Tahiti Tiki Tour

by W.S. McCallum

Tahitian

tikis: Strangers in a strange land

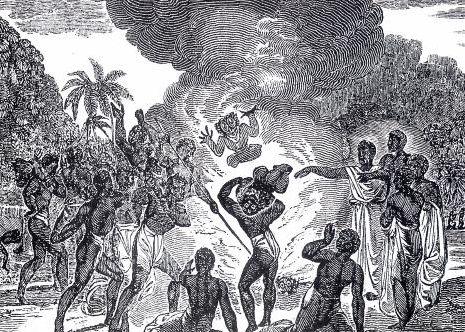

In 1815, as

part of his process of converting Tahitians to christianity, King Pomare II, at

the behest of missionaries from the London Missionary Society, ordered the destruction

of all of Tahiti's tikis:

Purged of

its craven idols, subsequently Tahiti effectively became tiki-free, with

Tahitian tikis becoming rare items by the end of the 19th century, to be seen

only in the collections of various European museums.

Nearly two

centuries later, and following a revival in Tahitian culture since the 1970s,

what is the state of tikidom in this strange Polynesian land where tikis were

effectively banned for so long?

These were

the thoughts I pondered as my flight from Auckland came in to land at Faa'a

Airport:

Tahiti’s

Tiki Carving Tradition

It is true

that the Tahitians were not well-known for tiki carvings, although they did

exist.

Traditional

Tahitian society was oriented more towards the arts of poetry, oratory, theatre

and dance than sculpture and figurative representations but, all things said

and done, being Polynesian, it did have tikis (or "ti'i" as they are

known in Tahitian). They were however not abundant and, also being sacred,

tended neither to be shown to visiting Europeans like Cook and Bougainville,

nor given to them as gifts.

Very few

survive, although they are held in the collections of various European museums.

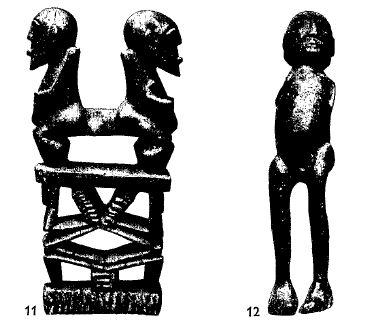

Here is an image of a female wooden figure held in the British Museum:

Canoe

ornament and carving, also from the British Museum:

Wooden fly

whisk handle (British Museum):

(Images

from Art ancien de Tahiti, by Anne Lavondès: Dossier 1, Société des Océanistes,

Paris 1968.)

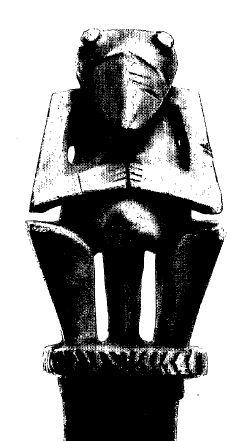

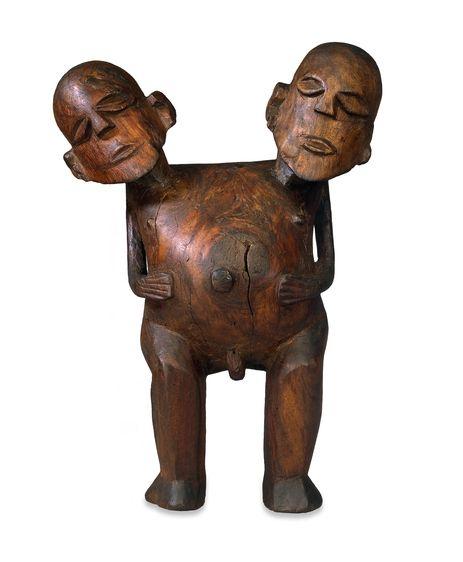

And here is

a two-headed figure also held in the British Museum collected by Lieutenant

Sampson Jervois of HMS Dauntless, which called into Matavai Bay, Tahiti in

1822:

(photo from

The British Museum website: http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/t/two-headed_figure.aspx

)

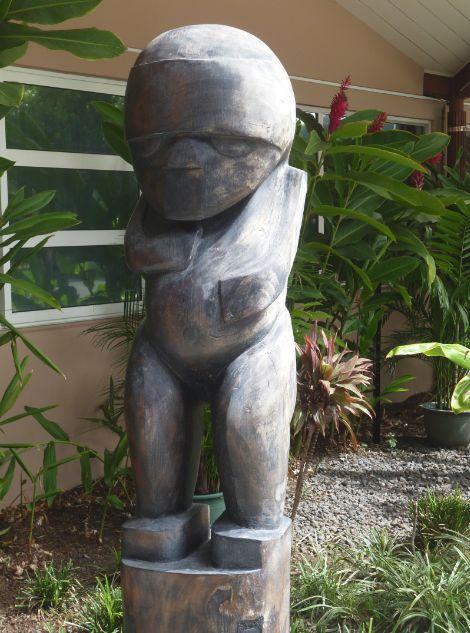

Although

they are few and far between, and were carved in recent times, there is the

occasional authentic Tahitian tiki on Tahiti. Here is one down on the

waterfront in Papeete, just behind the tourist information centre:

It is clear

what it was inspired by....

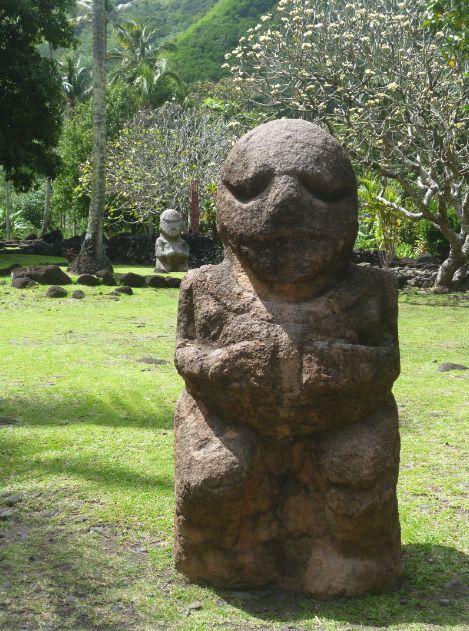

But as we

shall see, there are a fair number of tiki ring-ins and imposters populating

the landscape on Tahiti, no matter how old and authentic they may look in situ:

