forced South Africa to start its own uneconomical and costly arms industry. White power in South Africa rests largely on the fact that Government has the most modern armed forces in Africa. Higher equipment costs have made the maintenance of that power more difficult, and naval spending has had to be largely abandoned in favour of land forces. Oil, South Africa's most valued import, without which the whole regime would grind to a halt, has also proved much more expensive as a result of trade bans. Avoiding the oil embargo now costs South Africa US$2 billion every year. Amongst the multi-nationals still supplying South Africa is Shell Oil. Shell acts as official supplier to the South African Defence Forces and Police. They are the firm that had its logo plastered all over the UCSA building during a recent brass band festival here.

New Zealand has little to lose from a total trade ban on South Africa. None of the goods we purchase are unavailable elsewhere. NZ trade with South Africa comprises only 0.2% of our imports and exports. The introduction of a total trade ban by the Labour Government would serve to increase the pressure against the Thatcher Government by Commonwealth members wanting a total trade ban on South Africa. The current stalemate caused by Margaret Thatcher over the introduction of a total sanction policy would be broken. A remit passed at the 1988 Labour Party Conference in Dunedin - to have a total trade ban with South Africa by New Zealand - failed by only one vote. Its adoption as Labour Party policy would lead to New Zealand freeing itself of all links with the South African apartheid system, and would be a concrete step towards pressuring the South African Government to stop the insanity and suffering that current political system causes.*

(Including information care of HART.)

Originally published in the University of Canterbury Students Association 1989 Orientation Handbook pp. 94-95.

* This article was written a year before Nelson Mandela was released from prison and the collapse of the apartheid regime in the early 1990s.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

The Patterns of Chaos

The progress of science in the twentieth century has consisted of a series of attempts to get down to the bare basics of what makes the Universe tick. One of the great triumphs of twentieth century biology was the discovery of the structure of DNA, the basic building block of life. From the days of Rutherford and Niels Bohr early this century, particle physics has progressed from the discovery of the structure of atoms down into the confusing world of subatomic particles - neutrinos, quarks and a host of others - in an attempt to ascertain what the basic material of the Universe itself is comprised of.

Whether searching for the basic components of life or matter, science in the twentieth century has implied the triumph of reductionism. Based on the principles of Réné Descartes' Method, reductionism applies a mechanistic approach to the environment. In order to find out the workings of natural processes, you can treat the Universe in much the same way as you would a clock or a bicycle. By disassembling its pieces, examining them in isolation and then seeing how they fit back together again, you can obtain a closer understanding of the Universe's mysteries. Although the Universe is undoubtedly complex, it is assumed that by using this approach, you will eventually be able to build up a picture of how the world around you functions.

Reductionism, up to the twentieth century, has been widely considered a resounding success.

Humankind has applied the Method to the point where the world's physical environment has been affected: everything from the manipulation of genes through to altering the landscape for humans’ own ends, often with unexpected results on the ecosystem. In the last half of the twentieth century, the limitations of reductionism were beginning to be realised. Down on the subatomic level for example, particle physicists found their quest for the smallest, indivisible building block of the Universe to be leading them ever downwards into a multitude of increasingly smaller, unstable and short-lived particles. Millions of dollars have been spent on increasingly powerful machines called cyclotrons, which have circumferences of twenty kilometres or more, and are designed to smash atomic particles into one another at velocities approaching light speed so that smaller subatomic particles can be viewed amongst all the minute debris.

Particle physicists have succeeded in isolating particles so small and unstable that they exist for only a fraction of a second before recombining with other particles or dissolving into pure energy. Down beyond a certain point, they have found that their building blocks dissolve to a fuzzy point where the boundary between matter and pure energy is ill-defined. Here reductionism has proved a very expensive blind alley. How are you to reassemble the building blocks of the Universe when you've dissolved them into pure energy?

Whilst using reductionism in the search for easily isolated and analysable systems in the Universe, classical science has acted on the premise that nature is regular in its behaviour. Isaac Newton and his later followers like Laplace saw the Universe, from stars down to atoms, as a system that ran according to rigid laws. Nature was not, as the mystics of other ages had claimed, an unsolvable mystery, but could be analysed because it behaved according to regular, linear systems. This was evidenced in the laws of motion developed since the Renaissance - planets rotated regularly in graceful ellipses along orbital paths, and even a simple pendulum swinging back and forth showed a strict periodicity in its motions.

