Short Pieces

by W.S. McCallum

Masterton Bound

W.S. McCallum

Back in the days before the railways were sold off to a foreign multinational, Petone railway station was a bustling commuter hub. Now the station building stands empty, its windows boarded up.

Under its rusting canopy, a couple of Samoan girls are waiting to catch the rail car into Wellington. They look and sound more American than Polynesian. Decked out in LA streetwear, they pass the time by loudly practicing their Ebonics. The shorter one has a baby’s dummy on a chain around her neck. It’s a fashion thing.

I am the only person on the platform opposite. My train, heading for Masterton, is a big diesel locomotive, hauling three antiquated carriages that rattle and clang as the engine driver slows them to a halt.

The passengers in the last carriage are a mix of townies and country folk, either going home for the weekend or on their way to visit relatives. They all chat happily, with the exception of two tangata whenua across the aisle. He looks like a Maori Jesus in denim. She, still in her teens, has braided hair and a Bob Marley tee-shirt.

They sit there wordlessly for a while, but the silence fails to last. He has a load to get off his chest:

“Three in the bloody morning and I have to come down to Wellington...”

Her voice is pained: “Ohh man, don’t start!”

Too late.

“And you just had to go and give that cop lip! As if I didn’t have enough problems.”

“You didn’t have to come down.” Her voice is as sullen as sullen can be.

“Half an hour getting the Holden started at three in the morning, plus an hour driving into Wellington, and now the bloody thing has packed up. Twenty-five dollars to get the train back to Masterton, and it’ll cost me even more time and money to get my wheels back on the road.”

He pauses for a while as the train pulls into Waterloo Interchange to pick up passengers, and waits until it is accelerating away before starting up again.

“It’s a bloody wonder you’ve got this far without ending up in hospital or prison. And those losers you hang out with! Jail’s the only place they’re goin’. If mum was alive she’d have a fit. All the sacrifices she made for us, and what do you go and do?”

In exasperation, he falls silent again. The silence lasts all the way up the Hutt Valley: a tense silence, barely holding back seething resentment and bitterness. Their faces say it all. And their stares; in opposite directions.

At Upper Hutt station, the last stop before the Rimutaka Range, a handful of passengers climb on board. From behind comes the sound of someone stowing his bag and settling into one of the worn leather seats. The new arrival, sight unseen behind me, greets him with the warmth of an old friend.

“Jeez man - haven’t seen you for years! How’s it going?”

He turns and stares in surprise. All traces of bitterness fall away from his voice: "Timoti! I thought you were over playin’ league in Sydney!”

“I’m back on hols. Been visiting some rels in the Hutt. Is that your sis there? Hi Rewa!”

A mumbled “hi” is all she manages.

“So how’s the old gang back in Masterton? What’s Hone up to these days?”

“Hone? Hone’s dead bro - he got run over. They never caught the bastard.”

“Yeah? So how are Mick and Jake then?”

“Prison.”

“Reckon I’m out of touch, eh?”

“You’re better off out of it all. Nothing ever gets better round our way.”

As the train enters the Rimutaka Tunnel, all three sit in silence, listening to the noise echo around the carriage.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum July 1999

Backpacker Transients

W.S. McCallum

Her voice is hesitant: "I can't stay for long - I have to get back to my room to pack. Early departure tomorrow."

He draws her into the room. "Just to talk, for a while."

She looks at him, at the bed, and at the empty room.

"We can watch some TV."

His suggestion is hollow, but is offered more to fill a gap, an empty moment, than for any real purpose. He unenthusiastically turns on the TV, momentarily fiddling with the aerial in order to eliminate the fuzzy reception but, upon failing, is more concerned with turning down the sound to a level conducive to conversation.

She is already sitting on the bed. Within the narrow confines of the room, there is nowhere else to sit. And just as well too, he thinks. A chair would have complicated the seduction process. He pulls off her shoes and clambers onto the bed, beckoning to her to recline and lie next to him.

She does so, but it is not the stuff of those intimate TV advertising moments. Instead, she is stiff and taut, her nerves clearly evident. An attempt at fumbling is swiftly rejected.

"I'm watching the telly."

He stares at her as she pretends to watch the TV - some programme about home renovations, of little interest to an English 20 year-old girl ("woman" would imply a level of maturity she has not attained) as it is to him. Her gaze eventually gravitates back to him. This time he kisses her.

It is not an expert kiss, but she smiles anyway.

He kisses her again, repeatedly, the way he has seen them doing it in the soaps back in São Paulo. He believes women like it like that.

Before long, he has progressed to unbuttoning her blouse. She instinctively withdraws.

"Nuno, you don't even know me!"

This too is a line from a soap opera, but she would be loathe to admit it.

He stares into her eyes, which are currently betraying that docile yet terrified look of a lamb about to be finished off with a stun gun prior to processing at the abattoir. He gazes deep into them and holds them while he pours all the emotion he can muster into saying "I love you. You are a beautiful woman."

These basic words are his Latino lover's equivalent of "Open Sesame". Hearing no denial or protest, he tells himself they have indeed opened the gate, and continues with the disrobing process. He muses that one day she will regale her friends back in England with tales of her hot South American lover, but just now the only heat being generated is his own. There is much kissing, fondling and so on. Breasts are exposed. Then comes the big step: the slow lowering of the fly on her jeans. He expects a cold Albion protest, but all she can manage is a worried "Be gentle..."

Once he too has his clothes off, there is room for momentary compassion. He gazes deeply (or so he believes) into her eyes once more.

"Are you alright?" he asks with the concern of a wolf about to take its first bite. He strokes her hair to offer reassurance.

She emits a now less reluctant "Yes".

"You have had boyfriends before?"

"Several."

It is a lie and he recognises it for what it is. She knows it to be a lie too, but she says it anyway.

"Are you..." he pauses, reaching for the right word in a language he has not mastered "...intact?"

At first she is not sure what he means, but having passed the Oxford entrance exams, she has the requisite brain power required to work out what he is alluding to.

"No."

It is an admission that there may not have been several, but there was at least one.

He doesn't look disappointed. In fact he is relieved. He has that Catholic guilt over the concept of deflowering a virgin, and an awareness of the potential for emotional misadventure when dealing with a total novice. To his mind, it is much better that there has been at least one other who has gone before him.

It is a mechanical act, not heightened either by her rigidity or his inability to satisfy a woman. A unilateral climax is reached in about five minutes, following which he gets up from the bed and opens a window to let some fresh air in, then wanders into the bathroom for a quick shower.