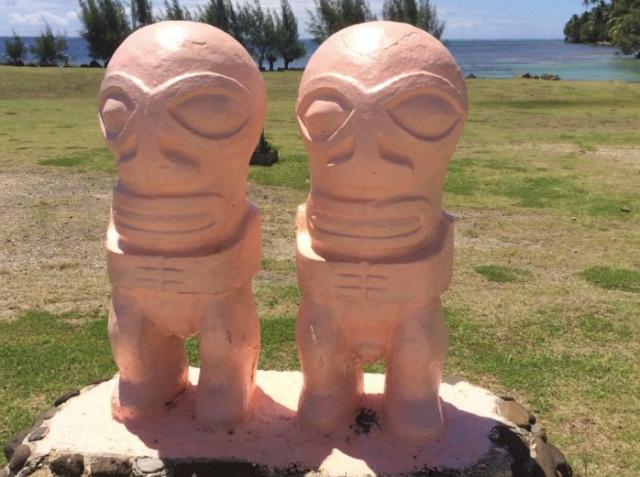

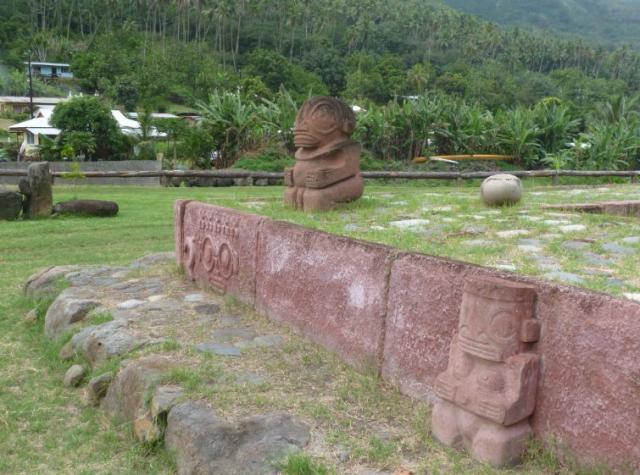

While these

fellows at Arahurahu marae on the west coast of Tahiti Nui may look right at

home, they are in fact strangers in a strange land. More to follow....

Tiki

Origins

The

majority of Tahiti's tikis, whether painted or carved, originate from the

Marquesas:

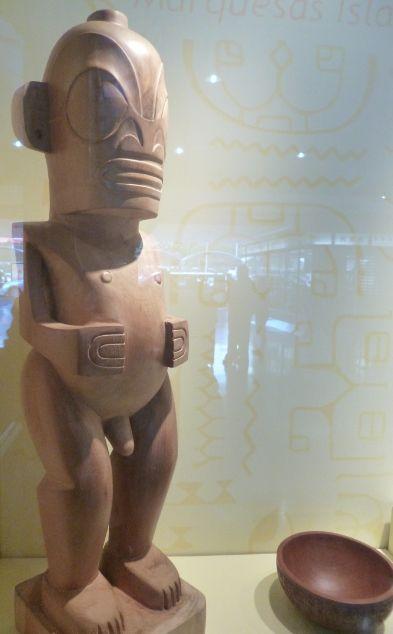

Mini-museum

display at Faa'a Airport: carving by Joseph Auch and Daniel Tamata, 2011. A

copy of a carving held in the Château-Musée de Boulogne-sur-Mer (France).

Twin

Marquesan tikis outside the French High Commissioner's building.

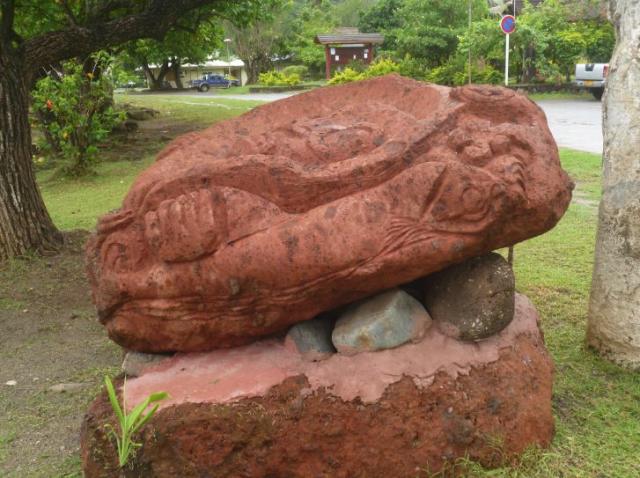

A

traditional Marquesan headhunter tiki outside the Fare in the grounds of

Papeete's City Hall (note the very Romano-Gallic-looking severed head ![]() )

)

A modern,

stylised Marquesan tiki at the intersection at the end of Rue Paul Gauguin.

Marquesan

tikis are not the only style to be seen in public statuary on Tahiti. Other authentic

styles do get a look-in:

Austral

Islands tiki on the grounds of the French Polynesian Territorial Assembly.

Also on

display at the Territorial Assembly are tikis from the Society Islands:

This one

looks Tahitian...

While this

female figure at the Territorial Assembly is a copy of a tiki collected during

Cook's second voyage, from somewhere in the Society Islands (1773).

Other tikis

on Tahiti are more generic:

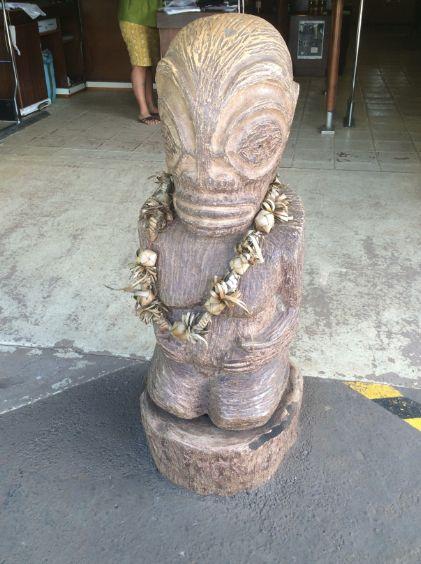

The first tiki

visitors to Tahiti see; Faa'a Airport arrivals terminal.

Staircase

tiki, Papeete market.

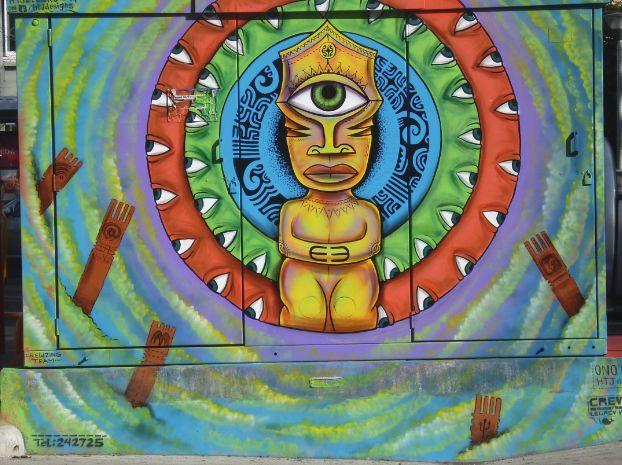

And some

are cheekily unconventional and defy categorisation:

Mural on a

power sub-station outside the McDonald's on Rue Général de Gaulle.

And getting

back to our very authentic-looking tikis at Arahurahu marae....

They are

actually castings of two female tiki statues from the island of Raivavae, in

the Austral Islands.