Unfortunately, the pendulum, along with other classical scientific models for motion, are not strictly correct. They are ideal examples that work only in a theoretical environment. Even the most stable planetary orbit is not totally regular - it is affected by the motion of the star it is rotating around, and by the gravitational pull of other planets and distant stars. In time, despite rotating in a vacuum, a planet will slow down, which also affects its motion. A pendulum does not swing regularly, but changes angle slightly with each swing. Its motion too exhibits a slight irregularity which, in classroom measurements over the last few centuries, has been attributed to "experimental error" and/or intangibles like friction and air currents, if it has been regarded at all.

In the real world, measurements of even the simplest motions can only be regarded as approximations - motions affected by a host of outside influences. Something as simple as a dripping tap, and a flag flapping in the breeze are systems influenced by a combination of forces too complicated for classical science to account for. Scientific teaching since Newton has always stressed the importance of simple, regular linear systems in its models; models which in the real world prove to be exceptions rather than the rule.

Not only does the Universe consist of irregular motions, but its geometry shows irregularity too. The pure lines of Euclidian shapes are more likely to be found in the computer-generated graphics of video games and films like Tron than in the natural world. There, perfect Euclidian geometrical forms do not exist: the Earth is not a perfect sphere; mountains, even volcanic calderas, are not well-formed cones, and there is no such thing as a truly flat plain. The shapes found in nature contain a complex irregularity that seems arbitrary or random. Even the simplest measurements of such shapes pose insoluble problems. Take the task of measuring the exact length of the South Island of New Zealand as an example. If you look up an encyclopaedia, it will give the length of the South Island's coastline as being X km. Any such figure is bound to be incorrect as the coastline's length is constantly changing. Rocks are eroded and tides wash in and out taking sand and silt with them. The coastline is not rigid; its boundaries are always in motion, a constant state of flux which prevents any measurements of its exact length. A mathematical model of a coastline can be found in a Koch curve (See Diagram 1.). Like our coastline, the Koch curve squeezes a line of infinite length into a small area, but on a far simpler level.

DIAGRAM 1: The Koch Curve

A simple model of a coastline. To construct a

Koch curve, begin with a triangle with sides of length 1. At the middle of each

side, add a new triangle one-third the size, and so on. The length of the

perimeter is 3 x 4 / 3 x 4 / 3 x 4 / 3 … and on into infinity.

However the area remains less than the area of a circle drawn around the original triangle - an infinitely long line surrounds a finite area.

Normal systems of measurement cannot account for the complexities of such irregular shapes, just as Newtonian physics falls short of accounting for the complex irregular movements of objects in the real world. Even your body shows a complex geometry on a level beyond that of Euclidian shapes. The body's blood vessels, from aortas to capillaries, squeeze a massive surface area into a limited volume, yet both your blood and vessels account for only 5% of your body. Your blood vessels are a three-dimensional version of the Koch curve that succeeds in intertwining a structure much more complex.

A new approach to dealing with the irregular, erratic and fuzzy side of the structure of the Universe began gaining acceptance in the 1970s. Scientists in a number of different fields, puzzled by the inability of traditional scientific analysis to account for non-linear systems, began searching for a new way of examining them. Pioneering work in examining irregularity, or chaos, began with a meteorologist named Edward Lorenz in the early 1960s.

Working on weather prediction research, he set up a simple computer simulator. Running a check on some results one day, he fed the same start figures through the computer again and was surprised to find that they produced slightly different fluctuations from the results he already had. Lorenz concluded that if his simple simulation of weather could produce different outcomes from the same initial start conditions, real weather conditions, depending on a larger number of influences, would also vary from the predicted norm of forecasts. Many low-level, unmeasured atmospheric changes could combine to cause weather patterns quite different from what was forecast.

Lorenz's weather simulator had produced random results from a simple deterministic model in the same manner that a given front passing through the atmosphere in a predictable manner could end up moving slower, faster, or in a different direction from what was predicted. He concluded that low-level forces in a simple system could produce complex results, often unexpected ones. In doing so, he cast doubt on the validity of long-range weather forecasting.