When he returns, she is fully clothed, sitting on the edge of the bed, waiting.

"I'd better go now. Early start tomorrow and all that."

"Yes." He hugs her and kisses her, unconvincingly. She is still as stiff as a board.

Just as she is walking out the door, he asks "What is your surname?"

She wonders if he wants it for a list, but spells it out for him anyway, and then is gone.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum May 2004

Sunset

W.S. McCallum

The flight touched down at Tontouta at 6pm local time. Still enough time. Time to get there. Time passed since last touchdown here amounts to a year. A year of greyness, chasing something that wasn't there, convincing myself regardless that if it was chased that bit more it night reveal itself and offer its rewards. Rewards ill-defined in the imagination, and unverified by actual sighting. Stifling pursuit of the unattainable, regarded with scorn, derision and taunts.

Spring heat warms away the malaise. The bus acts as a sauna, calming the fatigue of travel and relieving the weight of the past. Here those people mean nothing. Sweet strains of Tahitian music flow out over the intercom.

Thousands of kilometres now intervene as a barrier against them and their games. The thought that they are not so important is disturbed by the reflexion that if that was so, why are they still the subject of thought? Best to discard them as they wished to discard you. Sit back instead and watch the multiple shades of green rioting in the tropical heat.

Diesel fumes and rust, dust and nickel. Nouméa was busy clinging to reclaimed land at the edge of a flat lagoon, trying to look sophisticated and coming out Third World. Palms, banians and French signage filled in the gaps between the motley buildings. Kanak kids waving from the back of a Toyota pick-up, speeding past in the other lane, serve as welcome, although they themselves are outsiders to this artificial place.

The first French transported here thought the place was hell. They sat in confinement, watching the waters of the bay from the Ile Nou, wondering if they would ever get back to the cold winters of Paris, Lille or Rheims. No aircon and TF1 via satellite in those days. Hard labour and disease were the main releases from terminal boredom. End of history lesson.

Once the bags have been dropped off at the hotel, the way to the anse is open. Along footpaths cracked by banian roots, sidestepping the odd cockroach courageous enough to venture into the dim early evening light, trying to remember the rules of reverse traffic flows. Everyone is indoors, settling down for another Sunday evening at home, taking in a video, preparing dinner en famille or with guests, sinking beers and wine.

Hills, bends and crossings negotiated, the beach lies ahead. Past the shabby white weatherboards of the South Pacific Commission, filling up for the opening of an art exhibition, past the beachfront of the Banque Nationale de Paris, past the tourist strip with its overpriced bars, restaurants and curios, down to the water's edge.

The beach lies empty. The topless bathers and other sun worshippers have long gone. The sun is descending into the lagoon, its copper rays bending over the horizon, refracting through the few scattered clouds that have survived another day's evaporation in the Pacific heat. The Casino Royale, standing at the head of the bay is silhouetted in the dusk, a mere bump in the distance from here.

The change will come. I can make it happen.

And when it does it will be just like a refreshing plunge into cold water.

The sun is off to cast its light on Europe. Soon enough I will be joining it.

The lagoon water is salty. I spray the mouthful caught diving in and begin to laugh.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum July 1998

Words Come Back

W.S. McCallum

"Escape the sorrow of yesterday

love unheeded

tomorrow love unfulfilled

Love now"

I remember when you wrote those words. In school, as we used to call university. At the back of English Lit 101, looking down on an amphitheatre packed with two hundred first years, scribbling furiously, gleaning ideas from the beatific master at the podium.

You were as bored as me. Tripe about Wordsworth from a man who didn't have a single poetic reflex in his tired, unfit body. You took the course text and wrote your own poetry on it, just for me.

Others couldn't understand our happiness together. Young people can be just as cynical as their elders. We met days after enrolling and in the time that followed it just kept getting better and better. Dating turned to flatting turned to engagement then marriage. The whole trip. We neither of us placed great store in getting a piece of paper vouching for our love, but we wanted to make it legal, to stop the real world carving up half of what was left if one of us died. The law did not recognise de factos in those days.

I kept the book long after I lost the urge to reread Wordsworth. It got lost in the shuffle of shifting from one house to another over the years, both of us having abandoned our muse in the chase for money. It was not 'till years later that I realised it was gone. I felt a loss. Not for the book, but for those words.

There was a time later when I wanted to find it to fling them in your face, as evidence of what you had been and the treacherous, uncaring thing you had become. Your love proved not to be a statement of fidelity, but rather the hoisting of a flag of convenience. Love today, until something better comes along and then go your way. I searched high and low for that book, thinking maybe you had destroyed it or thrown it away.

No prop was needed for the screaming row we had. You slammed doors. I called you names, centering around infidelity and base morals. English has an ample supply of such words. It had an effect. You packed your backs and left.

I moved on, found someone else. You tend to, one way or another. I erased you from my life, if not from my memory.

And now here you are again. At a school jumble sale, buried in a Rinso box full of tatty paperbacks some parent wanted to dispose of. The book with your words.

"It's only a dollar - cheap really!"

The woman behind the counter meant well. She got no warning of the look of hate that froze her.

"You just keep it! Keep the bloody thing!"

© Wayne Stuart McCallum July 1998

Noel

Father Christmas arrived in a jetboat around dusk, his beard blown sideways by the slipstream.

Father Christmas straightened his artificial fuzz and jumped down onto the pier in a sprightly manner. For a man from the icebound North we had remarkably good sea legs. His sleigh was nowhere in evidence. The reindeer had been left at home. They didn't like tropical climes. On dry land and ready to swing into action, he contemplated the local substitute for his traditional sleigh. It was a weird contraption - a float of shaky construction piled high with boxes wrapped up to give the appearance of enormous presents. They had been glued and staple-gunned together to prevent them falling off while in motion. Hidden inside the float was Santa's driver. He already had the engine running. Santa knew not what vehicle the chassis had come from. Somehow he imagined it must have been a tank. One of the early ones that didn't steer too well. Its top speed of seven kilometres per hour served to reinforce the impression.

Standing on top of the jalopy shouting ho ho ho to the few members of the public who had bothered to come down to the waterfront, Father Christmas hoped the vehicle would not come to grief on a lamp post, as it had done last year. The road had been specially cleared for his passage. A paddy wagon in front and two motorcycle cops riding behind served as escort. The predesignated route took them past the American Monument, a point of worship for many who hoped that, just like Santa, the Americans might one day disembark again at the Baie de la Moselle, and bring back the heady days of wartime prosperity that had hit town back in '43. The mini procession turned with difficulty into the Avenue du Maréchal Foch, rolling past the second monument that the city had allowed to be erected to American culture. Diners munching hamburgers and french fries looked out past the twin golden arches as the man from the North Pole trundled past.