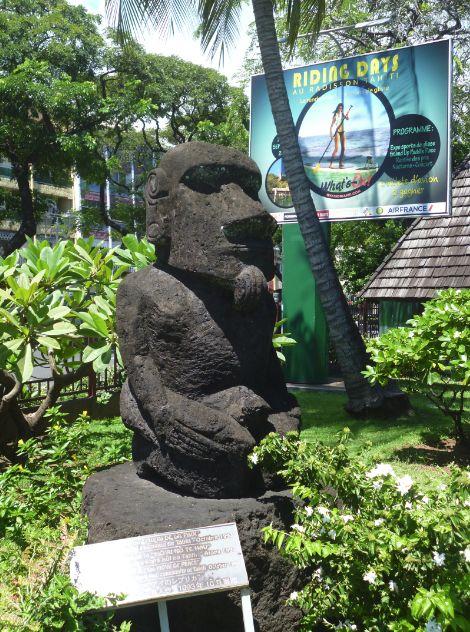

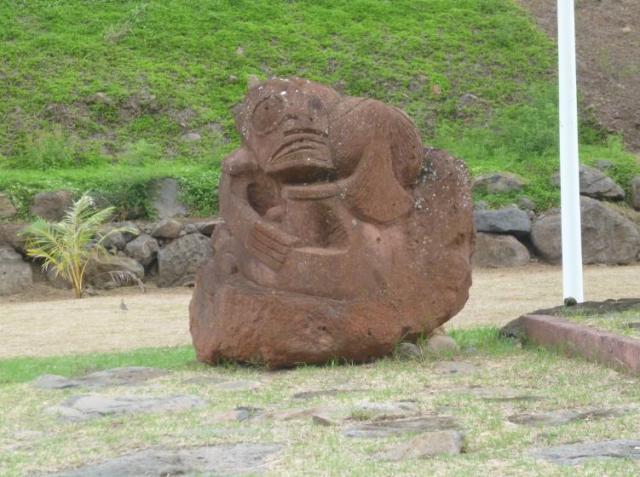

And then

there's this very well-endowed and goateed Easter Islander placed prominently

outside Papeete's tourist information centre who made me do a real double-take,

until I read the plaque in front of him, indicating he was a gift to the

Tahitians from the local Rapa-Nuian community.

To sum up,

Tahiti's tikis are now as varied as the population of the island itself, which

hosts islanders from all over French Polynesia and even further afield. In that

respect, they reflect the cultural diversity of 21st century Tahiti.

Very happily,

it is clear, on the eve of the 200th anniversary of King Pomare II's

destruction of the island's tikis at the behest of a coterie of English

missionaries, that Tahiti has been thoroughly recolonised by tikis, some of

whom have come from very far afield indeed.

And it

looks like they are there to stay. ![]()

Next

instalment: tiki signage and graphic art on Tahiti

Tiki

Signage and Graphic Art

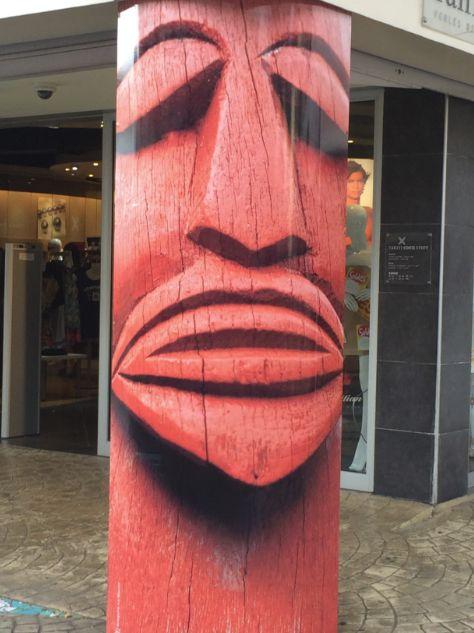

Tiki photo

plastered on a pillar outside a boutique, Promenade de Nice, Papeete

I was

interested to see the extent to which tikis had infiltrated greater Papeete's urban

landscape, above and beyond public statuary. Consequently I spent a lot of time

wandering around, taking photos, and getting a mix of reactions from the

locals, ranging from "who's that crazy Popa'aa photographing the

tikis?" through to an appreciative honk and the "hook'em horns"

sign from a passing driver who nodded approvingly at my tapa-style shirt (made

in NZ circa 1970).

On

occasion, the local signage goes so far as to feature an actual old-style tiki

carving:

Or the tiki

is integrated into the company's logo:

Sometimes

the tiki image is drawn from the past, as in the case of this now derelict hotel

on the Boulevard Pomare:

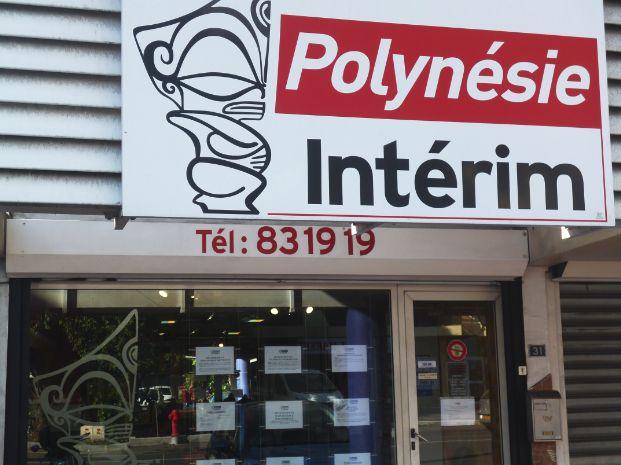

At this

temp agency on Avenue Georges Clemenceau, in addition to featuring in the

signage itself...

... the

tiki is even etched onto the office window:

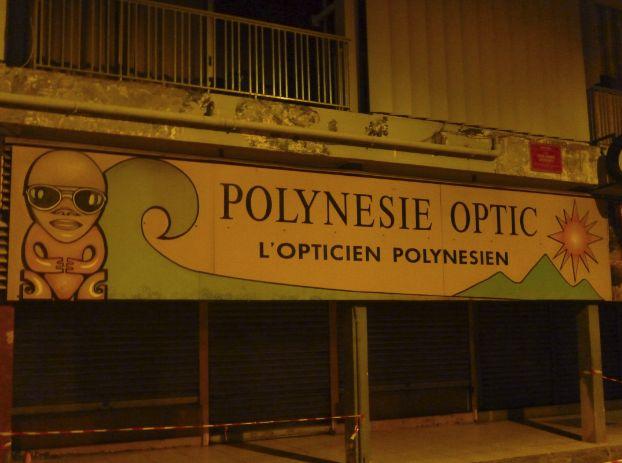

Tikis are

used to promote the sale of all manner of products - sign outside an

optician's:

While such

signs are hard to miss, some are so small and discreet you can easily walk past

them and not notice: a surfing tiki on a post outside a tee-shirt store:

And then

there is the resolutely modern 21st-century tiki graphic:

The tiki apartment

building is not only to be found in California; here is one in Pirae, on the

outskirts of Papeete:

Detailed

view:

The

apartment building looks like it was built in the 1960s, judging from its

general appearance.