With complex systems, the scientific assumption was that they produced complex results. Air turbulence is a good example. The analysis of the turbulence caused by air currents hitting an airframe has always had to work on case-by-case simulations, with no two airframe designs producing exactly the same effects. Trying to conclude how a new supersonic jet fighter will perform on the basis of wind tunnel test data for a Cessna is clearly a waste of time. A more common case is smoke rising from a cigarette. At first it rises smoothly in a narrow column, then breaks into billowing clouds which break up and evaporate. To analyse even this example of turbulent air flow, reductionist methods have proved unfruitful. Even with the most powerful supercomputers, the turbulent flow of 1cm3 of cigarette smoke can't be accurately tracked for more than a few seconds. The complex shifting of smoke particles couldn't be broken down and reduced to parts simple enough to build up a broad generalised model. Using reductionist methodology, it took a huge amount of effort to build up an incomplete image of an incomplete area of turbulence, from which it was impossible to draw any generalised conclusions.

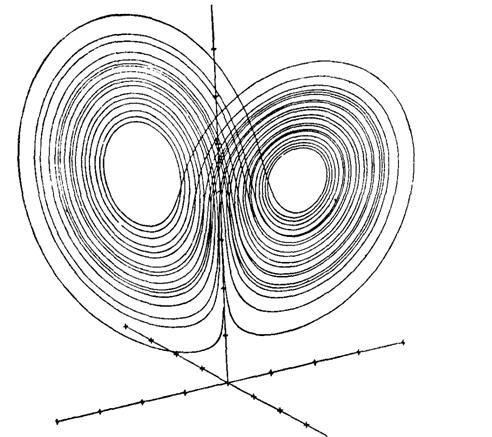

What resulted from Edward Lorenz's meteorological studies in 1963 was the image of this force that caused non-periodicity in airflow and other non-linear systems. Lorenz concluded that although no two columns of smoke are ever exactly the same, they followed similar patterns. Behind those patterns was a low-level, stable but non-periodic force or attractor (see Diagram 2.). This attractor, like the Koch curve, is an infinitely long line swirling around in a non-periodic loop of infinite area. It's the attractor's non-periodicity that causes the complex motion of a rising column of smoke. Subsequently it has been confirmed that all sorts of complex, irregular motions, from a swinging pendulum to the orbits of celestial bodies, depend on such attractors for their irregularity. Here was another shock to traditional scientific thinking: complex systems could produce simple behaviour. Previously, as with turbulence analysed in wind tunnels, it was assumed complex behaviour implied complex causes and could only be analysed, case-by-case as different systems would behave differently. Chaotic behaviour proved to have a system to its irregularity.

DIAGRAM 2: The Lorenz Attractor

The attractor reveals a fine structure hidden within a disorderly system.

Experts in this new approach to chaos hoped to turn back the tide of reductionism and use a new methodology to analyse complex, irregular systems according to their whole, rather than try and break them down into isolated and irrelevant little pieces, a mere fraction of the whole. A Los Alamos physicist, Michael Feigenbaum, concretised this approach to chaos in a mathematically-based universal theory, building on Lorenz's squiggly curve.

By the 1980s, chaos theory, was gaining acceptance amongst wider scientific circles. In looking at chaotic systems, Robert Shaw of Santa Cruz University defined chaos as the boundary between energy on a measurable level and on the microscale, but traditionally this was discounted as irrelevant. As Lorenz found out in his weather forecast research, the unmeasured energy on the microscale could affect the outcome of a system. Chaotic behaviour resulted from the boundary between the microscale and the macroscale, where unmeasurable forces interact with larger forces.

The chaotic behaviour of many systems in the Universe is now no longer quite the puzzle it once was. As the Universe decays according to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, it creates complex, fleeting and fragmentary structures that have in the past defied analysis. It is possible to look at the forms of this disorder now it has been realised that chaotic systems behave according to universal laws.

FURTHER READING:

James Gleick: Chaos: Making A New Science.

Douglas R. Hofstadter in Scientific American, November 1961.

Hao Bai-Lin (ed.): Chaos.

Predrag Cvitanovic (ed.): Universality in Chaos.