And trundle he did, painfully slowly, toward his destination, past the territorial museum and its coconut tree sentinels, shelter for wandering derelicts, past the Office of Post and Telecommunications, closed until the 26th, and then past the Bernheim Library, closed until January. It was a well-known fact that no one ever reads books over the Christmas holidays, so there was no need to be bothering them with a library service. Past the library stood the beginnings of a crowd that thickened as the paddy wagon led the way to Coconut Tree Square, or the Place des Cocotiers as the locals called it.

Parents and their children from all over town and beyond had come in to see the great man. The kids black and white alike, shouted in recognition, as the float and its passenger entered the square. "Father Christmas! Father Christmas!" The older kids and the parents weren't so excited. They didn't believe in fairy tales any more. For them it was an excuse to get out of the house and keep the littlies busy for an hour or two.

A blonde radio announcer in a Paris boutique number welcomed Father Christmas onto the podium and interviewed him about his travels with all the seriousness she would devote to a visiting Government Minister. Did it take a long time to come from the North Pole? Was he going to be busy tonight? Would he like the boys and girls to leave him a little something by the chimney as refreshment for when he called? The woman failed to ask him how he got down chimneys, or even which chimneys there were to get down. Modern houses in the tropics seldom need fireplaces. Presumably in this part of the world he jimmied open aluminium windows or ranch sliders instead, hoping no one would shop him to the gendarmes for breaking and entering.

Father Christmas told the boys and girls they would have to be very good or he wouldn't leave any presents. There was a moment's silence. To round off proceedings he officiated over a lolly scramble that became an undignified scuffle, saying his good-byes to a cluster of children with their tails in the air, grabbing anything that might be a lolly out from under each other.

Six armed municipal police escorted Father Christmas to the old town hall where, like Superman, he would transform back into a normal man and wander off to the café for a few mid-evening drinks.

Left behind to drive the jalopy back to its shed for another year, the driver cursed as the steering failed to respond to his guidance. He issued forth words Santa's elves would never have been allowed to use.

In a few hours it would be Christmas

Day in New Caledonia.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum July 1998

Beat City

Eddie dead since Tuesday. So said the disembodied voice down the telephone line. "Buried 'im in Melbourne, but I couldn't make it." A mental curtain dropped, blotting out further commentary while the news sank in. "Bloody good guitarist, was old Eddie. I remember seeing you blokes at the Stage Door. How long's it been since Russell ODed now? Nine years? Reckon that makes you the last one now..."

Later, in the still winter night, sitting alone in the living room, with the kids asleep and Mary too, half-forgotten dreams of other times return. Piece by piece, the memories are recollected, some important, some trivial, from a jumbled disorder reminiscent of a film studio cutting floor. The picture quality of the images leaves a lot to be desired. Seldom does the past return in technicolour with quadraphonic sound. True, some fragments manage to retain their original colour, only slightly blurred with age. Other pieces stand out in harsh black and white, cold and larger than life. And there are those damaged segments of the past which have been trampled on, swept away into the corners to be forgotten, or accidentally destroyed. Decades of neglect render them irretrievable, forever lost.

Time has erased large chunks of those distant experiences, leaving gaps that can be filled only partially by the posters, press clippings, photos and letters carefully retained from those days. All but a few dates have faded from memory, along with so many names, faces and places. That much of that past wasn't too sharply defined to begin with due to booze, drugs and the blur the world becomes out on the road, doesn't aid perfect recall either. Who was it who said, "If you can remember the sixties, you weren't really there?"

But the important parts will never fade. With the combination of damaged memories and the still extant physical remnants surviving time's vicious passage, a long dead world can be evoked and relived yet again.

Before Mary had come along, the one thing that gave life meaning was a good bass guitar. Such an assumption seemed laughable in the domesticity of life's middle years, but the old bass still took pride of place in the living room. Scuffed, scratched and dented from years of use, the Fender Bass VI leaned proudly against a Rockitt combo amp. The guitar and amp formed an incongruous pair; their sixties and eighties designs fundamentally mismatched. A style disaster. The modern amp seemed ill at ease alongside the black bass, with its crushed velvet style crimson scratch plate, screwed down over the sunburst finish. Chunky, single-coil pick-ups and an ornate tremolo arm rounded off the instrument's antique look.

The paths of musician and instrument had crossed in Sydney, early in 1968. It was a rare thing - love at first sight. She was the neglected toy of an uncaring fifteen year-old, acquired in the States by the kid's parents. Neither parents nor child were aware of what a rare creature they had on their hands. Not knowing what a six-string bass was, the lad had struggled in vain to master rhythm and lead techniques on it, then had abandoned the maltreated toy, despairing of ever getting the opportunity to be the next George Harrison. A joy to play, the Fender also constituted a real conversation piece amongst fellow musicians: '"That's no bass, it's got six strings!" was their usual reaction. Disbelief would then turn to intrigue as the bass's owner proved its worth, indulging in high-volume musical intercourse with like-minded instruments. The Fender performed just as it always had. Recently restrung, tuned, and plugged in, the bass sat patiently, waiting to be strapped to his shoulder yet again.

Less faithful were the amps and speakers of those bygone years. Some blame rested with their owner for this situation. One Hiwatt stack had met with a grisly death in Newcastle when the group had decided to do a Who and destroy all their equipment on-stage. Three amps self-destructed after repeated use at volumes their rudimentary circuitry wasn't designed to withstand. Two amps got stolen: "If I ever come across the bastard who flogged 'em, I'll bloody well..." Between '65 and '68, six amps had come and gone. The seventh, a Jansen, had survived into the early eighties, when it was sold off to buy the Rockitt. A sturdy amp was a rarity in the sixties. All the local and Asian product was crap, and the good stuff - Yank and Pommie imports - was expensive as a matter of course. How many hundreds of dollars they'd wasted replacing equipment constituted one of those many aspects of the past which the passage of time had erased. Perhaps it was better not to remember in this case. Not many musos had made a bundle in the sixties, but the same couldn't be said of music shop owners.

Little could be cherished more than the old Fender, with the possible exception of the five slices of black vinyl retrieved from the living room book shelf. Top shelf stuff, it took a chair, careful balance and some stretching to get them down without mishap. That shelf remained one of the few spots in the house which could be considered completely safe - out of reach from marauding kids, and a wife whose only irritating fault was an ingrained ability to cause distress by breaking things, or by carting them off to school fairs without warning.

