South Pacific Politics

by W.S. McCallum © 1989-1992

1. French Nuclear Policy and the Path to the South Pacific

2. French Nuclear Testing at Moruroa

3. Island Undermined: Bougainville, 1989

4. Vanuatu 1990: Ten Years Beyond Pandemonium

5. Johnston Atoll 1990

6. National Does A Somersault on Nuclear Policy

7. The DORIS Affair

8. Uranium: Labor Runs into Trouble

9. Australian Uranium Mining Expansion On Hold?

1. French Nuclear Policy & the Path to the South Pacific

The French nuclear strike force or "force de frappe" is the third largest nuclear arsenal in the world. It currently [in 1989] consists of four components: 18 land-based intermediate range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) in silos; a fleet of six nuclear submarines each carrying 16 strategic missiles with multiple nuclear warheads; 62 Mirage 2000 bombers each equipped with an AN52 nuclear bomb; and ground troops equipped with truck-launched 'Pluton' tactical missiles. Alongside the nuclear arsenals of the two superpowers, with their tens of thousands of nuclear warheads, the French force de frappe is comparatively small but is easily capable of devastating cities and military installations in the Western Soviet Union. It also proved to be a complication at the Geneva arms talks during the 1980s. France has consistently refused to have its nuclear forces included in the NATO total in arms reduction talks, arguing that France has an independent nuclear defence policy (unlike the British) and would not tolerate the USA negotiating on its behalf. The USA, for its part, refused to have the French involved as a third party in what it saw as a bipartite matter between it and the Soviet Union.

France's President François Mitterrand was, in the mid 1980s, unwilling for France to be a party to European nuclear arms reductions anyway. He argued (and continued to do so in 1989) that France has the minimum force required for its national defence, whilst both the USA and USSR had excessive European nuclear arsenals. In 1981, the year of Mitterrand's election, NATO had 5,892 nuclear delivery systems deployed in Europe and the Warsaw Pact had 2,411. France on the other hand had less than 200. Until both parties reduced their European forces to a similar level, France could not enter into nuclear arms reductions without jeopardising its national security. Essentially, the same argument stands in 1989. Recent arms reductions undertaken by the superpowers in Europe are considered by Mitterrand (now in his second Presidential term) to be too small to be worthy of a French response.

In the past, France's desire for an independent nuclear defence has not always been seen favourably by the USA, which even today tends to view nuclear arms as an exclusively American prerogative. Their 1950s Cold War view of the world (still widespread in the 1980s) sees the globe consisting of two armed camps: the “free world” and the Reds. The USA has the role of defending the former by conventional and nuclear means, while the USSR runs the other side. This scheme has little room for upstart Frenchman (or NZers) who might not want to be part of the American nuclear umbrella. That the French might not trust the USA to act in the best interests of France in an emergency and prefer to conduct their own nuclear defence s'il vous plaît has been, for many American hawks, a typical piece of backward European parochialism mixed in with Gallic bloody-mindedness.

France’s continued pro-nuclear stance following the 1981 elections of Mitterrand and the French Socialist Party (PS) has also proved to be a source of bewilderment for the European Left as well as a source of confusion, considering anti-nuclear PS policy statements made in the 1970s. Mitterrand himself, in 1965, contested his first presidential election against Charles de Gaulle with an anti-nuclear policy, pledging to halt the introduction of the force de frappe which at that time hadn't entered service, as well as calling for the dissolution of both the Warsaw Pact and NATO. Such aims were a world away from Mitterrand's presidential statements in the 1980s, which gave support to the modernisation and extension of the force de frappe and spoke in favour of the European deployment of the US Pershing II and cruise missiles in order to protect Western Europe from the Soviet Union. Did this man really see himself as a Socialist? And compared to whom - Genghis Khan?

To understand France's policy of an independent nuclear deterrent, how a Socialist Government could ever reconcile itself with that policy in the 1980s, and its implications for the Pacific, it is necessary to turn to the birth of France's atomic programme in the 1950s. Contrary to popular belief, France's interest in developing atomic weapons predates de Gaulle's years as President. It was first officially expressed under the IVth Republic. Pierre Mendès France's Government decided in 1954 that research into the feasibility of an atomic programme should be undertaken. The same year saw a similar decision made on the subject of a French rocket programme.

Atomic weaponry seemed ideally suited to France's future defence needs. The French had fought two World Wars where conventional defence in the form of a large conscript army proved woefully inadequate at defending France's frontiers. World War I sent millions of young Frenchmen to early graves whilst the debacle of 1940 with the German conquest of France in a mere seven weeks was also an ugly memory. If the French army was unable to halt the numerically inferior German Wehrmacht in 1940, what hope was there of halting the Red hordes of Eastern Europe in the 1950s? Atomic weapons would provide France with the ultimate insurance against foreign aggression and would deter any enemy far better than conventional arms.

Going nuclear would also give France added prestige as an international power. Like the British in post-war years, many French leaders were disturbed by France's diminishing stature as a great power. The French economy (with US aid) was just recovering from World War II, France's colonial empire was collapsing while political divisions within France made the IVth Republic unstable, and there was France’s embarrassing withdrawal from the Suez invasion. Joining the elite nuclear club was one way of rescuing France from becoming a second-rate great power.

The decision to commence a French nuclear programme was made in 1958. Under the command of General Ailleret (known as the “father of the French atomic bomb”), nuclear testing began in the Sahara Desert, in Southern Algeria. Following Algerian independence, testing was halted and the programme shifted to French Polynesia in 1964. France's first generation of nuclear weapons entered service in 1967, and consisted of A-bombs designed to be carried by 62 Mirage IVA bombers. The planes had a range of 2,000 miles. It wasn't until 1971 that second-generation nuclear weapons entered service. These were nine IRBMs based in silos on the Plateau d'Albion. Both the bomber force and the IRBMs were vulnerable to pre-emptive strikes, and were a little out-of-date in comparison with the more advanced weapons being deployed by the USA and USSR by the 1970s.

It was the third component of France's nuclear force which was the most technologically advanced and flexible - the FOST (Force Océanique STratégique). This fleet of nuclear-armed submarines was to be capable of launching strategic nuclear missiles at sea, where they would be harder for the enemy to track, and would provide France with a second-strike capacity to enable retaliation after a foreign pre-emptive strike. The first of these submarines was launched in 1971.

The establishment of France's nuclear force from 1958 to 1971 occurred during Charles de Gaulle's years as President. Following the birth of the Vth Republic, de Gaulle worked steadily towards breaking France away from what he saw as the US hegemony over Western Europe and its NATO members. In 1959 he withdrew the French Mediterranean fleet from NATO command, followed by France's Atlantic fleet in 1963. In 1960 he had all US nuclear weapons and troops withdrawn from French soil, and in 1966 took the final step: France withdrew from NATO altogether. De Gaulle stated that France would henceforth pursue its own independent defence policy, free from US interference. When the nuclear bomber force entered service in 1967, General Ailleret declared that France's new defence strategy would be a “défense tous azimuts” (“defence from all sides”), as opposed to the solely eastern-orientated defence pursued by the members of the USA's anti-Soviet alliances.

It was during de Gaulle's years as President that Mitterrand emerged from the French Left as de Gaulle's biggest opposition opponent. Mitterrand's 1965 presidential election views on nuclear arms were traditional Socialist ones, calling for the nuclear programme to be dismantled. But later, in terms of nuclear policy as well as elsewhere, Mitterrand was to demonstrate a capacity to adopt a pragmatic approach that changed with shifting circumstances. By 1971, when the force de frappe was finally in service, Mitterrand had turned from embracing nuclear disarmament to a quite different stance. During the formation of the PS in 1971, he approved "the constitution of a minimal dissuasive force capable of menacing any eventual adversary" as party policy. Mitterrand now realised that the operational nuclear force presented any future Socialist Government with a powerful fait accompli involving millions of Francs and thousands of jobs. Even the basic question of how to dispose of all the radioactive nuclear warheads already in service, should they be dismantled, was a tricky problem. Thus in 1971, the PS pledged to halt future nuclear testing if elected but did not commit itself to dismantling the existing force de frappe.