And the

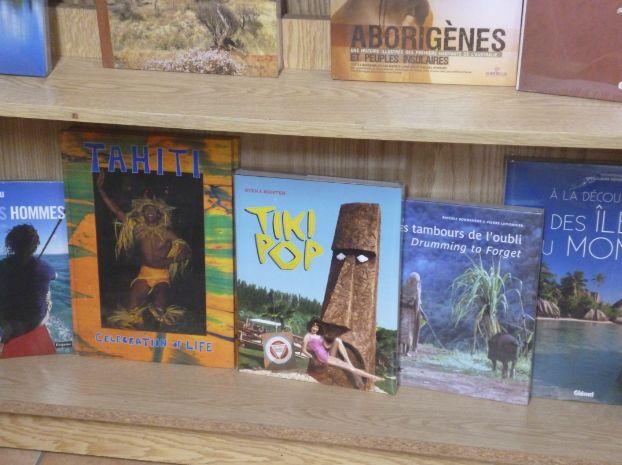

tiki pops up in all sorts of unexpected places, such as (on a small scale) on

the shelves of the Librairie Archipels bookstore:

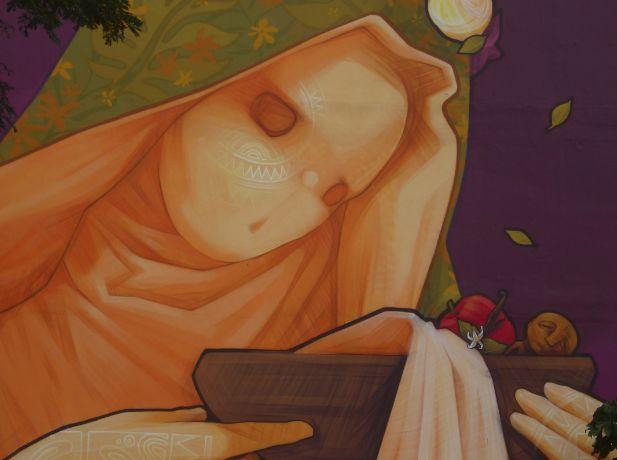

Or, on a

large scale, in a huge mural depicting a tatooed Virgin Mary on the Rue du

Général de Gaulle:

So, above

and beyond public statuary, the tiki is a vibrant symbol on Tahiti, featuring

prominently in commercial signage, architecture and public art.

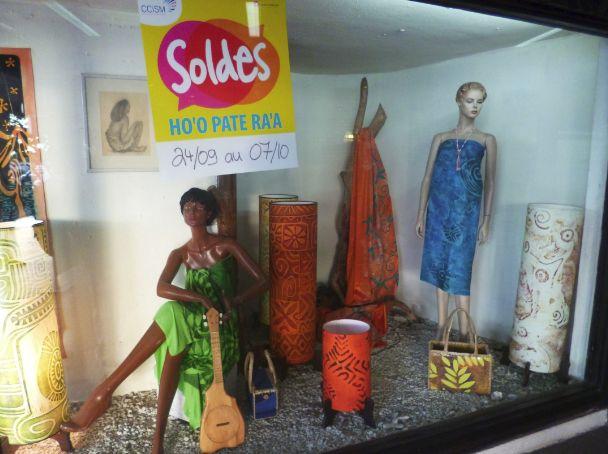

Tahitian

Style

Were

Tahitian style to be summarised in one word, it would perhaps be

"bright".

Trying to

find Tahitian clothing actually made in Tahiti is no easy accomplishment, given

that most of the fabrics and clothes sold in the shops in downtown Papeete are

made anywhere from Fiji all the way to mainland China. That island print fabric

you think is so delightful may have had to travel further to get to Papeete

than you did, and it is definitely a case of "buyer beware".

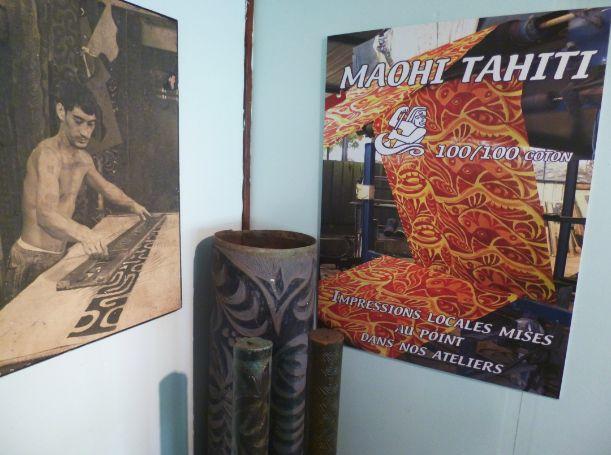

So it was

nice to see the Maohi Art Tahiti store (shown above) on Boulevard Pomare;

everything was made locally. In fact so locally it was only a few kilometres'

walk to their workshops, so I hiked out to Arue, east of Papeete, to have a

look at their operation:

The

turn-off, just before the Carrefour hypermarket on the main drag, is clearly

signposted.

That's the

side-entrance to the workshops...

This is the

screen-printing workshop where the clothes are made.

And there

was a clay workshop as well.

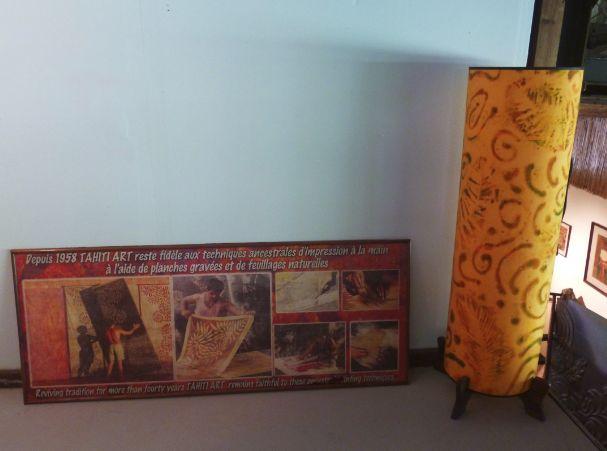

The firm

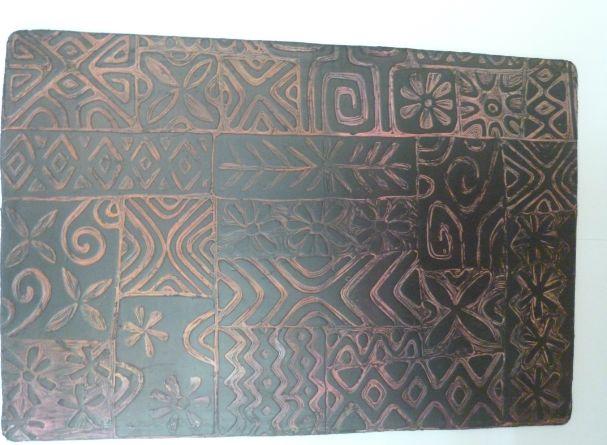

was founded in 1958, and features a small museum space for visitors to look at:

On display

is one of their earliest print patterns, cut into a 3 metre-long woodblock:

I couldn't

help but think that would look great on my tiki lounge wall...