The seven-inch discs were shrouded in black plastic. The black polymer implied nothing sinister; no funereal shroud or portent of evil this. Rather, it formed a shield against the elements, a preserver of life that prevented dust and corrosion from damaging its cherished contents. Within the black plastic, a product of the photographic industry, the slender vinyl slabs were individually cocooned in yet more plastic, this time the transparent, clip-seal variety. And within them, each record had its own plain paper jacket, mint-condition replacements for tatty originals which had seen better days. The singles had been carefully wrapped and sealed in 1975, when time had rolled on to the extent that the present tense of youth had shifted into the past. No diamond needle had scraped their surfaces since then - the songs stored in their grooves had been transferred to tape to prevent the inevitable wear that a stylus inflicts on vinyl.

Five singles. Not a bad output for a struggling kiwi beat group whose members never could make ends meet, and who, in the end, came to grief trying. Ten numbers, including seven originals. Quite an accomplishment in the days when kiwi music meant locals singing foreign songs. And the hit acts then were nothing to write home to the Old Country about. Who gives a hoot about the likes of Mr Lee Grant and Maria Dallas now? Pure dross. They wouldn't have recognised rock'n'roll if it barged along and kicked them in the shins. For all that, them and the rest of the middle-of-the-road hit fodder still got all the headlines in Playdate, and on the entertainment pages of the dailies. They monopolised all the local music shows, and hogged what little radio airplay was accorded to local acts. Given the NZBC's reactionary outlook on anything that vaguely resembled rock'n'roll, such a situation scarcely came as a surprise, but that realisation didn't render the status quo any easier to stomach. And when the squares look back on the sixties, who do they remember? Musical non-entities, and smiley presenters like Pete Sinclair, who didn't get to the top because they could play Bo Diddley or howl like the Stones, but because they knew the right people and because their managers could talk fast.

But kids with stars in their eyes fail to understand what a talentless rat-race show biz is. All that mattered for young hopefuls then was loud, dirty rock'n'roll, and dreams of becoming rich and famous. The visions of grandeur started when The Pretty Things roared through town in '65. Attacked in newspaper editorials, ridiculed by politicians, and loathed by stuffed shirts the length and breadth of New Zealand, they had delivered the RSA generation a good poke in the eye.

The Pretty Things probably didn't realise what a liberating force they represented for so many of their kiwi fans. Forget The Shadows, Forget The Beatles, even - God forgive us - The Rolling Stones: the Things had revealed what rock'n'roll was all about. Musical nirvana now implied outrageously long hair (shoulder length!), truly raucous guitar, and onstage behaviour verging on anarchy.

The Ugly Things were the group's bastard progeny. Admittedly, it was a derivative name, but what young band isn't derivative? The moniker also spelt commercial suicide, although no one realised it at the time. How likely was it that the NZBC would ever give any exposure to a gang of young hooligans with a handle like that?

Long hours spent learning bass, picking up songs and riffs, memorising lyrics, arguing and practising with the guys, organising gigs and playing in sweaty little venues till the wee hours... It's all gone except for the vinyl, the only surviving evidence of the group's musical worth. Ten humble sides with ''The Ugly Things'' printed on the label in big black block lettering.

Recording contracts never happened then unless a group had a live following first. Not like in the eighties, with all those synth wimps who got studio time because they wrote good computer programmes and could twiddle knobs on a 48-track mixer. The Ugly Things had to earn a reputation, starting at 21sts and school dances, playing pap, paying dues, before being allowed to let rip at the real venues. A residency at the Stage Door was the ultimate: the big time, or anyway, it was as big as you got in Christchurch. There was the Plainsman, the Invaders' old haunt, but that was passé. Better to be down in the cellar under Hereford Place, belting out grinding, sweaty noise among the black pillars, while the long-haired boys and girls grooved. The Uglys were always the support act, and never made top billing there. That privilege went to the Chants, who managed to leave all the other groups in Christchurch, let alone the Stage Door, choking in the dust when it came to live performances. Mike Rudd used to snarl into the mike and writhe around the floor. Trevor Courtenay, in between beating his drums, would swing from the rafters, a demented troglodytic simian. And Tim Piper slammed out wild noise with that guitar. Great blokes. If it wasn't for the Chants, The Ugly Things wouldn't have swung their first recording contract: two singles, released by Action Records. They weren't HMV, but it was better than nothing.

Off to Wellington! The big smoke. A chance to record and carve out a reputation on the other side of the Cook Strait. The trip's legacy - two singles, with sombre grey labels mounted on their black vinyl. ''Crazy For You'' was the first one Action released, in November -'66, followed by ''Please Please Please'' the following month. Some thought that James Brown's hit should have been left alone, but it wasn't a bad cover. Both singles stiffed. With no radio airplay (the good old NZBC strikes again) and lousy distribution, they failed to burn up the hit parade, so no one ever got to see The Ugly Things miming to their solid gold smashes on national TV. Poor old Pete Sinclair never knew what he missed.

Six weeks supporting Sounds Unlimited at The Place, then it was back to the garden city. Back to the same old routine - brickie by day and bass player by night, getting older and going nowhere. Dullsville USA. '66 turned to '67, and the Ugly Things were still stuck in Christchurch. Out in the world, everyone was digging the San Francisco scene, Sergeant Pepper's, Hendrix, turning on and dropping out. Dreams were voiced over beers in the early hours of morning; dreams of sailing off to California or England and taking the world by storm. Such stretches of the imagination couldn't be equalled by stretched bank accounts. Australia was a poor consolation prize but it would have to do, and if the Chants could make it over there, why not The Ugly Things?

Bright lights, big city. Sydney '68. Stuck in a support slot at a second-rate club called the Platerack. Getting on each other's nerves, crammed into a fleapit hotel room in King's Cross. Bumping into prostitutes in the hallway, with their $15 tricks in tow. Living off fish and chips and being hassled by servicemen and rednecks for your long hair.

"Get a haircut, ya poofter!" or "Waddahhyaa?" were the usual remarks. Australia was at war with the North Vietnamese. Long hair was considered a threat to the war effort and national identity. The big time. Bloody Sydney.

Bloody flower power too. White kiwi R'n'B didn't grab the punters any more. Out went the suits, leather jacket and Beatle boots, to be replaced onstage by jeans, loud paisley shirts, beads granny specks and a Buffalo Bill jacket. Mike, the group's newly acquired Aussie manager, pushed for a name change too; ''The Love Generation". "No bloody way mate, we keep the name we've got." There were limits.