In 1972, the PS joined the French Communist Party (PCF) in a Common Programme, an effort to unite the parties against the Right and gain more votes. The PCF pushed the PS into a hard-line stand against nuclear weapons. Their joint policy statement renounced nuclear arms "in any form whatsoever". When the two parties split in 1977, both revised this policy. On May 11 1977, Jean Kanapa, a spokesman for the PCF, declared that nuclear arms were France's "only real means of dissuasion". Taking what essentially amounted to a Gaullist position encased in Communist rhetoric, Kanapa stated that nuclear arms enabled France to stand up to any superpower "imperialistic nuclear blackmail". The PC made this volte face from nuclear disarmament partly to reduce its pro-Moscow image in the eyes of the French public.

The PC's turnaround left the PS clinging to a nuclear disarmament policy that neither Mitterrand nor his defence spokesman Charles Hernu agreed with. A new nuclear policy was formulated at the January 1978 Party Conference, several weeks before upcoming legislative elections. Charles Hernu pushed the PS towards an acceptance of the force de frappe. The FOST would be retained while land-based missiles and the Mirage bomber force would be phased out if the PS was elected. Then, rather than take any further decision itself, a PS Government would hold a referendum to let the French people decide if nuclear defence should be totally abandoned. These two resolutions were later to fall along the wayside in favour of a PS acceptance of the force de frappe as it stood. Hernu's January 1978 Convention on Defence also called for the modernisation of the force de frappe unless the superpowers made major nuclear arms reductions. This was a recommendation that was acted on after 1981. From 1978 till 1981, when Hernu was appointed Defence Minister in the newly-elected PS Government, PS members favouring disarmament found themselves increasingly marginalised. By 1981 Hernu and Mitterrand has accepted the Gaullist legacy of an independent French nuclear deterrent.

Prior to the 1981 elections, Mitterrand expressed concern over the USSR's deployment of SS20s in the European theatre and the US response of deploying Pershing IIs. In Point 8 of his pre-election policy agenda, the 110 Propositions for France, he called for both the USA and USSR to abandon the deployment of new Euromissiles. As President from 1981 though, Mitterrand became more concerned with the USSR's 151 SS20s, demanding their withdrawal whilst supporting the US's deployment of 108 Pershing IIs and 116 cruise missiles as a response from 1983. Following his election, Mitterrand became more concerned about what he perceived to be the military "supremacy of the USSR in Europe". Bilateral reductions of Euromissiles gave way to the desire that France and the NATO alliance should be able to defend themselves against this 'supremacy'. Considering that in 1981 NATO fielded 2,123,000 combat personnel against the Warsaw Pact's 1,669,000; and had 5,892 nuclear delivery systems opposing 2,411 Soviet ones (including the SS20s), this assertion is somewhat open to debate. Nonetheless, Mitterrand and Hernu placed the same importance on French nuclear defence as de Gaulle and General Ailleret had: it would deter any invader (presumably Soviet) from overwhelming the numerically inferior French army. By threatening that invader with the prospect of having its forces and country destroyed by French tactical and strategic nuclear weapons, it would avoid an invasion of France. May 1940 and Verdun would never happen again.

Faced with a lack of progress at Geneva and the Euromissile question in the early 1980's, Mitterrand's Government felt itself quite justified in continuing the French nuclear force's modernisation. In line with Gaullist thinking, Mitterrand had the tactical Pluton missiles that had entered service in 1974 brought under direct presidential control rather than leave them at the disposal of frontline officers. Port facilities for the FOST were extended and a new submarine called L’Inflexible was added to the force in 1985 at a time when the French navy was suffering spending cutbacks in its conventional fleet. Neutron bomb research also commenced and approval was given for 'Hades', a tactical nuclear missile equipped with a neutron warhead, to be put in service by 1992. The testing for the new warhead is currently [in 1989] taking place on the island of Moruroa, part of the Tuamotu Group in French Polynesia. This is the latest in a long line of tests that have been conducted on the site since 1966.

NEXT WEEK - FRENCH NUCLEAR TESTING IN THE PACIFIC: ITS ROLE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS [see below].

Originally published in CANTA No.2, 6 March 1989 pp. 14-15.

2. French Nuclear Testing at Moruroa

The first rumours that France might be planning a nuclear test site in French Polynesia reached John Teariki, the Polynesian deputy at the French National Assembly, in 1961. The French nuclear testing programme in Algeria was at that time jeopardised by the Algerian war of independence. Understandably, Teariki was alarmed at the rumours. His fellow deputy for New Caledonia sought a clarification of these rumours and was assured by Louis Jacquinot, de Gaulle's Minister of Overseas Territories, that no nuclear tests would ever be made by France in the Pacific.

That this was an empty promise was revealed in 1963, when President de Gaulle decided to set up a nuclear bomb site on the atoll of Moruroa (or "Mururoa" as the French mistakenly call it). The French Polynesian Assembly was outraged at the decision, with even the local Gaullist party calling for tests shifted to France instead. The French Polynesian Assembly was not reassured by glib French promises that any radioactivity from atmospheric tests would be short-lived, and that tests would only be conducted when the wind was blowing away from inhabited islands.

Governor Grimald informed the French Polynesian Assembly that defence matters were the sole concern of the French Government, and that the Assembly was exceeding its local powers in opposing the tests. The Democratic Party of the Tahitian Population (RDPT) was so incensed by this condescending attitude that it organised a drive to get the French Polynesian Assembly to vote for independence from France. President de Gaulle intervened and used his presidential powers to dissolve the RDPT without consulting the French Assembly.

Construction began later in 1963. 20,000 military personnel arrived to set up support bases on Tahiti, and occupied Moruroa. The agency running the tests, the Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) neither leased nor had title to Moruroa. As far as the French Polynesian Assembly was concerned, the CEA was squatting on Polynesian land.

By 1966, three years after the superpowers had agreed to halt atmospheric nuclear testing, France was ready to conduct its first explosion at the new Moruroa site. President de Gaulle himself was present for the occasion, which was to become rather a bother for him. When de Gaulle arrived at Moruroa, he was informed by his military men that the test would have to wait until the wind direction changed or the explosion would scatter radioactive fallout thousands of kilometres to the west over the Tuamotu, Cook, Samoa and Fiji islands. Two days later a very impatient President was still waiting for the wind to change. He informed the military brass that his workload in Paris was building up and he couldn't afford to wait any longer - the bomb was exploded. As President de Gaulle hurried back to Paris to resume his busy schedule, fallout scattered over inhabited islands as far away as Western Samoa, over 3,000 km to the west of Moruroa, where the New Zealand National Radiation Laboratory measured abnormal levels of radioactivity in local rainwater.

Atmospheric testing continued at Moruroa until 1974, despite the health hazards it posed to the region's inhabitants. Every mushroom cloud lifted radioactive dust up into the atmosphere, where it could be carried by winds for thousands of kilometres before falling on land or ocean. This fallout was easily capable of contaminating migratory fish swimming near Moruroa during tests. Fresh fish is an important part of the Polynesian diet and many contaminated fish ended up being sold in local markets. The French authorities annually purchased large quantities of fish from Papeete markets to test them for radioactivity, but the results were not made public, presumably so as not to frighten anyone.

Only sketchy data on radiation measurements made in French Polynesia were made available by France to the United Nations, and no real indication was ever given of the dangers posed to the region's inhabitants, or to what extent public health was affected by wind-blown fallout. Radiation measures were (and are) taken in French Polynesia solely by a military unit, the Joint Radiological Safety Service (SMSR), a unit with vested interests in testing. The French National Radiation Laboratory, a far better qualified and more objective organisation, was excluded from French Polynesia on the grounds of military secrecy.

The most dangerous ingredient in fallout is strontium-90, an isotope that takes 28 years to decay. Not only is it capable of contaminating fish, but also soil, and the rainwater that Polynesians drink (many islands have no other source of drinking water). Once it gets into soil, strontium-90 can be absorbed by plants, more importantly by the vegetables grown on nearby islands. When ingested, either through breathing or coming into physical contact with fallout, or eating and drinking contaminated food or water, strontium-90 can cause leukaemia and all sorts of cancers. As a result, the CEA warned islanders living near the tests that they should eat only tinned food and drink only well water, ignorant of the fact that these were not readily available to most islanders:

Those most in danger were the fifty inhabitants of Tureia, whose island lay well within the official danger zone, a fairly arbitrary area that in reality shifted with the winds. Tureians were only belatedly evacuated from their contaminated island in 1968, two years after tests began. Under a cloak of secrecy, the inhabitants were hidden in a military base on Tahiti for the duration of the 1968 tests and allowed to return after a "clean-up" by the military: this consisted of using hoses to wash fallout off the roofs of huts. It ended up being washed down into the soil of the huts' adjacent family garden plots.