They also

make these free-standing lamps with little wooden legs:

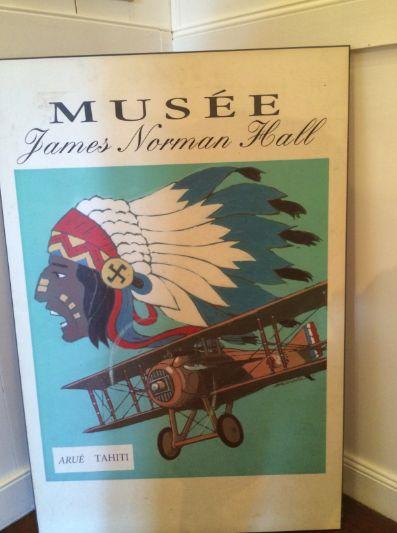

While I was

out in Arue, I took the opportunity to check out the home of James Norman Hall,

co-author of "Mutiny On The Bounty", among other books:

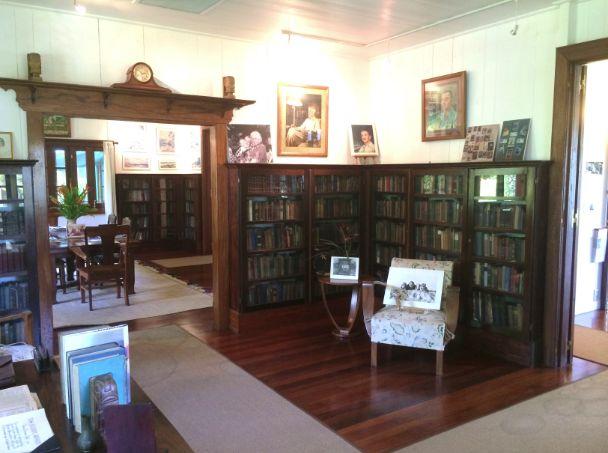

He moved to

Tahiti in the 1920s and lived in this home until his death in 1951. It was like

stepping back into another time:

His desk

(note the Marquesan tiki bookend):

The house

is full of the books that he had shipped at great expense via cargo freighter

from the United States, back in the days before Amazon.com existed...

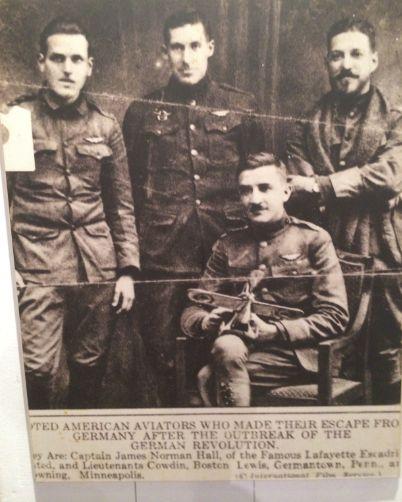

James

Norman Hall was an American of the same generation as Hemingway and, like

Hemingway, he volunteered for World War I at a time when most of his

compatriots were rigorously isolationist in their outlook. He signed up for the

British Army in 1914, spending 2 years at the front with the British

Expeditionary Force:

Clowning

around on a mule while he was with the 9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (he's the

one seated on the mule).

In 1917, he

joined the French Foreign Legion and was one of the members of the US Lafayette

Squadron:

He flew as

Eddie Rickenbacker's wing man, and shot down 4 German planes before he was

himself shot down over German lines:

He very

nearly ended the war in a German prison camp but, seeing the war was ending,

decided not to wait for repatriation and escaped to Switzerland:

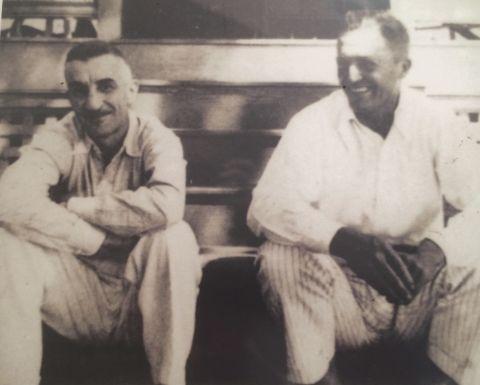

In the

early 1920s, he met another US veteran, Charles Nordhoff, with whom he wrote

the official history of the Lafayette Squadron, upon which they hatched a plan

to escape from civilization to live in the South Pacific as writers and

journalists. Hall with Charles Nordhoff in Papeete:

During the

1920s, they decided to write about a little-known incident in British naval

history that happened at Tahiti and the resulting trilogy on the HMS Bounty and

their subsequent novels made their names as two of the biggest-selling authors

of their generation, over a decade before James A. Michener wrote his first

book on the South Pacific.

So what has

all this got to do with Tahitian style? Visiting the home was a reminder of the

attraction of Tahiti for the world-weary, and James Norman Hall's great love of

the island shows through in his autobiography "My Island Home". He

admired the Tahitians for their love of life and humanity; a spirit that goes

beyond mere appearances and social formalities. My visit offered an example of

this and just why Tahiti is such a great place to live. Upon arriving, I was

greeted by one of the two ladies working there as guides and was given the

standard friendly welcome in French. Having been pointed in the right

direction, I then wandered around the house looking at the exhibits. I couldn't

help but overhear them talking in English to each other, so afterwards I headed

back to the cafeteria area at the back of the house where they were.

Reintroducing myself in English, I asked how come they were speaking in

English. It turned out that one of the ladies was born in Rarotonga and the

other one's father was Australian, so then it was their turn to ask how come I

was speaking in French when I arrived even though I wasn't French. Their jaws

dropped when I said I was from New Zealand (alas, too of my compatriots are

rigorously monolingual), but they were even more surprised when I said I had

walked from Papeete. Seven kilometres did not seem much to me but they

immediately offered me a free fruit punch and then another free one for the

road when they found out I was walking back to town too. As a parting gift, I

was also presented with a copy of James Norman Hall's autobiography "My

Island Home". What lovely ladies!

Strolling

along the main thoroughfare back to Papeete that Friday afternoon, feeling on

top of the world, and so glad I was in Tahiti rather than being stuck in my

office working, various people heading home waved and smiled at the sight of me

in my Hawaiian shirt and Panama hat, leisurely enjoying my fruit cocktail as

they rushed past in their bikes, scooters and cars.

And there,

standing on the side of the road, selling his catch of the day, was a guy who

really typified Tahitian style, even if he wasn't stylishly dressed:

A Day

on Moorea

The ferries

sail from Papeete's ferry terminal several times daily, starting at 6 am and

ending in the late afternoon.

Most

visitors to Moorea fly there, catching a domestic transfer directly from Faa'a

Airport once they arrive bleary-eyed from their long-distance international

flights. Although the flight, which takes only a few minutes, is convenient, it

is one of the worst decisions a traveller in French Polynesia can make. Nothing

can beat landfall on Moorea by sea, even if it is just via the ferry from

Papeete:

The 35

minute crossing is entrancing and Moorea looks magical. Your anticipation

builds as it gets closer.

My thoughts

went back to what various 18th-century French and English sailors must have

thought when they caught their first glimpse of the island after spending

several months sailing from Europe.

By the time

the ferry reaches the gap in the coral reef, the ferry port of Vaiare is

visible:

Many years

ago, I was told by a matriarch from Moorea that there is a legend concerning

the gap in the reef; if a young mother from Moorea brings her newborn baby home

to the island from Tahiti or abroad for the first time, she will watch the

water anxiously to see what accompanies the ferry: if she sees sharks following

the vessel, the baby will have a cursed life; if she sees dolphins leading the

vessel, the child's life will be blessed. I knew she had spent most of her life

working away from her home island, so I asked what had happened to her. She

smiled and said she had seen dolphins.

The ferry terminal

at Vaiare is a lovely old wooden building. You can get rental cars in Vaiare

but it pays to book in advance. I was hoping for a rent-a-bike outfit, but none

was visible during my short stroll up and down the main drag. On the topic of

drag, I was mooned by a teenage mahu (transexual) while I was taking this

panoramic shot from the wharf:

I was using

an iPhone to take my panoramic photos, and you basically hold up the camera,

press the button and rotate on the spot until you have taken your photo and

press the button again to stop. Fortunately I caught sight of the offending

rear end (to the right of the white post) out of the corner of my eye before

the camera caught it for posterity.