Originally published in CANTA No. 13, 12 June 1989 pp. 10-11.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

Days of Futures Passed

With the end of this century approaching, experts in 1990 are looking forward to what the 21st century will bring. Similar forecasts were being made around a century ago concerning what the 20th century would be like. Wayne McCallum examines some of the plausible and implausible futures projected in the late 19th century and asks if our predictions will look any better 100 years hence.

Most of the readers and writers of serious and spurious predictions about the future in the 19th century would have been unaware of it, but their views of the future were conditioned by their past and present. Laugh as you might at the ridiculous picture on the cover of CANTA of an air taxi half tangled in telegraph poles, the science fiction film sets and paintings which you might encounter and consider highly futuristic, will look equally outlandish and antiquated 100 years hence. Consider exercises in 1960s sci-fi like Thunderbirds. Three decades onwards, the futuristic designs of that TV series already look quaint. Projected futures date just as rapidly as the ages in which they were contrived. To understand why a past generation saw the future in a particular way, it's necessary to look at some of the popularly-held cultural assumptions of their era. To be aware of how much they hindered and distorted a past generation is to be aware of how much our own cultural assumptions affect our views of the future.

A Global Future

The view of the twentieth century discussed throughout this article will be a European-orientated one. In political, military and economic terms, European nations were at their peak in terms of global influence during the dosing decades of the 19th century. Not surprisingly, Western views of the future were the most widely recorded at that time.

The future of the world then seemed as if it was in the hands of Europe, a prospect few European writers at the time found particularly disagreeable. That future was never realised due to combinations of events the people of the 1890s couldn't have imagined, and perhaps wouldn't have wanted to imagine.

But in the 1890s it seemed largely inconceivable that the European empires would collapse. European empire building had been going on for centuries, in a piecemeal sort of way. It culminated in frenetic land grabs from the 1870s, particularly in Africa, which left European powers controlling around 90% of that continent, along with over half of Asia and most of the Pacific.

Despite the wars, cultural damage, economic disruption and political instability that this jostling by the European powers created globally, European expansionism was seen by its proponents in very positive terms. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany saw the European empire builders (himself included) as "the missionaries of human progress". European religion, technology, government and culture were perceived as a panacea for Oriental superstition and despotism. To supporters of colonialism, European empire-building seemed to be part of a great process of global unification, with modem Western values bringing about the downfall of tyranny and backwardness.

The empire builders foresaw a twentieth century dominated by the global might of European powers, with one leading nation playing a pre-eminent role. Which nation that would be depended entirely on the nationality of the person doing the speculating. For example, Frank Stockton, an American, portrayed the USA as the leading power of the future, in his 1889 book The Great War Syndicate. Through its implementation of rugged Yankee ingenuity and free market capitalism, Stockton felt the USA would be the world's pre-eminent power. That a non-European nation like Japan would show greater capitalistic vitality than the USA, and might even pose a military threat (as occurred in the 1940s), was inconceivable at the time due to racial prejudice, if not Japan's own economic backwardness and lack of resources at the time.

Similar chauvinism was displayed by other nationalities. Very few patriotic Englishmen would have held with Stockton's projection. Britannia was the one who ruled the waves at that point and long would she continue to do so. The toll of two world wars shattered that 19th century expectation. Victorians would have been shocked if they could have been told how little would remain of their empire by 1990.

19th century German imperialists would have been equally dismayed if they could have had the opportunity to see the state of their young nation in 1990. A fairly typical German view of the future was offered in Georg Ermann's Deutschland Im Jahre 2000 (1891). A linear protection based on then-current trends was used by Ermann to outline what state the world would be in by the beginning of the 21st century. Ermann believed Imperial Germany would be the dominant European power at the end of the 20th century, with larger European and overseas territories than it possessed in 1891; and with a much expanded economy. He couldn't have foreseen the political price of German expansionism though. The backlash from the other great powers in two World Wars left a partitioned Germany, with no overseas territories. Despite these drawbacks, on the threshold of German reunification in 1990; Germans look poised to further strengthen their already enviable economic achievements. But with no Kaiser leading the nation? For Ermann and other staunch 19th century German patriots, the idea would have been out of the question.

The European Imperial global condominium was never to happen. World War I shattered any vision of the European powers exerting benign global rule. By the 1920s, Western intellectuals were wondering whether European civilisation was just a thin veneer, beneath which uncivilised, violent emotions still lurked.