Other islands outside the danger zone could also be victims of fallout if winds changed direction. Officially, tests were only to be conducted when winds blew to the east, but in practise winds were difficult to predict and changed direction all too frequently. In 1966, when atmospheric tests commenced, there was very little meteorological information available on French Polynesia, for the reason that the meteorological office (which was not set up until 1932) had burnt down in 1948, along with all its records. Military weather forecasts therefore consisted largely of educated guesses.

By 1972, international opposition to the biological dangers posed by French atmospheric testing in the Pacific had spread to over 100 United Nations members. Amongst those most prominent were Australia and New Zealand, who petitioned the International Court of Justice. Norman Kirk's decision to send naval vessels to Moruroa to monitor tests focused international attention, as did the publicity surrounding Peru's discovery of contaminated tuna in South American coastal waters, over 5,000 km away from Moruroa. That year, President Pompidou announced France's tests would be shifted underground. International concern over the safety of French tests died down once underground explosions started in 1975. Underground testing raised a whole new series of safety questions though. Haroun Tazieff, a French vulcanologist, called in to assess the suitability of underground testing in 1975, warned that the brittle, porous rock found on islands like Moruroa is susceptible to fracturing under pressure, which could result in radioactivity from underground blasts leaking out into the sea. This was the main reason why the US shifted its underground nuclear tests from the Pacific to Nevada in the 1950s.

Moruroa's main problem concerning underground testing is its smallness. American geologists have found that a 10 kilotonne bomb exploded underground hollows out a 20 m wide, 90 m deep cavity and fractures rock within a 300 m diameter. A 150 kilotonne bomb creates a 55 m wide, 220 m deep cavity and fractures rock within a 300 m diameter. French officials stated that at the depth at which explosions under Moruroa are conducted, the surrounding rock was only 100 to 300 m thick. Until 1978, underground explosions were conducted too close to the atoll's outer wall. On 24th November 1977, the inevitable happened: after a 150kt explosion, a tidal wave washed over the atoll. The only possible cause for this freak wave was that an underwater chunk of the atoll had been blown away by the explosion. The CEA, not having the necessary diving equipment available at the time, had no way of checking for a leak. This mishap prompted a shift of all explosions to the middle of the atoll of Moruroa, but this didn't prevent further accidents. On 6th July 1979, a warhead detonation in a sealed concrete bunker on the atoll's surface was carried out. Usually these bunkers are left sealed afterwards, but as an economy measure it was decided to decontaminate and reuse this particular bunker. During the clean-up operation inside the bunker, a spark from an electrical drill set off an explosion of radioactive gas. The bunker's doors were blasted open, two technicians were killed and four more were injured. The radioactive gas leaked into the atmosphere.

A second accident occurred soon after on 25 July 1979. A bomb being lowered down a shaft prior to detonation got stuck half way down. Not overly worried by this, personnel detonated the bomb anyway, heedless of the danger posed by detonating a bomb so close to the surface where the surrounding rock was thinner. Three hours later, a chunk of Moruroa's outer wall fell out. A tidal wave washed over the southern part of the atoll, injuring four workers. Asked what could have caused the wave, the Programme's Director, General Dubot, declared "I haven't the slightest idea".

Worse things were to be revealed by Libération, a French daily, on 6 November 1981. The north coast of Moruroa had been deliberately contaminated by the release of plutonium in order to test clean-up procedures. Several kilogrammes of plutonium had spilt into the atoll. To trap this, tar was dumped onto it. It wasn't deemed necessary to clean up the resultant radioactive tar. On 11 March 1981, a hurricane-force cyclone hit Moruroa. The cyclone sloshed tar all over the atoll and also washed away a 30,000 square metre dump of radioactive waste. The dump's irradiated scrap metal, wood, old clothes and plastic bags were washed around the lagoon. Some of this debris and some of the tar were washed out to sea through a natural four-kilometre gap that exists in the atoll wall.

The radioactive rubbish and tar scattered around the atoll was never effectively cleaned up by personnel on Moruroa. What remained of it vanished forever, washed out into the Pacific, when four cyclones hit Moruroa between January and May 1983. Belatedly, some months later, 450 million Francs were spent erecting a concrete wall on the sea and lagoon side of the atoll. No attempt was made to seal up the four kilometre gap that allows sea water to wash in and out of the atoll. it was a case not of shutting, but of half-closing the gate after the bull had bolted. As a protection against cyclones, this sea wall was of dubious value.

1981 was the year that France witnessed the election of the Fifth Republic's first Socialist Government. François Mitterrand, the new President, and his Defence Minister, Charles Hernu, were in favour of continued testing, viewing it as necessary for the modernisation of the French nuclear strike force, so it was business as usual for Moruroa. On 1 August 1981, Hernu was present for the explosion of France's first neutron bomb, the first of many such tests that continued until 1988.

Few outside observers have been permitted to conduct surveys at Moruroa. The team of doctors who produced the Atkinson Report in 1984 constituted a rare exception. Unfortunately the team only spent five days on Moruroa, where they were not permitted to take lagoon samples, or visit the atoll's contaminated north coast. The only samples they had time to take were from the surface of the ocean outside the atoll. As the last nuclear test had been made three months prior to their visit, the likelihood of them finding any radioactivity in the water that hadn't long since been washed away by the current was very slim. On 10 July 1984, Hernu claimed the Atkinson Report's findings justified French claims that the tests posed no danger to Polynesians. The Report's lack of conclusive evidence merely continued existing doubts.

Jacques Cousteau also visited Moruroa in 1987. Unlike the Atkinson team, his group had diving equipment. He later reported that Moruroa's geological state was "chaotic", with the lagoon in an accelerated state of ageing. Cousteau's divers found the atoll's underwater slopes lined with faults large enough for a shark to enter, although they had no way of finding out how far into the atoll's core they ran. It is reasonable to assume that after over 100 underground explosions, Moruroa is now riddled with cracks and cavities and that radiation has had the opportunity to leak out into the lagoon, then through the four kilometre gap in the atoll and out to sea. Personnel have not been permitted to swim in the lagoon for years. Drilling shafts for new bomb explosions has become difficult too due to the number of cavities already under the surface, left over from past explosions. In 1987, a test bore hit a cavity left from a past test and radioactivity leaked out to the surface.

Despite Moruroa's shaky safety record, unpredictable weather and its cracked rock and multiple cavities, in 1988 President Mitterrand reaffirmed France's commitment to continued tests there. In 1975, the vulcanologist Haroun Tazieff recommended that a test site in France's mountainous Massif Central would be safer than pursuing underground testing on a small Pacific atoll. Any shift of France's nuclear tests to a place so close to home might cause a backlash from the French electorate, something that the current PS Government, with its marginal control over the French Assembly, is reluctant to risk. It is considered better that the explosions should continue under a fractured, leaky atoll half a world away from France, where they are both out of sight and out of mind.

Sources:

Christchurch Press

Christchurch Star

Danielsson & Danielsson: Poisoned Reign (Penguin Books).

Originally published in CANTA No.3, 13 March 1989 pp. 6-7.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

3. Island Undermined: Bougainville, 1989

The results of a recent informal survey point to the conclusion that close to 100% of New Zealanders wouldn't know the island of Bougainville from a hole in the ground. Coincidentally, it's precisely because of a very large hole in the ground approximately 2.5 km long, 1.5 km wide and 64 m deep that Bougainville, for the first time since New Zealand troops were stationed there in World War II, has crept back into the periphery of New Zealand's Eurocentric media.