The Aussies took to the new image, to everyone's surprise. So did the group eventually, writing silly cosmic lyrics and overindulging in extended freeform solos. Mike started swinging lots of bookings - varsity gigs, clubs, folkie hangouts, teenybopper discotheques. Groupies started hanging around. It was all happening. HMV in Australia released three singles. There was even talk of an LP, until the last of the singles failed to climb beyond number 49 in the charts. Still, there would be other opportunities for record deals, and with all the gigs happening, who had time for recording?

Life became a whirlwind. At last, some real money began rolling in. Enough to pay the bills, buy neat gear, and to partake of plenty of booze and dope. The latter helped deaden the grind of endless one-night stands. Drive all day. Set up at the venue. Gig till early morning. Collapse into bed in some crummy motel. Up at nine to drive all day again to the next booking. Repeat until exhausted.

Little wonder that everybody ended up hating each other. Fatigue weighed so heavily on the senses that the only conversational responses The Ugly Things could elicit from one another were grunts and mumblings. Bitter arguments became common among old friends. Such disputes could be provoked by the most ridiculous things - a misplaced packet of fags, or a bum note played at a soundcheck. Being loaded up to the eyeballs with pills didn't help the situation. For a couple of days you sped, behaving like a freaky hyperactive child, until you crashed, wandering around bearing more than a passing resemblance to some Haitian zombie. Inevitably, the music suffered as a result. Sometimes the guys were so screwed up they couldn't get out of bed. Mike could scream about the bills that had to be paid and "how are we ever going to show our faces in Melbourne again after that shambles last Friday?" till he became hoarse, but it didn't make any difference. The human body only withstands a certain amount of abuse before it gives up the ghost and demands time to recuperate.

It was on the way to Geelong. The seventeenth of February, 1969. A hot, sunny morning, with a clear, blue sky and not much traffic on the road. The atmosphere in the cramped Commer van felt tense, with everyone tired and irritable, wondering how long it could last and "where in Hell has all the money gone?" Mickey, probably more tired than the rest after a long night beating the skins, sat at the wheel, whistling something, putting everybody on edge with shrill notes. Mike was sitting in the navigator's seat, flicking through his diary, telling everyone they could have a couple of days off next week. Then Micky yelled out something obscene and the van went screeching off the road and into a telephone pole.

No seatbelts in those days. Mike and Mickey flew straight through the windscreen. Not a pleasant sight. In the back of the van, equipment, instruments and bodies all bounced around, collapsing in a muddied heap on top of each other. Apart from a few cuts and bruises, everyone in the back was okay. The ambulance carried Mike and Mickey off in stretchers, with sheets pulled over their faces. Later, someone concluded that the van's steering had broken down. It was Mike's fault. In between booking all those gigs, he hadn't kept the van's warrant of fitness up to date.

No one could see any point in continuing. Back to bricklaying, living in Melbourne for three years, before coming home. There have been other groups since The Ugly Things, and other gigs, but music's just a social thing now, a bit of a laugh in the weekend. That original fire has gone. All that remains are thoughts of what might have been but never was. The distractions of job and family have steered life off in a direction different from the one envisaged in the exuberance of youth, leaving behind that crashed van and broken dreams.

Originally published in Takahe No. 10, Summer 1992 pp. 11-13.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1992.

Big Pete Goes for a Spin

"NEVAH BEEN TA BORSTAL!! NEVAH BEEN TA BORSTAL!! NEVAH BEEN TA BORSTAL!!"

A sonic wall of pounding drums, slashing guitars and nasal punk whine spewed from the stereo's speakers like aural mucus. Fortified to the eyeballs with an afternoon substance session's worth of booze, dope and nitrous oxide, Big Pete and Little Pete pogoed vigorously and slurred to their hearts' content. Empty beer cans crunched beneath their boots and they periodically bounced off the living room furniture till the Proud Scum lurched to the end of their magnum opus. The sonic assault over, the two Petes likewise lurched back to the leather sofa and flopped into it. Big Pete belched. It was a big belch, as belches go. "Oorr! That's ace!"

"Yeah, effin' brill eh?"

"Y'know, every time I hear that one, I jus' wanna..."

"Yeah, know wocha mean. Wannanuvaone?" Little Pete waved an empty can and tossed it on to the Bremner shagpile carpet.

"Nah, nah Pete. Reckon I'd better be goin' soon..."

Little Pete rolled on to the floor and started groping around amongst the scattered nitrous tubes that had rolled under the sofa.

"Aww, c'mon. 'Ow 'bout some more nitrous?"

"Yeah, well since ya twisted me arm I won't say no." "Oh stuff it! We've run out!" Little Pete crawled back onto the sofa with some difficulty. It was the centrepiece of his parents' three-piece suite. His torn denim outfit contrasted nicely with the black leather upholstery. "Oi, there's still those beers over there."

"Nah, nah mate. I wanna save those ones. I'm goin' round Buzzy's place remember? Then I'll meecha at the Caledonian."

"Yeah, it'll be a good one. Youth For Christ are on tonight."

On the spur of the moment, the pair suddenly burst into song.

"DON'T WANNA BE A MOD!

DON'T WANNA BE A ROCKER!

I WANNA BE A

PUNK ROCKER!"

"Yeah!" Big Pete blinked, urging his bloodshot eyes to focus on his wristwatch. 6.20. "Ohh no! I've missed the bleedin' bus inna town. When's the next one, d'ya know?"

"Ten ta eight or sumfin'."

"I can't hang round that long. Buzzy'll be spectin' me."

"Hang on mate." Little Pete wobbled to his feet, then began pulling Big Pete into a vertical mode. "Come wif me - ya can borrow me mum's Mini. The olds are out for the night. Ya can bring 'er back tamorra eh?"

Little Pete helped steady his taller companion as he shakily tried to grasp the concept of both gravity and forward motion while they negotiated a path across the living room and into the adjacent kitchenette. Little Pete propped him up against the window frame while he rummaged through his mum's purse.

Big Pete rubbed his eyes and blinked at the early evening light, then gazed bleary-eyed down the hill. Mount Pleasant was a realtor's wet dream - an upper middle-class suburbia full of des. reses clinging to the hillside all the way down to the Estuary with its bracing sea air and seagulls.

Merivale looked almost mundane alongside this lot. Still, at least he'd cleared out of home there ages ago. Had a flat in Linwood. No bullshit in Linwood - real people, that's what Linwood had, not like la-de-da Merivale.