Moorea is

roughly 60 kilometres in circumference, and so you need some sort of transport

to get around. Quickly putting my phone away and ignoring the cackling mahu, I

traipsed back to the ferry terminal where there were a couple of taxi vans. In

the back one, an elderly Polynesian fellow was chatting to an elderly European

(Popa'a) lady in the back seat. I asked in French if he was free and, much to

my surprise, the lady (who I thought was his fare), hopped sprightly out of the

back seat and led me to the front van.

She was

surprised when she found out I was from New Zealand given that I was talking to

her in French but she soon got over it. I explained I wanted to head up to the

Belvédère (look-out) above Opunohu Valley, on the northern side of the island,

and have a look at the marae site up there too. No worries!

I was

momentarily distracted by this concrete triceratops on the roadside as we drove

to Opunohu Valley. My driver's name was Elisabeth, and it turned out the man

she had been chatting to was her husband, still working at the age of 82. She

was in her 70s and she told me she had moved to French Polynesia when her

parents decided to leave her homeland of Switzerland when she was a little

girl. This was at the time of World War II and it was clear from what she said

that her parents had decided that bringing up their children (her and her older

brother) on Hitler's doorstep was not a desirable option.

So while

war raged in Europe, they settled on Moorea, and bought land in the Opunohu

Valley, not far from the legendary Cook's Bay, where Captain Cook moored his

ships during his voyages around the Pacific in the 1770s:

The peak in

the middle of the photo is known as the "Sacred Mountain" in Tahitian

and is a burial place for countless generations of ancestors, with bones being

interred in the nooks and crannies all the way up to the top. Consequently it

is tabu, and it is forbidden to climb on it.

Elisabeth

had spent her entire life on Moorea and had never been back to Switzerland. She

explained she had travelled to Bordeaux to visit her daughter once while she

was a student in France but she hated it; it was too cold. She said she liked

New Zealand better and had been there three times. She had been working as a

taxi driver for many years and had fond memories of shuttling around the stars

of the 1984 version of "Mutiny On The Bounty", saying Anthony Hopkins

was a charming man, as was Mel Gibson. As she also recalled the arrival of the

crew and cast of the earlier 1962 version, I asked her about Marlon Brando, but

she was not willing to talk about him for some reason...

We were just

driving up the Opunohu Valley when she suggested a detour to the left to visit

the local distillery - Hell yeah!

The Manutea

Distillery is not particularly photogenic, but the visitors' centre and shop

does have a nice looking tiki to greet visitors:

I partook

of a free sampling of various products at their bar, including the classic

"Tahiti Drink". God bless them; it's Mai Tai in a cardboard milk

carton!

I had

actually had this stuff before and while it is not as good as the real thing,

you can't beat it for convenience, and you've got to love a place where you can

buy bulk Mai Tai from the corner store cooler.

I also

tried the new formula Tahiti Drink, but it didn't do it for me. Then I

proceeded to bore poor Elisabeth and the bar lady by pointing out that the Mai

Tai was from Oakland, not Tahiti. They took it gracefully...

Here's

their Website for further information:

And Manutea

has a Californian distributor:

http://enchantedisleusa.com/?age-verified=751384a5d2

Quite

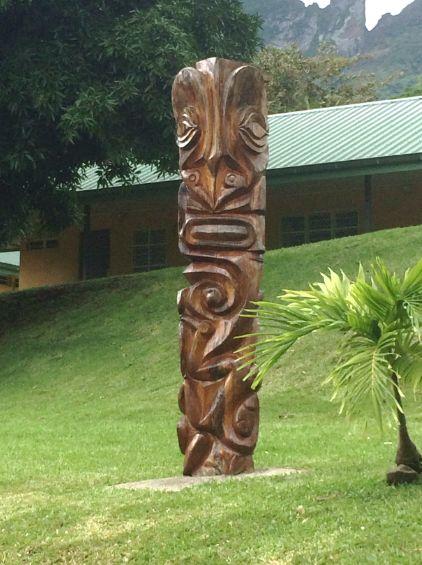

relaxed after the free drinks and having bought some liqueurs (I recommend

their banana liqueur), we climbed back in the taxi van to head up to the

look-out. On the way, we were zooming past the territorial agricultural college

when I yelled out to Elisabeth to hit the brakes. I even had the temerity to

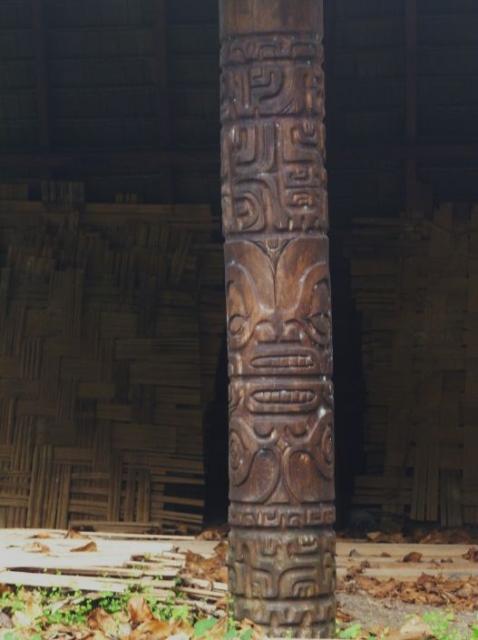

ask her to back up a bit so I could bet a better shot:

A very fine

piece of carving, about 2 metres tall, with a Pop Art twist - nice!

The

"Lycée Agricole", as it is known in French, draws students from all

over French Polynesia. One of their major challenges is how to grow usable and commercially

viable exotic timbers for construction and various domestic uses. The problem

with growing trees in that climate is that the wood gets very knotty due to

rapid growth in the tropical heat. Elisabeth pointed out to me that a good many

houses on Moorea were built from timber that had been shipped from as far away

as Australia and there were major development stakes involved in French

Polynesia being able to set up its own sustainable forestry.

A few

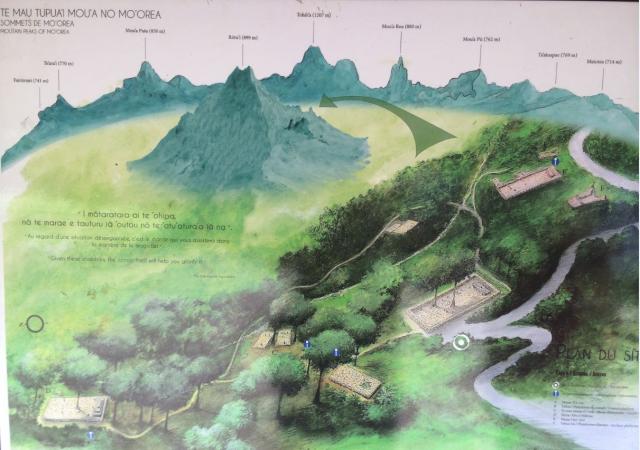

minutes later we reached the look-out, which offered an unbeatable view of the

northern end of Moorea:

Opunohu Bay

is to the left, with Opunohu Valley in the foreground, the Sacred Mountain is

in the middle, and Cook's Bay is to the right.