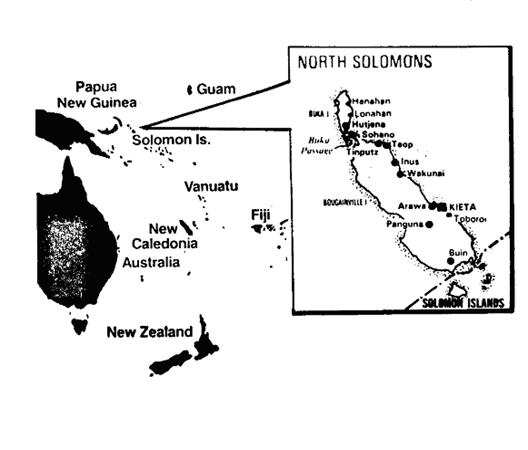

Bougainville is the largest, and one of the northernmost islands in the Solomon chain. It's about 180 km long, 50 km wide and has a surface area of 10,000 km. Although Bougainville is a province of Papua New Guinea (PNG), culturally its inhabitants have closer ties with the Solomon Islanders than with the mainlanders of PNG. The Bougainvilleans' aspirations for independence have led to conflict in the past, most notably at the time of PNG's independence in 1975, when Bougainvillean secessionists declared a Republic of Bougainville and PNG's leaders faced their first national crisis. Their response was to send police and army units in to quell any discontent.

The PNG Government's main concern then was for the continued well-being of its future economic growth, the centrepiece of which was Bougainville's Panguna copper mine. Initiated in 1964 when PNG was still under the administration of Australia, the Panguna mine has since developed into a major earner for PNG. Over recent years, an average of 200,000 tonnes of rock has been mined every day in order to extract copper from estimated reserves of over 800 million tonnes. The mine, run by Bougainville Copper Limited (BCL), produces not only copper (68% of its output), but also gold (30%) and silver (2%). These ores have comprised 44% of PNG's exports since 1974, and the mining operation generates 17% of the Government's total revenue, equalling one billion kina every year (US $1=K0.90). The greater part of BCL's profits go to Conzinc Riotinto Australia (CRA), which owns 53% of the company. Foreign public shareholders own 27.3% of BCL, while the PNG Government controls 19%.

Those receiving a less conspicuous cut of the mine's profits are local Bougainvillean landowners who have complained of ill-treatment since 1964, when the first Australian colonial administrator visited Panguna to purchase land. There were no negotiations and local landowners were simply informed that they would get nothing. They responded by laying themselves in front of bulldozers when work on the mine began. Under the PNG Government, the Panguna landowners were paid K17 million in mining royalties as compensation for the loss of land, and environmental damage. They receive 5% of mining royalties and claim that this isn't enough as compensation for the loss of their hunting grounds, and environmental damage caused by tailings and pollution to the nearby Jaba River. In April 1988 the landowners, with the support of local government and the Melanesian Alliance Party led by Father John Momis, lodged a K10 billion compensation claim, which was greeted with bewilderment and some amusement by the PNG Government and BCL. Very few governments outside PNG have that much money available to give to pressure groups, let alone the PNG Government. The claim was ignored.

Both BCL and the PNG Government were forced out of their complacency in November 1988 when a group led by former BCL surveyor, Francis Ona, started a guerrilla campaign against the mining operation. On November 22, BCL security guards were held at gunpoint while 228 sticks of dynamite, detonators and fuses were stolen from a storage shed. Two days later they were used to blow up an administration block, a helicopter and worker accommodation. This and other acts of sabotage caused K700,000 worth of damage. This time the PNG Government was forced to react.

Their response was the despatch of 200 police to Bougainville, led by Police Commissioner Paul Tohian. He ordered his men to shoot any "terrorists" if need be. On December 1, the saboteurs stole more explosives from a limestone quarry at Arawa, and used them the following day to blow a power pylon off the side of a cliff. The result was a blackout at Panguna and mining operations halted while attempts were made to reconnect the power. These attempts failed when a second pylon was blown up. On December 7, a maintenance building was also destroyed, resulting in another K350,000 worth of damage.

By December 8, PNG Prime Minister Rabbie Namaliu was threatening to send in PNG's Defence Force unless Ona's men negotiated. Prior to that, a Government delegation sent to Bougainville to negotiate had been ignored. Ona wasn't prepared to come out of the bush with police around. This new threat made him reconsider and on December 8 the destruction halted. On December 12, the saboteurs surrendered some explosives as a goodwill gesture. Francis Ona's demands were for a greater share of the mine's profits, shared more equitably amongst local inhabitants. Ona, a university graduate, and other discontented young men from the area, saw themselves cut off from their land, not only by the mineral exploitation of BCL, but by the matrilineal nature of land ownership and inheritance amongst their people. Royalties and benefits from the mine went to matrilineal title holders, usually conservative elders, who were not always interested in following the financial advice of their educated sons, grandsons and nephews. Family feuds and violence were a result as young folk accused their elders of greed and ignorance, while the elders accused their offspring of stirring and not knowing their place. Ona's closest land-owning relative, his uncle Matthew Kove, is now believed to be dead after being kidnapped by Ona's men.

Ona wanted the PNG Government to pay $NZ 23.7 billion in reparations; for damage done by mining, a reiteration of the claim made in April 1988. He also wanted 50% of mining royalties to go directly toward local development. Unless these claims were met, the mine would be put out of action permanently. The Chairman of BCL, CRA Executive Don Carruthers, warned PM Namaliu that if the situation deteriorated further, CRA would withdraw from BCL. The PNG Government would then lose K10 billion per annum of CRA spending. CRA also planned spending K200 million on stripping Hidden Valley in the Morobe Province in 1989. That plan has been put on hold. Namaliu accused Carruthers of panicking, although he himself must have been worrying about the reaction of private foreign BCL investors to the events in Bougainville.

The situation on Bougainville took a worse turn following events on March 17 1989. In an incident unrelated to the mining stand-off, a gunman with a semi-automatic rifle killed two plantation workers and injured five others at Arova Plantation, a vendetta for the murder of a woman the week before. The event triggered riots in the towns of Toniva, Kieta and Arawa. The Arova International Airport runway was cratered by explosives, two aircraft were destroyed and the terminal was burnt down. The PNG Government sent in 100 more police and troops from the PNG Defence Force, ostensibly to quell civilian unrest. Their presence led to further conflict with Ona's men. On April 6, a patrol of 20 soldiers was ambushed near Irang Village by approximately 30 men armed with automatic weapons. Two soldiers were killed and one was wounded. The ambushers lost two men and had two wounded. What looked like a case of provincial unrest was now verging on rebellion and more than one PNG official must have wondered where Ona's men had obtained automatic weapons from. Their fears were not calmed by Ona's calls for Bougainvillean independence, which distanced him from his provincial government supporters.

Father Momis's attempts at mediation between Ona and the PNG Government had failed and a hostile backlash from PNG mainlanders was also growing. Bougainvillean students at the University of PNG and the University of Technology at Lae received death threats as Ona continued his campaign against BCL, blowing up yet another power pylon on April 15. The Panguna mine was shut down for two days, and sporadic shoot-outs between PNG forces and saboteurs continued.

By May, various media sources placed the death toll somewhere between 11 and 17, including seven police, three soldiers, and John Ampana, Ona's second-in-command, who was killed in an ambush. Those wounded, numbered in the dozens, including police, soldiers, civilians, saboteurs and, on May 23, eight mine workers injured when four BCL buses were hit with automatic fire from One's men. This was in spite of the Panguna mine having been officially closed down on May 15. BCL has stated that work won't recommence until the violence stops. Government forces have also shown an increasing willingness to use violent means. Catholic priests on Bougainville have reported locals being tortured by Defence Force troops, who now number over 700 on the island.

From May 31 a truce was declared on Bougainville and the PNG Government has offered another round of negotiations, including the offer of 19% ownership of the mine to landowners. PM Namaliu described this as "the price we have to pay to preserve our national unity". Whether or not there will be another slide into violent conflict will depend on the PNG Government negotiating a settlement that satisfies the demands and interests of a number of groups - local landowners (both elders and young militants like Ona), local government, the 4,000 Australians and other employees working on Bougainville for BCL, foreign investors, and the PNG mainlanders. All this has to be done without disrupting PNG's economy even more and destroying national unity. As none of these aspects exist in isolation but are all interdependent, the PNG Government is in a very tricky position.