Little Pete prodded him back to his senses. "Look, 'ere's the keys. Get 'er back by noon and they’ll nevah know."

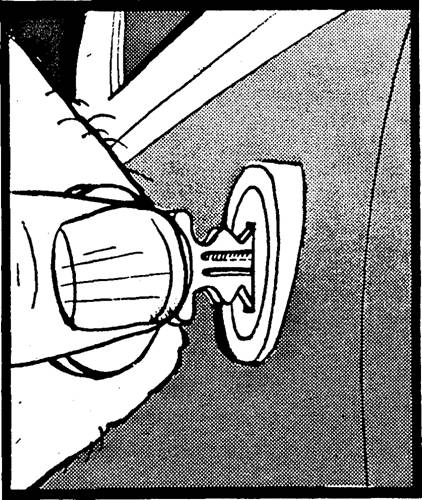

Big Pete's wobbly walk out to the split-level garage turned out to be one of the most arduous treks he'd ever completed, surpassed in difficulty only by the Herculean task of unlocking the car door with a key that refused to fit. Having sluggishly mastered the concept of "upside down" as opposed to "right way up", Big Pete then preceded to outdo himself by unravelling the intricacies of left and right as he twisted the key in its receptacle.

Once inside, he dumped the remnants of the six-pack in the passenger seat and emptied his jacket pocket of a cellophane bag's worth of dope lest it became damaged.

Starting the car and remembering to release the handbrake took a while longer to puzzle through and then he was off, much to the detriment of the silently suffering bushes lining the downhill driveway and the letterbox left wobbling in the Mini's wake.

Despite the quiet growl of the Mini's motor, Big Pete's tinnitus still rang irritatingly through his brain. Life had never been the same since the Gordons.

"Bitta music, that's what I need." A flick of a switch and the car radio crackled to life.

"AND NOW, REON MURTHA WITH THE RACING FROM ADDINGTON..."

"Oh shite!"

"...AND THEY'RE RAY- CING THIS TIME..."

"Bloody 3ZB - that's all I need!"

Even thinking about 3ZB made Big Pete feel nauseous. It epitomised everything he loathed in New Zealand; Mrs Popes, sewing machine ads and the latest quinella, beamed all over Christchurch with the express intent of further dulling the already feeble brains of bored housewives and their beer-bellied hubbies. It didn't bear thinking about when he was sober, let alone stoned.

"Gimme sumfin real for Christ's sake!"

"Yaaah!" Spinning the frequency tuner with one hand and steering with the other, Big Pete narrowly avoided tail-ending a parked sports car as he zoomed around a bend. It was fortunately only a momentary distraction and he was soon back to spinning the tuner past (yawn) Radio Avon and its other soundalike until he struck AM Mecca: 1422 Radio U!

"BUT THE MONEY'S NO GOOD! GET A GRIP ON YOURSELF!"

"Awlriiight! The Stranglers!" Big Pete loved the organ bit coz you could hum along with it "Dooo-dooo-dooo-dooo-dooooo! Dooo-dooo-dooo-dooo-dooooo!"

"Shiiit!"

The Mini's tyres lost a fair bit of rubber as Big Pete belatedly noticed the STOP sign at the bottom of the hill. Friday night rush-hour traffic formed a moving wall streaming continuously along Main Road. The sky was dimming as a prelude to nightfall.

A squeal of wheels and the Mini pushed its way into a fleeting gap in the flow. Big Pete tapped his foot to the Stranglers, blissfully unaware of the honking Mac truck behind him. Its driver was busy hurling expletives concerning Pete's dubious ancestry, cursing at having failed to reduce the Mini and its driver to tinned mincemeat under his wheels.

"Oh ya mongoloid Pete! No lights!" Once more the Mini lurched to one side as Big Pete moved one hand from the steering wheel to switch the headlights on. He momentarily found himself veering into oncoming traffic. A car's headlights' blinding beam struck his face.

"Fuuu..."

A quick swerve back into the left lane and Big Pete was on his way back into the land of the living. Once he got on to Linwood Ave there were no worries. The road ran as straight as a nail for miles. You'd not only have to be paralytic but blind into the bargain to run off the road along Linwood Ave.

"...EVERYTHING COUNTS IN LARGE AMOUNTS..."

"Oh no, not bleedin' Depechey Mode! Bloody student wallies! Can't play anything decent..." Big Pete flicked the radio off, heedless of the red Toyota station-wagon slowing down in front of him to make a right hand turn. KA-RUNCH!

Big Pete's Mini glanced off the Toyota's tail lights. Or to be more precise, Little Pete's mum's Mini that he'd lent to Big Pete did so. Big Pete couldn't tell the exact nature of the damage that had been done to the Mini, but decided that he wasn't about to stop and bother finding out. He kept moving. Stuff the insurance - it wasn't his car, so the less the other lot knew the better.

WAA-ooh WAA-ooh WAA-ooh WAA-OHH WAA-OOH!

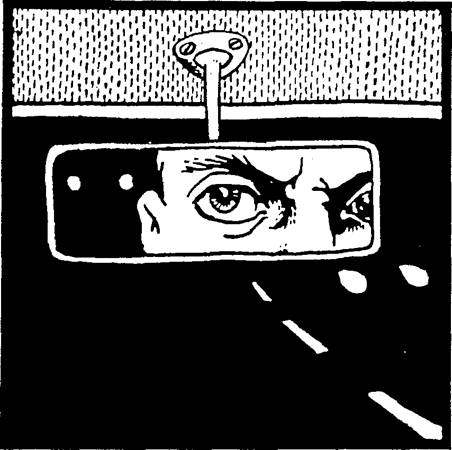

A black and white MOT vehicle materialised in the Mini's rear view mirror. "Oh my gawd - not the traffic cops! Not now! I can't handle this!"

Big Pete glanced down at the unfinished six-pack and the cellophane bag. If he tried dumping them out the window in his state, he was sure to end up wrapping the Mini around a lamp post. Suddenly his bladder started feeling as weak as his stomach did and guilty, psychotic babbling filled the car: "They've got me now - drunken driving, driving without a licence, causing a collision, and then there's the dope... AARG H! "

Big Pete began gasping for air, trying to calm himself down with steady deep breathing: "Calm yourself down Petey boy... control yourself... get a GRIP ON YOURSELF! They haven't got you yet ..."

Big Pete put his foot to the floorboards and zoomed past three cars blocking his lane.