The twentieth century, as it happened, involved the quite rapid decline of European power. Very few forecasters of the 1890s predicted that non-European nations would assert their identities and reduce the level of European global influence. Rather than a diminished number of states united under Imperial rule, the 20th century resulted in the proliferation of newly independent states.

There were a few who did foresee this state of affairs though. A notable example is Charles Pearson, an Australian Minister of Education for the State of Victoria. In his National Life and Character: A Forecast (1894), he speculated on the rise of independent nations in what would later be called the “Third World”. He felt that China, at that time a large but militarily weak state, would become a great power.

Other forecasters clung to the myth of white global supremacy: William Delisle Hay's Three Hundred Years Hence (1881) for example. With a racist vision of white supremacy which surpassed the wildest imaginings of Adolf Hitler, Hay portrayed the rise of a white global order which decided on the systematic destruction of all groups of other ethnic origins. Fortunately, this was a vision which proved very wide of the mark, although perhaps less so back in the 1940s.

Science and Progress

Underlying the beliefs of writers in a European-dominated future, was the feeling that Europeans were succeeding because they had mastered the elements of physical, intellectual and material progress.

Europe had been clearly more technologically advanced than other areas of the world for at least three centuries. By the nineteenth century, it was becoming apparent that Europe’s rate of advancement was such that it was far surpassing the achievements of the rest of the world. The advent of steamships, and better guns of all shapes and sizes, were clear manifestations of this material success even the most conservative Europeans were forcibly aware of the fact that times were changing.

Surprisingly at the time, it was a work of biological science that was to emphasise the Western notion of progress. Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species (1859), had a great impact on the European mind. Commentators like Herbert Spencer and Ludwig Buchner picked up on Darwin's vision of a natural world were only the fittest and most adaptable creatures survived and applied it to human society. I.F. Clarke points out that from the 1860s, philosophies of Western progress merged with theories to produce "a general conviction of universal progress”.

Just as certain animals flourished because of their adaptation, so too, Western civilisation was assumed to be prospering because of its ability to adapt to change. Within Western societies, the rising industrial entrepreneurial class found a ready prescription for their way of life. Their struggle for economic market economies was now seen in terms of Darwin's "survival of the fittest". Crude as it is, this capitalist philosophy was still alive and well in Rogernomicsland in the 1980s.

White supremacists also found a simplistic explanation and a justification for their racism in Darwin's theories. Caucasians were the ascendant “race” which was gaining global domination due to its supposed natural superiority. It's interesting to anticipate how these 19th century European attitudes would have dealt with Japan's economic and technological rise in the 20th century. That other “races” might succeed in mastering technology was unthinkable at the time. For European writers enthralled with progressive notions who looked into the future, it was not only high-tech, but white.

Scientific Romance

But such philosophical nations were less important to most people who read about the future than questions like "what will people wear?", or "what will the new forms of transport be?". There was a host of popular writers who attempted to answer such questions from the 1860s onwards.

The broadening of these writers' imaginations is evidenced in the career of one of the earliest and most influential of them - Jules Verne. His success started with his first novel, Five In A Balloon. (1865). Within four years, he was much further into the realms of fantasy with From The Earth To The Moon. Verne introduced hundreds of thousands of readers to the future, although his future visions were a great deal less spectacular and methodical than those of later writers like H.G. Wells. Verne's adventures often centred on advanced fictional versions of-already available pieces of hardware. For example, the submarine Nautilus in 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, while large and capable of diving to great depths, was not that great an exercise of the imagination. Submarines already existed before the 1860s, when one was used in combat for the first time during the American Civil War.

In Verne's wake came hundreds of innovative and imitative writers the 1870s and 1880s. They provided visions of the future in cheap novels and popular journals, not only in France but also in Britain and the USA. Publications like the French La Science Illustrée, founded in 1887, featured engineering marvels of the future like transatlantic bridges and tunnels, huge passenger-carrying dirigibles, immense metropolises and so on. The future shown was bigger, better and faster, something still prevalent today in twentieth century visions of the future.

A good example of the sort of visions offered is to be found in the works of the French writer and illustrator, Albert Robida. Not altogether seriously, Robida drew dirigibles in aerial traffic jams, amazed citizens watching events in foreign lands through téléphonoscopes (what we would call “televisions”), and factory kitchens of the future which would pipe food directly into private homes. The architecture of his future cities was distinctly fin de siècle though, as were the clothes of their inhabitants. He offered a more complete vision of the future than Jules Verne, but it still had glaring omissions.