Originally published in CANTA No.14, 19 June 1989 p. 10.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

4. Vanuatu 1990: Ten Years Beyond Pandemonium

Formerly the New Hebrides, Vanuatu became an independent state in July 1980. Wayne McCallum looks at Vanuatu's path to independence, and some of the issues the country has faced in its first decade.

Although Vanuatu is a young nation with a relatively small population, situated in an isolated part of the globe, the country had a high profile in Pacific politics in the 1980s. Vanuatu is an archipelago of about 80 islands lying around 960km west of Fiji and 400km north-east of New Caledonia. The predominantly Melanesian population, estimated at 140,200 in 1987, speaks 111 languages; a linguistic variety unrivalled in concentration anywhere else in the world. Of those languages, just three have official status - English, French, and Bislama, the local lingua franca.

That a nation could be created out of a scattered chain of islands, with such a variety of languages, is all the more surprising given the divisive form that European colonial rule took in the archipelago for nearly a century prior to 1980. In 1887, Britain and France set up a joint commission for the New Hebrides, as Europeans had named the archipelago. By 1906, the colonial entente was furthered when the two powers formed the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides. The Condominium was essentially a compromise solution in an era of great power colonial rivalry. Neither Britain nor France was prepared to claim the New Hebrides unilaterally, but neither wished to relinquish the territory to the other party, or to Imperial Germany, which at that stage had territory in the South Pacific.

The result of the Condominium was a divisive administrative and cultural influence over the territory’s inhabitants. Britain and France each had a Resident Commissioner in the New Hebrides. There were two administrative budgets, and two foreign currencies in use. There were two police forces. And, perhaps more importantly, there were two education systems, both the product of missionary activity. The French-language schools were administered by Catholics, the English-language ones by Protestants. Those Melanesians who were introduced to European culture did so through rival education systems with outlooks tinged by European nationalism and sectarianism. Little wonder that the local Anglophone nickname for the Condominium was “Pandemonium”.

And the Condominium brought European settlers. By the end of World War II, over 36% of New Hebridean land was owned by foreigners. This European penetration on tribal land gave the original impetus to local Melanesian political parties. In 1971, the first New Hebridean political party, Nagriamel, based on the island of Espiritu Santo, petitioned the United Nations to prevent further land sales to US business interests. That same year, an Anglican priest, Walter Lini, cofounded the New Hebridean Cultural Association. In 1972, it changed its name to the New Hebridean National Party, and by 1977 had made its focus more specific with another name change to the Vanuaaku Pati (Our Land Party).

At the same time as the beginnings of local Melanesian nationalism, the Condominium was also going through changes. Whereas previously, both Britain and France had been careful to maintain a passably even level of influence over the New Hebrides, by the early 1970s it became apparent that Britain's interest in the Condominium was flagging. In line with its policy of reducing its colonial influence in the Pacific and elsewhere, Britain wanted to reduce its level of funding to the New Hebrides and eventually withdraw.

France, on the other hand, was clearly interested in staying. The French Government feared that if the Condominium collapsed and the New Hebrides became independent, a wave of Pacific nationalist sentiment would spread to its other Pacific territories. The French borrowed the theory of the “domino” effect much beloved by the US in its analysis of South East Asian politics in the fifties and sixties, and translated it to a Pacific setting.

French analysts predicted that if the New Hebrides became independent, it would serve as a base for the independence movement in New Caledonia (a Territory in the midst of a nickel export boom in the early 1970s), and would fuel independence claims in French Polynesia (the base for France's nuclear testing programme). Ten years after independence, such fears have yet to be realised.

With the British wishing to reduce their presence in the New Hebrides in the 1970s, France saw a good opportunity to further its own influence over the territory by increasing aid. France hoped that by raising the level of educational and local development funding, on Santo in particular, that it would gain the gratitude and support of a Melanesian Francophone majority in the islands, which would oppose independence and be sympathetic to a continued French presence, with or without Britain. The basis for this movement came with the founding by French colons (colonists) of the Union des Communautés des Nouvelles Hébrides (UNCH), an anti-independence coalition party. Nagriamel was a major component of this coalition, which was also called the Modérés, or Moderates.

Despite all this, or perhaps because of it, the power of the Vanuaaku Pati continued to grow in the late 1970s. The VP felt confident enough of its electoral power to boycott the November 1977 election in order to protest the Condominium's unwillingness to grant a referendum on immediate independence. Talks were held between Britain, France, and local government representatives in 1977, and a tentative date for independence some time in 1980 was set. The VP felt the Condominium was merely stalling and wanted faster action.

The Modérés were elected unopposed in November 1977, with an overwhelming majority, but their performance in government was so poor that the Chief Minister, George Kalsakau, decided to include VP representatives in ad hoc committees. By December 1978, the Modérés had agreed on a coalition with the VP in the Government of National Unity. The Government began working towards independence, to take place in 1980. In September 1979, a constitution was adopted and independence was scheduled for July 1980.

It became clear in 1979 that the VP would be the dominant force in local politics following independence. The VP won 26 out of 39 seats in the Representative Assembly during the November 1979 election. Overall, the VP gained 62.5% of the vote, with majorities on every island, including Modéré strongholds like the islands of Santo and Tanna. The new Prime Minister, Walter Lini, had a powerful support base as a result. Such a level of success came as a surprise to the French and British, and spurred on secessionist plans on Santo and Tanna. Jimmy Stevens, the leader of Nagriamel, had been announcing plans for Santo's secession since 1976. His plans had been encouraged by the right-wing US Phoenix Foundation. The Foundation hoped to use an independent Santo as a tax haven where it could, set up a laisser faire capitalist paradise. The Foundation supplied Stevens with a radio station, wrote up a constitution and even arranged the printing of passports and the manufacture of national flags. Early in 1980, the Condominium moved to stop the Phoenix Foundation's plans. The Head of the Foundation, Michael Oliver, along with 13 of his associates, were declared prohibited immigrants. Neither Britain nor France desired a backdoor American presence on Santo complicating independence.

In June 1980, Jimmy Stevens declared the Independent State of Vemarana, consisting of the islands of Santo and Tanna. Walter Lini claimed in his book Beyond Pandemonium that Stevens was aided by both French colons and the French Government in his secessionist plans. Specifically, a French gendarme was believed to be training the Nagriamel militia and a French warship was believed to be delivering arms and supplies to Santo. While the French Resident Commissioner, Inspector General Robert, had proclaimed the French Government's support for the VP's legitimacy and independence goals, the VP believed that France had a secret agenda actively opposing independence.

If so, France's aims were weakened by Jimmy Stevens' declaration of secession prior to Vanuatu's independence. French colons on Santo had hoped for secession after Vanuatu's independence day, on 30 July 1980. Thus they hoped to weaken the VP’s legitimacy and the authority of newly-independent Vanuatu. Stevens' secession declaration prior to Vanuatu's independence meant that Nagriamel had weakened the legitimacy of the Condominium over the New Hebrides instead.

Despite repeated requests from Lini's Government throughout June 1980, the Condominium made no attempt to control events on Santo. Lini and his Government wanted a state of emergency to be declared. On 26 June 1980, Lini wrote a letter to the French and British Resident Commissioners, demanding to know if they would uphold law and order in the New Hebrides, as pledged under their 1914 Protocol. He received no reply. The French were clearly unwilling to take any action against Nagriamel. They refused to send gendarmes to Santo, and when the British airlifted 200 Marines to port Vila, France accused Britain of over-reacting and refused to support their unilateral deployment on Santo.

No Condominium action was taken until 20 July, ten days before independence, when a joint force was airlifted to Santo. 100 British Marines and 100 French paratroops occupied Luganville, the largest centre on Santo, in a mutual display of law and order. The troops stayed in Luganville with a French destroyer moored off-shore, while Nagriamel retained unhindered control of the rest of Santo.

The 30 July 1980 Independence Day came and went peacefully on Santo. On 17 August, Walter Lini ordered the French and British to withdraw their troops. In their place, Papua New Guinea's 90 man strong “Kumul Force” was deployed on Santo, along with the newly-established Vanuatu Mobile Unit. Within three days, the force had re-established a level of control that the Condominium troops had failed to achieve in four weeks. Forty people, including seven French colons, were arrested. There were minor skirmishes with Nagriamel supporters and a French trained maquis, but Vemarana's independence was at an end.