"They won't catch ol' Petey boy. No way! Not me matey...'

Pete glanced up at the rear view mirror for reassurance. There were now two patrol cars hot on his tail.

"Chriiiist!! What'll I do now?!"

Linwood Ave turned into Avonside Drive and the traffic ahead slowed to a crawl along the lanes of the narrow road. Big Pete realised he was now cornered; caught in a slow-moving stream of traffic like a rat in a trap. There was only one way out: "Gotta overtake! Gotta!"

Big Pete swung the Mini into the other lane to overtake, only to find himself eyeballing the driver of a Bedford van bearing down on him. Staring death in the face was unnerving even in Big Pete's advanced state of intoxication. It was either halo and harp time or he could swerve one more lane to the right; only a flimsy wooden barrier, a brief grassy slope and a lot of water.

SCCREEECH! KEE-RACK! "ARRRRGGHH!!" RUMBLE RUMBLE SP-LASH!!!

Big Pete had done some weird things in his eighteen years on Earth, but driving Little Pete's mum's mint condition ochre Mini into the Avon River wasn't something he had ever contemplated even in his worst nightmares. And as he did for a moment contemplate the reality of life and the raw deal he was at that moment receiving from it, Big Pete briefly pondered over whether all this really was happening or whether he was just on a particularly bad trip and would soon stumble back into the real world.

The gurgling river water rising through the car floor and doors served to convince Pete that this unfortunate incident was indeed for real and if he didn't shift his arse promptly, in a few hours police frogmen would be fishing his bloated body from the Avon's waters. A torrent of water gushed through the door when he finally managed to push it open, and the Mini started sinking even faster. Big Pete pushed against the surge and forced himself clear.

He may have been stoned and sloshed moments before, but his dunking had brought him to his senses. Driving a car into a river tends to do that to you. Although Big Pete may now have suddenly become more alert, he was still far from being in a rational frame of mind. Any shred of sanity he had left was just as surely immersed in stoned paranoia as the Mini was in the waters of the Avon. Big Pete coughed and spluttered, clearing his throat of the muddy water he had inadvertently swallowed. Fortunately the Avon is shallow enough to deter all but the most fanatical suicide from drowning.

Pete's Doc Martens gave him firm footing on the river's silty bottom as he watched bubbles rise from the semi-submerged Mini. Along the riverbank all passing traffic had halted. A small group of motorists had even hopped out of their vehicles and gathered to watch the spectacle.

Big Pete realised he was still cornered. There was no turning back now. He sort of knew they'd nab him eventually, but he wanted some time to sober up before they breath-tested him. He started frantically wading across the far bank.

The two MOT officers standing with the motorists on the riverbank couldn't believe their eyes: "The silly bugger's trying to get away!" one gasped.

"Give it up mate! You don't stand a chance!" the other called out.

Big Pete ignored him. Things couldn't get any worse. He just wanted to get away. He clambered up the riverbank on the far side and started running, the soles of his Doc Martens squelching beneath his feet.

He disentangled a willow twig from his ear-ring and tossed it away. He now realised he actually wasn't too far away from Buzzy's place. Jump a few fences and he'd be there in no time.

Buzzy was just lighting up a big fat joint in the living room to die sound of "Sister Ray" when loud knocking at the front door downstairs broke through the music of the Velvet Underground. Buzzy's flatmates, Kris and Siobham, were slouched out on the old grey couch.

"Someone at the door," Kris muttered lethargically. She'd had a hard day down at the DSW arguing why her dole should be reinstated and felt disinclined to run around answering the door.

Buzzy didn't take the hint too well. "How about someone goes and sees who it is?"

Siobham tossed in her two cents worth. "We cooked dinner and did the dishes tonight. Your turn."

Buzzy was getting irritated now. "You just want first puff of my joint while I'm off answering the door. Well, smartypants, I'll just take it with me." He rose out of his tatty armchair, gave the joint a puff Noel Coward would have been proud of and then strolled haughtily out of the living room while Kris and Siobham exchanged a "that's what a Boys' High education does to you," glance.

Swinging the front door open, Buzzy damn near dropped his joint as well as his jaw at the sight of the leather-clad swamp monster who lurched through the portal.

"Ohh, Pete! You're drippin' all over the floor! ...What happened?!"

Big Pete's gaze zeroed in on Buzzy's joint. "Thanks Buzzy, just what I needed." He snatched the joint gingerly, just careful enough to avoid burning his fingers. He took a deep draw and exhaled before speaking in a shaky voice. "It's the cops Buzzy. They're after me! I totalled Little Pete's mum's Mini - smack into the bloody Avon!"

As if by magic, approaching sirens sounded in the street. Buzzy looked down at his dripping wet floor then outside into the half-darkness. There was a watery trail leading from the footpath right up to his doorstep.

"You bozo! What'd ya turn up here for? Now we'll all be done! Christ - I've got plants growing upstairs!" He stared in shock at the joint in Pete's hand, frantically snatched it back and then started running upstairs. Big Pete wobbled after him.

"Noo! Not you! Stay here - keep 'em busy while we flush all our stuff down the bog!" Buzzy pushed Big Pete back, knocking him off balance and leaving him in a tangled heap at the foot of the stairs. His body rolled up against the ajar front door and it slammed shut under the impact. Buzzy carried on regardless. There was no time for messing around now. He had to flush all the plants. And the bag of dope under his mattress. And what about the lot sitting on the living room table? And the smell - the whole room reeked of dope. He screamed out to Kris and Siobham: "Quiick!! Open the windows! Flush the dope! The cops are coming!!"

Big Pete groaned as he tried to pick himself up off the floor. Two helmeted silhouettes blocked out the light coming through the front door's frosted glass panes. One of them started pounding on the door.

"Open up - police!"

Big Pete was suddenly overwhelmed by the urge to chunder. A brown wave of sickly sludge gushed out of his mouth and onto the floor. Quite a reasonable thing to do under the circumstances.

Originally published in Cornucopia No. 10, Autumn 1989 pp. 14-16.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

Was a Soldier

A Ford Escort hooned by on the wet black tar seal as I stepped out into the street, with the hamburger warming my hand through the paper bag while the Coke can froze the other in the winter's night. I sidestepped a tidy little mound of dark brown gooey dogshit as I walked back to the car. It was late Friday night and everyone seemed to be of the same mind as me; a quick stop at the takeaway joint after the show on the way home. The place was crowded with hoons and the odd yuppie; the Cortina brigade intermingled with an occasional upmarket model. I had a fair wait, eyeing the wildlife as they fiddled with the joysticks on their "spacies". There were slot machines too... They sat there idly. The video freaks preferred blowing up electronic nasties to gambling. More gut-level satisfaction lay in blowing away the little nasties than stuffing coins in a slot and watching wheels go around.