While we

were up on the heights, Elisabeth told me about how, shortly after her family

arrived in Opunohu Valley, back in the 1940s, her father told her and her older

brother to go out looking for eggs - he was hoping that some local ones would

be edible. Up in the hills, her brother found what he thought was a monkey

skull in a crevice under a large rock, so he brought it home to show his

father. When he was informed by his father that there were no monkeys in French

Polynesia and that the skull he was holding was human, he dropped it onto the

floor and it shattered into little pieces. His father visited the local metua

(tribal elder), presented the remains and explained the situation. He was told

not to worry as the skull had been found on was on land that was not tabu and

that there were a lot of dead people up in the hills whose origins were

unknown. Nevertheless, Elisabeth's brother took fright and would not go out at

night for many years afterwards.

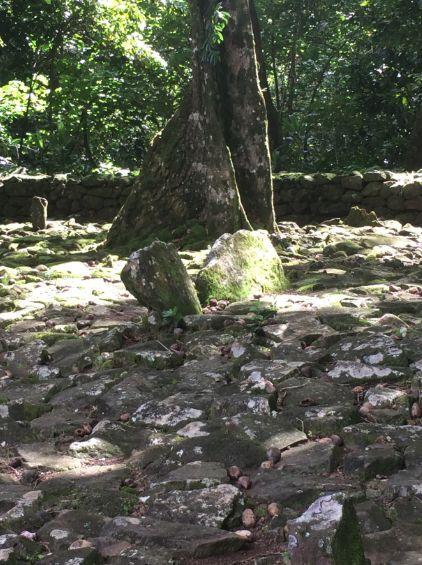

We then

drove back down the road to visit the pre-European marae site. Maraes in this

part of the world are quite different from the ones I have visited in New

Zealand; nowadays they are meeting places for the community to gather. In

pre-European times in the kingdom of Tahiti (Moorea was one of its dominions),

maraes were gathering places for the upper class; the aristocracy, priests and

their attendants. They were also places of horror.

At the top

of the site were archery platforms (archery was a sport restricted to the

aristocracy), while the main platform with the white circle beside it was where

sacrifices were made to the gods.

Elisabeth

enjoyed pointing out all the gruesome little details to me. Here is where the

sacrifices were made:

Each

sacrificial victim was forced to kneel and place his or her head in-between

these two stones:

Once

beheaded, the victim's head was placed in this trough for the blood to drain:

Although greatly

romanticised by Europeans when first visited by French and British explorers in

the 18th century, the societies of Tahiti and its various islands were not as

idyllic as Diderot and his ilk imagined.

Elisabeth

also took me down the hill to the most secluded part of the site; the platform

where the chiefs and priests held council meetings:

On the way

we passed a dodgy-looking crew of young Moorean guys, sitting around a smokey

fire to ward off the nonos (mosquitos). Elisabeth said something to them in

Tahitian which made them all sit up with a start as we passed. Not choosing to

translate for me, she waited until we were out of earshot and then quietly said

to me in French: "Don't turn around but I bet those two big sacks they

have by that fire are full of harvested dope." She was a feisty old gal!

I said

farewell to Elisabeth when she dropped me off for lunch back in Maharepa, not

far from Cook's Bay.

After

lunch, I took a moment to photograph one of Moorea's most distinctive features:

That's not

a tree; it's a cell phone tower. They ring the entire island and blend in

nicely, offering an example of French engineering ingenuity and a lesson in

environmental friendliness for various telcos the world over.

The café

where I dined had this tiki nearby:

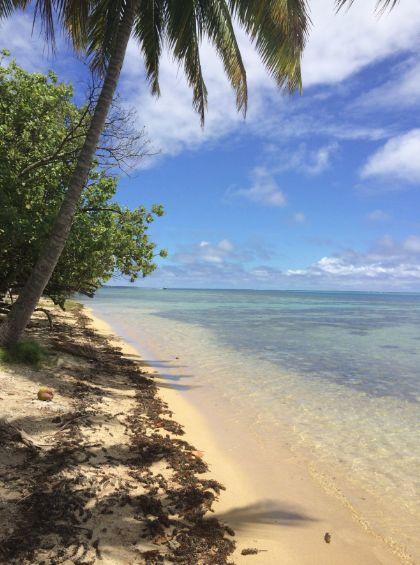

I then went

and relaxed on the beach for a while:

The beach

was quite lovely, but was quite small, only being a kilometre or so long. It

also happens to be the only public beach on Moorea. All the rest of the coast,

all 60-odd kilometres of it, is private land. One of the blessings of growing

up in New Zealand is the legal concept of the Queen's Chain, which basically

states that coastline is public property. Unfortunately no such distinction exists

under French law, and private landowners blocking access to beaches is a curse

throughout various parts of France and its overseas territories.

Still

having plenty of time, I wandered back up the road a couple of kilometres to

Cook's Bay to visit a derelict hotel Elisabeth had pointed out as the oldest

one on the island:

I was

magnetically drawn to the place and had no compunction about trespassing.

Elisabeth had said the hotel dated from the mid-20th century and I knew I would

find some there. Sure enough:

Tiki

Island!

The tikis

at water level had seen better days:

The pink

ones on land were in good condition though:

Although

some were getting their view obscured by encroaching greenery:

While not

exactly authentic, these gaudy pink Marquesan-style tikis are probably some of

the oldest ones on Moorea.

The hotel

has gone through three failed attempts to revive it, but the competition from

newer resorts just up the road proved too stiff. It looked like various people

were squatting in the hotel so I did not bother trying to snoop around the

building itself.

I also

cheekily invited myself in for a quick look at the competition back in

Maharepa; Moorea Pearl Resort and Spa:

The toilets

were very well-appointed:

And

featured their own welcoming tiki:

I paused

for a brief rest but did not stick around as I noticed one of the desk staff

was looking quizzically at me. Having already once been escorted off the premises

by security for gatecrashing Club Med Nouméa many years ago, I did not want

history to repeat and headed back to the road.

I walked

most of the 15 kilometres back to the ferry terminal, pausing to take a few

photos on the way. This is the cheapest stilt hut tourist accommodation in

French Polynesia, just a few kilometres north of the ferry terminal:

As I

walked, I contemplated what Elisabeth had told me about how much the island had

changed during her lifetime. Although those huts are pretty, they do not look

local. She told me there are only two traditional style huts left on the

island. Nowadays most of the houses are in a Mediterranean, Spanish or even

Swiss style. Moorea still remains a strikingly beautiful place though.

Tahiti, as seen from Moorea.

Welcome

to the Marquesas: Nuku Hiva

Air Tahiti

provides a map specially for Europeans who complain about its high domestic air

fares: in order to show them the distances involved in travelling around the territory,

it features French Polynesia superimposed over a map of Europe, with Tahiti

positioned where Paris is. On this map, Nuku Hiva is positioned inland from

Stockholm. Flying there from Papeete by a twin-engined propeller aircraft takes

about four and a half hours, crossing a vast expanse of deep empty ocean.