In the subsequent trials, Jimmy Stevens was sentenced to 14½ years of imprisonment. Timothy Welles, his second in command, received an eight-year sentence. Most of the others found guilty of involvement in the secession received four to eighteen months. Those with longer sentences were freed in February 1982, when the VP decided that past differences should be buried.

Differences with France were not so easily buried. Vanuatu retained diplomatic relations with France after independence, but they have periodically been strained. In February 1981, the VP expelled the French Ambassador to Vanuatu following the deportation from New Caledonia of the VP Secretary-General, Barak Sope. Sope was visiting New Caledonia to attend a meeting of the Front Indépendantiste. France suspended aid to Vanuatu, but by March 1983 an $AUST 6.9 million aid agreement had been signed and a new French Ambassador was appointed to Vanuatu. Vanuatu's sympathy for the Kanak independence movement in New Caledonia has been treated warily by France, and there has been much hostile press generated against Vanuatu in New Caledonia, where French loyalists still pay heed to the “domino” theory.

In June 1982, relations between France and Vanuatu were once again put under pressure when Vanuatu formally claimed the deserted Matthew and Hunter Islands, located around 200km south of the island of Aneityum. The islands effectively increased Vanuatu's maritime zone. The claim was disputed by France. Although for decades French and British maps had listed the two islands as being part of the New Hebrides, France had formally claimed the two islands as part of the Territory of New Caledonia in 1975, conveniently forgetting their status as part of the Condominium. Nonetheless, Vanuatu Government representatives landed unchallenged on the islands in March 1983, and raised Vanuatu's flag there.

Vanuatu has had an active foreign policy. It is the only Non-Aligned Movement Member in the South Pacific, and has vigorously opposed the presence of nuclear arms and testing in the South Pacific, an opposition which predates New Zealand's adoption of an anti-nuclear policy following the Labour Government's election in 1984. On 5 February 1982, Vanuatu refused entry to the US warships USS Marvin Shields and the USS Robert E. Peary as the US Government would neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear-arms on board the ships. In 1983, Walter Lini declared Vanuatu's nuclear free policy, a year before New Zealand's adoption of one.

Vanuatu has differed with the Australian and New Zealand Governments over nuclear free policy, claiming that policies set in Wellington and Canberra don't go far enough in opposing nuclear weaponry. In 1985, Walter Lini refused to sign the Rarotonga Treaty, which advocated a “nuclear-free” Pacific. He pointed out that the Treaty still permitted planes and ships carrying nuclear weapons to visit South Pacific countries, and move around the South Pacific unopposed.

Vanuatu's nuclear-free stance has not been welcomed by the US. Nor has Vanuatu's position as a non-aligned nation in the South Pacific been perceived positively by the US.

Other parts of Vanuatu's foreign policy have been regarded with some alarm by the US. Vanuatu's diplomatic recognition of Cuba in 1983, for example, drew over-reactions not only from the US Government, but from Australia and New Zealand. There was talk of Vanuatu being turned into the “Cuba of the South Pacific” by communist interests. That not only the US, but New Zealand and Australia had diplomatic relations with numerous Eastern bloc states at the time was not regarded by those three nations with the same alarm. Why a double standard should have been adopted for Vanuatu is uncertain. Considerably less attention was drawn to Vanuatu's creation of links with the EEC, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Asian Development Bank, and the British Commonwealth around the same time. Given Vanuatu's determination to retain an independent foreign policy, and its profitable status as a tax haven to Western multi-nationals, it's unlikely Vanuatu would ever become the Cuba of the South Pacific.

Nonetheless, hysteria over Vanuatu's foreign links has persisted. A good example is when the US Ambassador to the United Nations, General Vernon Walters, visited Vanuatu in April 1987. During his stay he “discovered” to his horror that two Libyans were staying at Port Vila's Intercontinental Island Inn at the same time as he was. Walters fuelled speculation that the pair were officials from the Foreign Liaison Bureau who had arrived to set up a Libyan diplomatic post in Vanuatu. If this was the case, then according to the journalist David Robie, the pair failed miserably in their assignment. They only spent 19 days in Port Vila, barely leaving their hotel room the whole time they were there. The Vanuatu Government finally expelled them for breaching protocol and not presenting their credentials to Government representatives.

Much was also made of the presence of a VP representative at a March 1986 conference in Libya for representatives of independence movements. Pacific Islands Monthly (June 1986) interviewed the VP Secretary-General, Barak Sope, as part of an exposé of supposed Libyan influence in the South Pacific. Sope denied that Libya was funding the VP, and downplayed the prominence that PIM had given to the VP representative's attendance of the Libyan conference.

Despite US fears of Vanuatu setting up diplomatic relations with the USSR, there has been little interaction between the two nations. When Vanuatu negotiated a fishing deal with the USSR in January 1987, Australia, New Zealand and the US regarded the negotiations with suspicion. Their representatives issued warnings of the dangers of encouraging a Soviet presence in the South Pacific. The fishing deal lapsed, presumably for want of Soviet interest. Similar fishing arrangements negotiated by the Soviet Union with Australia and New Zealand have proven more productive, the irony of which has not been publicly noted by representatives of the Australian and New Zealand Governments.

Internally, Vanuatu has had more pressing problems than the Cuban, Libyan and Soviet phantoms conjured up by Australian, New Zealand and US foreign affairs experts. Although Walter Lini has retained his post as Prime Minister at the head of a Vanuaaku Party Government through different elections over the last decade, there have been recurring challenges to his leadership.

In March 1983, Walter Lini lost three members of his six member Cabinet in a bout of political infighting. Lini sacked the Deputy Prime Minister and the Minister of Home Affairs after they questioned his leadership. The Ministers of Education and Transport resigned in sympathy. In March and April 1983, there were two unsuccessful No Confidence motions put to the Representative Assembly as a result of Lini's conduct as Prime Minister. The President, Ati George Sokomanu, publicly aligned himself with Lini's critics. In April 1983, Lini announced that Vanuatu had balanced its finances, but opposition critics questioned whether obtaining a $US350 million loan to do so was wise. They claimed that the interest payments alone could cripple Vanuatu's economy. Nonetheless, Lini held his leadership in the December 1983 elections.

Disputes peaked again following the November 1987 election. Lini suffered a stroke in February 1987 and Barak Sope had unsuccessfully tried to take his place as Prime Minister, before the election. Lini included Sope in his Cabinet as Tourism and Transport Minister following the election, but there was speculation over how far Lini's goodwill extended when the Government froze the assets of the Vila and Luganville Urban Land Corporations. Sope had been a Board Director since 1981 and this was seen as a move by Lini to limit Sope’s power. Allegations were made at the time that Sope had misappropriated 750 million Vatu ($NZ 1 million) of company funds.

Sope lead a 3,000 strong rally against the Government's seizure of the Corporation. The rally marched on the Prime Minister's Office in Port Vila on 16 May 1988. After the rally, around 150 militants who had participated got drunk and rampaged through the Kumul Highway shopping area. One man was killed and others were injured in violent rioting. Lini sacked Sope as a Minister after the riot.

In July 1988, Sope, along with four VP MPs and 18 opposition MPs, were expelled from the Representative Assembly for their criticisms of Lini's response to the riot. Sope formed his own party, the Melanesian Progressive Pati, in September 1988, and in October the VP expelled 128 VP members for their support of the MPP. Sope persuaded President Sokomanu to dissolve Parliament and set new elections for February 1989. Lini challenged this through the Supreme Court, which declared Sokomanu's attempted dissolution of the Government illegal and unconstitutional. In February 1989, President Sokomanu, Sope, and two other MPs were jailed for their involvement in the attempted dissolution. In April 1989, a Court of Appeal released all four, saying there was a lack of evidence to support claims made against them.

These political events have tended to attract attention away from the economic problems facing Vanuatu in recent years. After growth rates between 3-5% from 1983 to 1984, Vanuatu's economy declined following 1985. Two cyclones in January 1985 devastated the country's primary export, copra, that year. This, combined with a drop in world prices for copra, along with beef and cocoa, other major exports, led to an almost 50% drop in Vanuatu’s 1986 export total compared with the 1985 total. Nonetheless, gross domestic product increased 2% in 1985.