There were technological innovations made in the nineteenth century which Robida and other popular writers failed to foresee the consequences of. The standard form of air transport in late 19th century visions of the 20th century was the airship or dirigible, whereas the true form of mass air transport in the twentieth century turned out to be the fixed-wing aircraft, the first powered scale models of which were successfully flown in the 1850s. As for the dirigible, Robida, Verne and the rest couldn't have foreseen the Hindenberg disaster and the consequent aversion aerial travellers would display to airships from the 1930s onwards.

Nor did they foresee the means by which people would venture into outer space. Jules Verne's travellers to the Moon flew in a giant shell, fired from a cannon. H.G. Wells' First Men On The Moon (1901), travelled with the aid of anti-gravity. Six years before the publication of Wells' novel, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Russian mathematician, submitted his paper "The Exploration of Space With Reactive Devices" to the Russian Scientific Revue. The paper outlined the theory behind the construction of manned, solid-fuel rockets, the sort that would eventually take men to the Moon in 1969. The paper remained unpublished until 1903, doubtless due to its bizarre contents. Its true significance wasn't recognised within Russia until the 1920s.

The New Society

Just as predictions about what form future technologies would take were wide of the mark, so too were 19th century visions of what form 20th century society would take.

One uncertain matter was the role women would take in future society. The first stirrings of the women's rights movement in the 1880s spilled debate about sexual politics over into speculative fiction.

The aforementioned William Delisle Hay was as unfavourable to the women of the future as he was to non-Europeans. In addition to his racism, he held a misogynist view of the future. In Three Hundred Years Hence, he portrayed women as intellectually inferior. Being incapable of following the vaunted logical capacities of the male of the species, he assigned them the role of directors of domestic affairs.

Not all Victorian males were of a like mind. Sir Julius Vogel's Anno Domini 2000; or Women's Destiny, painted a quite different view of what women's lives would be like. In his society, women were the intellectuals, while men did all the physical labour.

Others preached sexual equality, for example E.B. Corbett in New Amazonia (1989). Such expectations have yet to be met within Western society.

There were those 19th century social thinkers who were not at all enamoured with a heavily industrialised future based on an ever-increasing rate of technological progress. G.K. Chesterton detested the notions held by scientific fantasy writers that more is better, speed rules and progress was the salvation of mankind. He ridiculed the advanced technologies offered by writers like H.G. Wells:

"Thus, for instance, there were Mr H.G. Wells and others, who thought that science would take charge of the future; and just as the motorcar was quicker than the coach , so some lovely thing would be quicker than the motorcar, and so on forever. And there arose from the ashes Dr Quilp, who said that a man could be sent on his machine so fast around the world that he could keep up a long chatty conversation in some old-world village by saying a word of a sentence each time he came around". (The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904))

William Morris, the English poet, displayed a similar dislike of industrial progress and what he saw as the “machine-life” it would create for people. His News From Nowhere (1890) showed a world that had abandoned industrial-based capitalism and had returned to small co-operative communities administered according to socialist principles. W.H. Hudson, likewise in The Crystal Age (1887), portrayed a rural future with a dwindled population that has returned to small communities, in harmony with nature, while the old cities lie in ruins.

Even more violent in their abandonment of technology were Samuel Butler's inhabitants of the anti-Darwinist utopia Erewhon (1874). Butler's imaginary Erewhonians banned machines because they feared that in the end those machines would develop to the point where they could outstrip the mental capacities of the Erewhonians and rule them.

But such views were very left of centre and untypical of the late 19th century. Overall, most speculative writers had no clear vision of the form future society would take and concentrated on future technology or obvious issues like women's rights.

The clearest visions of future society came from H.G. Wells and Charles Pearson. Wells, in his Anticipations (1901), picked up on some important facets of future society that most of the technophiles ignored or didn't highlight sufficiently. Wells foresaw the rising importance of mass education. He realised that advanced industrial societies would become increasingly dependent on international trade. And he saw English as the lingua franca of the 20th century, if only because of the millions already speaking it around the globe by 1901.