He wouldn't have known much about Galacta, or much else in that sozzled state. Wrong age group anyway. Too old. He was staggering along the footpath accompanied by that glazed look that descends on the terminally pissed. He'd spotted me. I did my best to ignore him. It failed. His eyes settled on me and he lurched to intercept me. I would have crossed the road but my car was parked on this side. I braced myself for a late night conversation with a drunk old man. He stopped directly in front of me, just that fraction closer to me than a person would have normally stood. I stopped too, accepting the inevitable. I didn't think he looked violent. He was pop-eyed, losing what little hair was left peeping out from under the base of his splotchy old skull. The veins stuck out on his nose. He stank like a rhino house. "I was a soldier, I was..."

He was quite adamant; I didn't see any reason to disagree with his statement.

"Were you?" I responded flatly.

Rules for speaking with a drunk. Number one: Never disagree. He stamped his foot. The ends of his baggy old brown trousers sloshed in a small but relatively deep puddle. He reiterated;

"I was in the army."

He paused. He was waiting for a response. Say something dummy.

"Is that so?"

Rules for speaking to a drunk. Number two: Humour him.

"I was in the army I was." He pushed his lapel forward. His grubby RSA pin fixed to it.

Clearly a conversation that wasn't leading anywhere. I'm not sure what he wanted me to say anyway. It looked like he was getting frustrated, his pickled brain unable to move his lips to express what he was trying in vein to say. I moved to one side to get around him. People were watching.

"Yeah, well my hamburger's getting cold. I avoided looking him in the face. "I'll see you 'round" (when hell freezes over, I added subconsciously.) I moved to step past him. He reached out for me with a wrinkled hand. It brushed against my shoulder.

"I was in the army I was!" I walked quickly away. His voice trailed away behind me.

"You don't believe me! No-one..." The rest got drowned out by the roar of a passing Holden. I didn't look back.

"No-one listens. Don't wanta listen." Downward glance.

"My feet're wet." Moves feet. "Bloody feet 're wet, juss like me." Stumbles on. The neon sign of the takeaway flashes.

"All the bloody same, don't care." The sound fades to a mumble. A Maori kid stares through the foggy window of the takeaway, loses interest and turns back to watch his friend's game.

Good fighters the Maoris. By God, they had it bad. Too much time in the firing line.

"Jeez!" A momentary loss of balance as something slides underneath his left shoe. He staggers on. Bad business, Pete going like that. Him 'n' Jimmy too. Gone for good.

"Don't bloody care!" The exclamation winds him. He wheezes and coughs.

Didn't care back when Jimmy went either. Did himself in. Said it was an accident, his boy did. Jimmy? An accident!

"Hah! " Clears his throat and spits.

Bloody doctor he is. Wasn't too hard for him to cover up. Keep the family name clean.

"Family name!"

Family name my arse. Accidental death. Killed cleaning his rifle. Three years at the war 'n' he's too thick to clean a 303? He said he'd do it one day too, miserable old bastard. Gone six years. Still miss him.

A passer-by shoves past. He sways a bit, regains his balance and stumbles on.

And now Pete. Now Pete. Gone. He didn't want to die. Too young to die, he said. Too young by half. "I'll be here till I'm a hundred," he'd say. Said it that last time we met, on Saturday. Coughing his lungs out at the bloody races and saying “I'll be here 'till I'm a hundred" every five minutes. Couldn't afford a hospital. Bloody bureaucrats said he could wait like everyone else. He was still waiting round when he went. Bastards. All the same to them. Toss us on the scrap heap. What war. That's history, who cares? Bastards.

It was the same in the thirties... No job. Then forget it, yer not worth a toss. "Not worth a toss." Must have only started the war to get rid of the dole queues I reckon. Put 'em all in nice pine coffins an' clear 'em out of the way. Paddy, our gunner, he'd been out of work for Lord knows how long. Said the war was the best thing that'd ever happened to him. Me too, I'd just got out of the school. A real no hoper I was. Didn't help him much in the end. That 75 got him on the push to the Santerno. Shell blew the top off the Sherman's bloody turret. Took him and half of our CO with it. A right mess that lot was. Me, driving, I was lucky. Used to think I was goin' to be the first to get it but I was lucky. Just a loud bang and a few metal splinters. Moved out that hatch like my pants were on fire.

The Yanks called them Ronsons. "Lights up every time", just like in the ad. Sure enough. One spark and the tank went up like Guy Fawkes night. The rest of us got away alright though. Me. Pete and Jimmy.

Sounds of giggling. Three girls waiting for a bus.

One, a little blonde, whispers something to her friends. All three burst out laughing.

Stops. "Whasso funny?' He stares at them.

The little blonde steps forward and points. "You're pissed!'

The other two are in hysterics. Bright pastel tones. Too much make-up for so few years.

"Little tarts! Go home to yer mothers!" He turns and moves on, his muscles responding only slowly.

Bloody fourteen and out at this time of night. My dad would've tanned my hide, staying out this late at their age. And all that make-up. Bloody kids.

"You and your bloody war! I'm sick of it!" Marge's voice came back, the harshness still echoing in his head.

1951. He'd come home early from work, fed up with the tedium. Another afternoon off. He'd caught her packing her clothes into their tatty old suitcases. They had a row.

"I'm sick of it!" She decided not to back down this time; had flung it all in his face. "You come home pissed every bloody night of the week! Well you can shove it!"

She was a strong woman, Marge. That's why he married her. He saw her shopping once. Many years later. He was too ashamed to go and say hello. They never had kids.

"No-one cares... no-one..." His mutterings were drowned out by the passing traffic. The past, the past, the past. It kept coming back, like a scratched record that jumped. Again and again. He couldn't lift the needle. It went on and on. Nothing new happened. Just years of going through the motions.

The footpath had come to an end. His mind was elsewhere as he stepped off the curb. He didn't see the Vauxhall.

Originally published in Cornucopia No. 8, Spring 1988 pp. 8-9.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1988

Web site © Wayne Stuart McCallum 2003-2017

The picture copyrights of the various illustrations on this page are held by the respective artists. Names are provided in those instances where I could find them, but some are unsourced illustrations. If you are the originator of any of these illustrations and would like them removed please e-mail to notify.