Vanuatu is still dependent on foreign aid for its economic well-being, particularly to repair the destruction caused in the islands by cyclones. However, since independence, the Government has made attempts to expand economically. Port Vila's financial centre has been expanded and there is another move to encourage tourism in Vanuatu. Tourism which, potentially, is Vanuatu's major industry, declined in the mid-1980s.

Even with its firm sense of independence, Vanuatu faces many economic and political challenges in years to come. Its volatile party politics will need restraining if the Government is to retain internal and international credibility. Economically, Vanuatu will, like New Zealand, need to broaden its range of exports to withstand global market fluctuations, but has considerably less development funding than New Zealand with which to do this.

Originally published in CANTA No. 14, 9 July 1990 pp. 10-11.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1990.

5. Johnston Atoll 1990

The U.S. Army caused quite a commotion in 1990 with its plans to destroy chemical weapons on Johnston Island. Wayne McCallum looks at this and other past U.S. military activities on the Atoll, and the convoluted issue of what to do with all the chemical weapons.

Johnston Atoll is an unincorporated United States territory lying 1,300km southwest of Hawaii. The U.S. military has long favoured the Atoll for activities deemed too risky or secret to undertake elsewhere. The Atoll is comparatively remote. After Hawaii, its closest neighbours are the Line Islands and the Marshall Islands, over 1,500km distant to the south-east and south-west respectively. For all this, Johnston Island, with its military airstrip, is conveniently located only two hours' flying time from major U.S. military bases in Hawaii.

Formerly a bird sanctuary, Johnston Atoll's feathered inhabitants had their sanctuary disturbed when the United States Air Force (USAF) tested two thermonuclear bombs there in 1958. Nuclear testing continued on the Island in 1962, when ten live Thor nuclear missile launching tests were conducted. The aim was to test the detonation of the missiles' nuclear warheads in space. Only eight of these missiles left the earth's atmosphere: one went off course and crashed in the ocean (its nuclear warhead was never recovered), and the other exploded on the launch pad, showering the Atoll with radioactive plutonium, which took weeks to "clean up".

In 1962, the U.S. signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty, which forbade any further atmospheric nuclear testing. Nonetheless, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff decided to keep their options open by maintaining a "National Nuclear Test Readiness Centre" on Johnston Island. The Centre, run at a cost of $US12 million annually, has been kept on standby ever since, according to Owen Wilkes, the New Zealand peace researcher. Should the U.S. decide to abandon its Treaty obligations, the Centre will be used for atmospheric nuclear testing preparations.

In the 1960s, two anti-satellite missile launchers were also installed on Johnston Island. The system was a small-scale predecessor of the "Star Wars" space defence system later mooted by the Reagan administration in the 1980s. The launchers were dismantled in 1975 after being badly damaged in a hurricane. It was just as well, because the U.S. Government had previously signed a treaty banning the use of nuclear weapons in space and Owen Wilkes claims the two launchers were the source of some embarrassment to the U.S.

The same 1975 hurricane damaged other facilities on Johnston Island. Roofs were blown off storage buildings holding canisters with 13,000 tonnes of mustard gas. The gas had been shipped to Johnston Island from Okinawa in 1971, when U.S. Government formally handed back sovereignty of the island to Japan. The Japanese, understandably, had no desire for the stockpile to remain on Okinawa. The gas, including mustard gas varieties H, HD and H7, was still being held on the Island in 1990.

Another stockpile of goodies on Johnston Island at the time of the 1975 hurricane were 18 million litres of dioxin-carrying Agent Orange defoliant. The defoliant was surplus stock from the Vietnam War and was shipped to Johnston Island in 1970. Like the Okinawa cache of gas, the Agent Orange had survived an earlier hurricane on Johnston in 1972. The Agent Orange wasn’t disposed of until 1976. The 18 million litres were loaded aboard the Dutch-owned incinerator ship Vulkanus which was parked 200 km downwind from the Atoll. It took over six weeks for the entire stack to be burnt off, with the waste being released into the atmosphere.

Despite all this military activity in the past, Johnston Island has not attained the same public notoriety that other Pacific nuclear test facilities such as say, Moruroa Atoll, have had. At least, that is, not until 1990, during which debate over U.S. military activity on Johnston Island centred on plans by the U.S. Government to use the base for disposing of chemical weapons from the 1971 Okinawa stockpile, reported by the U.S. Army to be in a state of deterioration in the humid, salty marine environment on Johnston Island. The U.S. Army’s proposed solution was the Johnston Atoll Chemical Disposal System (JACADS). JACADS consists of main furnaces, air purification equipment, and robotic machinery with which chemical munitions can be assembled. In 1983, the U.S. Army prepared its first Environment Impact Statement (EIS) on the effects JACADS would have on the Atoll. A supplementary EIS was released in 1988, and another in February 1990. The somewhat predictable conclusion of the EIS was that the destruction of chemical weapons on Johnston Island could be undertaken in a "safe and environmentally acceptable manner".

JACADS was originally constructed to dispose of the 13,000 tonnes of the Okinawa gas stockpile. It is the first major U.S. facility of its kind and, if successful, the U.S. Congress intends to grant permission for the construction of eight similar units in the mainland USA. These eight units are to be built in Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Oregon and Utah, and are intended to deal with 30,000 tonnes of chemical weapons stored in the mainland U.S. by 1997, leaving all but 5,500 tonnes of its chemical weapon stocks under a bilateral agreement with the USSR The bulk of the total U.S. chemical weapons stockpile is stored on the mainland U.S.

As a pilot project, JACADS experienced some problems. In October 1989, John Murtha, the Chairman of the U.S. Congressional House Defense Appropriations Committee, spoke of “managerial problems” and of difficulty with the “overall reliability” of JACADS machinery. These problems are supposed to have been dealt with, but Owen Wilkes claims that JACADS is now three years behind schedule as a result.

The first test incineration of the Okinawa stockpile took place late in June 1990. On 26 June, Greenpeace's Rainbow Warrior circled Johnston Atoll in protest. The U.S. Army has set 1994 as the year by which the incineration of the original gas stocks on Johnston Island was to be completed.

Greenpeace has opposed JACADS since 1983. It believes that incineration of the gases “will release highly poisonous wastes directly upwind of the Marshall Islands, and this poison will accumulate in migratory fish such as tuna, swimming near the island". (Greenpeace, Spring 1990). The prevailing nor-easterly trade winds and the westward ocean current around Johnston Atoll mean that any waste from military activities on Johnston travels directly away from the mainland and towards the Marshall Islands to the east. Greenpeace believes that JACADS will also release toxic waste into the ocean and atmosphere. Owen Wilkes stated in Peacelink (July 1990) that JACADS incinerator smokestacks would be “scrubbed” by spraying seawater down them, with the contaminated water being drained away into the ocean.

As an indirect response to Greenpeace's unfavourable comments on JACADS, the U.S. Army decided not to dump solid waste from the JACADS incinerations into the sea. Replying directly to Greenpeace's belief that JACADS would release toxic compounds such as polychlorinated dibenzo dioxins (PCDDs) and furans (PGDFs) into the marine environment, the U.S. Army claimed that “a 99.99% destruction and removal efficiency is reached for each hazardous compound destroyed”. They also pointed out that only the incineration of mustard gas, not nerve gas, produces PCDDs and PCDFs.

Greenpeace remains categorically opposed to JACADS. It opposes the use of any form of chemical weapons incineration on the grounds that the process produces waste. Greenpeace’s Pacific campaign co-ordinator in Washington, Sebia Hawkins, stated: “Of course, Greenpeace applauds efforts to rid the world of chemical weapons but incineration is not the answer, and more appropriate methods must be found”.

Greenpeace's stance begs the question “what other methods?” Trevor Findlay of the Australian National University Peace Research Centre pointed out in a controversial article published in the Centre's May 1990 issue of Pacific Research, that the JACADS facility is the best there is, and no current disposal alternatives to high temperature incineration of these gases exists. It took several years to develop JACADS, and it would take just as long or longer to develop another disposal system which may or may not prove more efficient. In the meantime, those 20-year-old canisters would still be corroding on Johnston Island.

Another Greenpeace demand is that a destruction process be found which does not produce any residues. Even Owen Wilkes, by no means favourably disposed to JACADS, commented: “… their (Greenpeace's) demand that "no material whatsoever" be left after disposal is obviously impossible to satisfy, for [a] reason obvious to anyone with even dim memories of high school chemistry lessons - something to do with a law about the conservation of matter”.

The U.S. has committed itself under Public Law to destroy most of its chemical weapons by 30 April 1997. It is highly unlikely this deadline would be met if JACADS was discarded and research into new destruction methods for the gas was undertaken. Owen Wilkes also pointed out that U.S. Public Law is the main reason why the Okinawa stockpile is on Johnston Island to begin with - it was considered too dangerous to store in the mainland U.S., but not too dangerous to store upwind of the Marshall Islands apparently.

A further complication to the issue came with the U.S. Army's 8 March 1990 declaration that they would be removing all U.S. chemical weapons stockpiled in West Germany by the end of 1990. The U.S. had originally planned to move their gas stocked in West Germany in 1992, but the West German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, moved the date forward to the end of 1990, to improve his chances of winning the December 1990 General Election. The U.S. was therefore forced to act sooner than it had planned, not a good situation when you are shifting something as potentially lethal as large quantities of nerve gas.

The U.S. gas stockpile in West Germany, totalling 435 tonnes of G B (Sarin) and VX nerve gas, contained in approximately 100,000 eight inch and 155mm projectiles, comprises less than 1 % of the U.S. global chemical weapons stockpile.

The U.S. Army announced that it planned to ship the gas to Johnston Atoll between July and September 1990. The West German stockpile's incineration was planned to take place after the destruction of the Okinawa stockpile, which was to be completed some time in 1994. The total cost for the destruction of the two stockpiles on Johnston was projected to be $US3.1 billion.

After the announcement, Greenpeace stepped up its protests, stating that the gas from West Germany shouldn't be shifted to Johnston Island due to the potential danger it represents for Marshall Islanders. Owen Wilkes asked "If it is as safe (to dispose of) as the U.S. Army says it is, then they should do it in Germany - in the Ruhr Valley perhaps, where a little bit of extra pollution will hardly be noticed". It was a facetious comment, in that West Germany is not responsible for the gas and has no desire to run the risk of having it disposed of on its territory. Also, no U.S. Army facilities exist in West Germany for the destruction of the gas, and it is unlikely that the West German Government would be prepared to approve the construction of such facilities, even if they wanted to retain the gas on their territory for however many years this would take. The question of what response West German environmentalists should take to the issue has caused some division between them. West German environmentalists are generally unfavourable to the continued presence of the U.S. gas in West Germany, but the solution of shifting it to the Pacific, where it could prove dangerous to the health of Pacific Islanders, isn't seen by many as the best solution.

The move began in late July 1990. An 80-truck convoy was needed to transport the 20-year-old stockpile. West German environmentalists protested the path that the convoy took through urban areas to the port facilities for loading.

On 3 August, The Press reported that Greenpeace and U.S. environmentalists had filed a lawsuit in an attempt to block the shipment of the stockpile to Johnston Atoll. They felt that shipping the containers halfway around the world was a dangerous action.

But the other option poses problems too. The weapons could be shipped for stockpiling to the U.S., but this would clearly be unacceptable to the U.S. environmental lobby. Even the U.S. Army has stated its unwillingness to ship the chemical weapons to US port facilities so that they could be transported for storage somewhere in the mainland USA. The U.S. Army feels that transporting the chemical weapons through American urban areas entails an unacceptably “high risk”, although they have not publicly expressed qualms about doing the same thing in West Germany. It's odd that they should make this belated statement though, having regularly transported chemical, bacteriological and nuclear weapons along the highways and railways of the mainland United States over the last forty years.

Also there's the problem that no disposal systems are currently operational in the mainland U.S. If the stockpile from West Germany was taken to the mainland U.S., there would be little to do with it except add it to the existing stockpile there. Given the age of the chemical munitions, the U.S. Army regards this as an undesirable and risky option.

Instead, it is more convenient to the U.S. Army to shift this, less than 1% of its total chemical weapons stockpile, to distant Johnston Island for destruction, where it is unlikely to endanger the lives of any American citizens other than the military personnel on Johnston. Out of sight, but not out of mind. If JACADS is successful, then the U.S. Army can conduct further chemical weapons incineration closer to home whilst assuring American citizens that it poses no danger to them.

The South Pacific Forum at Vila declared its support for the burning of the Okinawa stockpile on Johnston Island, but opposed the transport of further gas from West Germany. In doing so, the Forum hoped to express its disapproval of nations using the Pacific as a dumping ground for dangerous waste, but the presence of the Okinawa cache on Johnston has, to some extent, pre-empted this disapproval. The U.S. is unlikely to change its plans at such a late date. The New Zealand Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer declared his opposition to U.S. plans, but was reported by The Press (2 August 1990) as saying he was “pessimistic” about the chances of the U.S. stopping its plans.

Marshall Islanders are now no doubt hoping that JACADS is as safe as the U.S. Any claims it is. It's not very reassuring that the U.S. military has a long track record of underestimating the health dangers resulting from its past atmospheric nuclear testing, both in the Pacific and Nevada. Also worrying, as Owen Wilkes points out, is the prospect of the chemical weapons being stacked until 1994 on a narrow strip of land between the ocean and the 3km runway on Johnston Island. USAF planes use the Island's runway daily, and it will only take one off-course aircraft crashing into the gas containers to cause quite a disaster. And if you're wondering about the USAF's flight safety record, the number of their planes involved annually in air accidents of one sort or another, regularly runs well into double figures...

Sources

David Robie: Blood On Their Banner. Pluto Press 1989.

“Paradise In Peril”, Pacific Islands Monthly July 1990.

Trevor Findlay: “Green vs Peace? The Johnston Atoll Controversy”, in Pacific Research Vol. 3, No. 2 May 1990.

Greenpeace New Zealand Spring 1990, No. 54.

Owen Wilkes: “Chemical Weapon Burnoff in Central Pacific”, in Peacelink, July 1990.

The Press.

Originally published in CANTA No. 19, 13 August 1990 pp. 10-11.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1990.

6. National Does a Somersault on Nuclear Policy

The National Party's declaration on 7March 1990 that they had abandoned support for the United States'“neither confirm nor deny” policy on nuclear ship visits to New Zealand was described by the former NZ Prime Minister, Geoffrey Palmer, as one of the greatest somersaults in New Zealand history. Wayne McCallum looks at the history of National Party defence policy and the causes for their about face.

The National Party's decision in March 1990 to no longer directly support the United States' global nuclear deterrent, and adhere to Labour Government policy opposing visits by nuclear-armed ships to New Zealand, was greeted with surprise by many people both in and outside the peace movement. Only days after National leader Jim Bolger had stated National's support for ANZUS by the proposed reintroduction of US nuclear ship visits to New Zealand and declared a willingness to adhere to the US “neither confirm nor deny” policy, (see The Press 23 February 1990), he was arguing a totally different position. At his 8 March 1990 press conference, Jim Bolger clearly stated the National Party's new-found support for Labour Government policy opposing nuclear ship visits, and officially abandoning hopes of returning to ANZUS relations that existed under the Muldoon administration. Bolger claimed that since the signing of ANZUS in 1951, “... the National Party and the National Governments over the years have argued a strong, non-nuclear position in the world” and that “We have always been against nuclear weapons in New Zealand” (press conference transcript 8 March 1990).

It was a clear piece of revisionism, and such statements were scoffed at by members of the Labour Government, who enjoyed their only major 1990 policy victory over the issue. After years of National criticising the progress of the 1984 New Zealand Nuclear-Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Bill, through until its enactment in 1987, it appeared that National had finally admitted its defeat in the face of a popular labour policy and was now conducting a belated vote-catching turnaround in time for the 1990 General Election. Geoffrey Palmer commented that “Now we [the Labour Government] have the spectacle of the National Party trying to ride on our coat-tails” (Christchurch Star 9 March 1990).

So, depending on who you believed, National was either a totally non-nuclear party strengthening its resolve on anti-nuclear matters, or was engaged in an unprincipled abandonment of its former policy in order to chase votes. To find out which version is more correct, it is necessary to turn the clock back. The origins of the issue of National's involvement with the US nuclear deterrent dates back to New Zealand's signature of the ANZUS Treaty in 1951.