Nuku Hiva

appears as a dot on the horizon, and then gradually takes form to the extent

you can see its only airstrip, in the windswept north-eastern part of the

island known as the "Terre Déserte" (the Desert Land). From the air,

Nuku Ataha airport looks like it is clinging to the side of island:

From the

tiny airport terminal, it is over an hour's trip in a four-wheel drive vehicle

to Taiohae, the administrative capital of the Marquesa Islands. The 4WD's are

no longer as necessary as they used to be as sealing of the road crossing the

island was completed in 2013. Prior to that though, the old dirt road was

subject to slips and flooding when it rained.

The trip

over the Toovi Plateau was an eye-opener for me: it was like being back in New

Zealand. Not only did the temperature drop to a level comparable to New

Zealand, the landscape featured pine trees, cattle and horses:

The French

Admiral Dupetit-Thouars brought horses to the island from Chile in 1842,

continuing the Marquesas' long history of interchange with Latin America dating

back to 1595, when the Spaniard navigator Alvaro de Mendaña y Neira first

sighted the archipelago and gave it its European name.

Once the

road started winding down the other side of the island, Taiohae came into view;

a town with around 1,700 inhabitants, scattered along the inner rim of a

flooded extinct volcano, providing a natural deep-water port:

Once I had

dropped off my gear at the B&B I was staying in, I went for a stroll along

the bay. The pace along the waterfront was much more sedate than in Papeete:

But there's

more to Taiohae than just sand, horses and coconuts:

Indeed, as

we will see, given the number of statues there, it might more appropriately be

called "Tiki Central"....

But that had

to wait for the time being, as I was thirsty and it was lunchtime:

Taiohae

- A Tiki Tour: Part 1

This fine

family grouping of Marquesan tiki folk sits outside the Fare Artisanal (Crafts

Centre):

The mamma

tiki seems to be changing the baby while dad and the kids provide a shield...

The Fare

Artisanal is a great place to get carvings: I was so overwhelmed at the high

density of cool stuff I completely forgot to take a photo of the interior while

I was buying things there.

Behind the

Fare Artisanal is the town market, one of the few areas in Taiohae that is

well-lit at night, thanks to these individuals holding up the lamp posts:

Girl and

guy versions.

If you do

intend to wander around Taiohae at night, take a flashlight as, like most

places out in the islands, street lighting is not a high priority.

The market

entrance. This post looks like wood but is in fact painted concrete:

And in case

you want to deck out your slippery tiki bar floors with appropriate safety

signage in Marquesan, the caption reads "Tohua peeno" (slippery

floor).

The market

has a colourful garden:

With these

guys as the centrepiece:

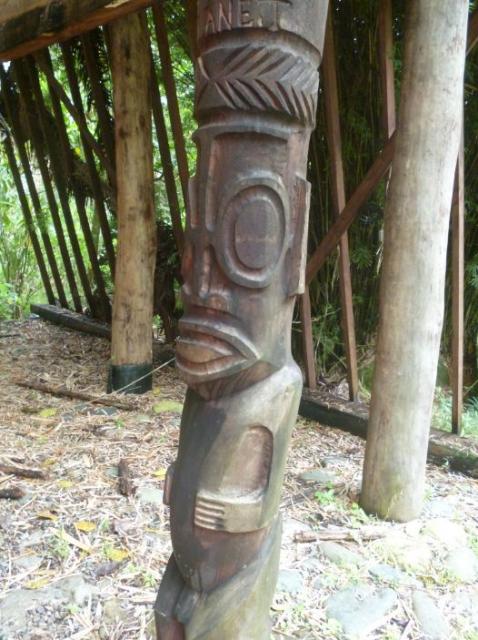

And with

this guy lurking in the foliage nearby:

And this

guy facing them, near the Fare Artisanal:

Beyond the

market place, there is a wharf with a few shops, including a yachties' supply

store. Its posts are real wood:

Nice use of

found materials. Close-up:

Up the hill

from the market is the Vallée des Français, which is where the first French

settlers lived, and is still the site of various administrative services. Back

in the day, this fine piece of colonial architecture would have been the

headquarters of the local French colonial administrator; nowadays it is the

office of the Marquesas Sub-Division of the Territorial Government of French

Polynesia.

Blink and you

would miss them, but I was paying attention: outside this 19th century piece of

colonial architecture are some small but old and weathered tikis:

Behind the

market and up the hill a bit is the local cemetery. Given the Catholic Church's

traditional antagonism towards pagan symbols and its local representatives'

historical penchant for destroying, defacing and emasculating tiki carvings, I

was not optimistic about finding any tikis there but, lo and behold, however

stylised and unobtrusive, there was one:

Climbing up

to the top of the Vallée des Français, I spotted this tiki, boxed in alongside

a garage - perhaps to deter thieves, or maybe to stop him falling over? (he

does look a bit top-heavy)

Walking

back along the waterfront, the promenade is practically lined with tikis. This piece

was intriguing:

It was here

that I was first tooted by a passing pick-up truck and people waved at me as I

was taking photos. Over the next few days, various locals noted my documenting of

their tikis and were very welcoming as I did so.

The local

Air Tahiti office a bit further along the waterfront has tikis outside its

entrance, looking weather-worn and mossy:

And the

Banque Socredo has tikis to greet its customers:

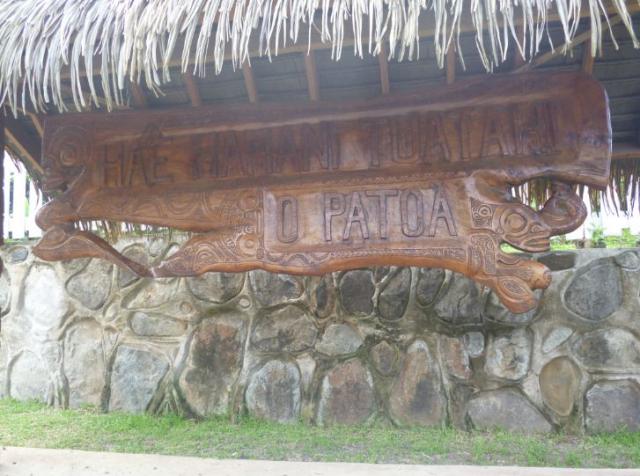

Beyond the

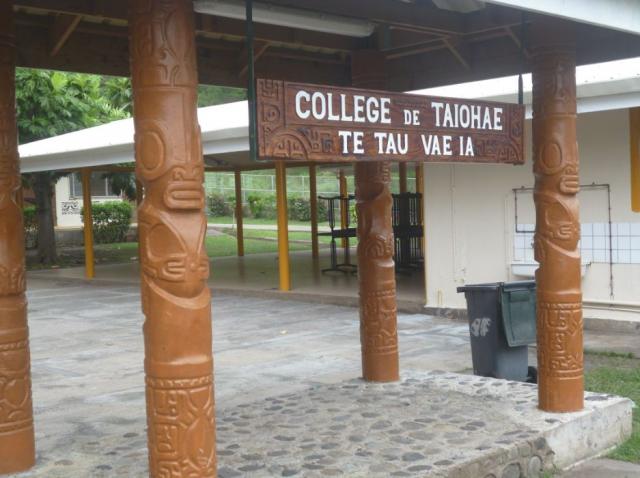

bank, a bit up the valley, is the local high school or lycée:

Detailed

views of the sign:

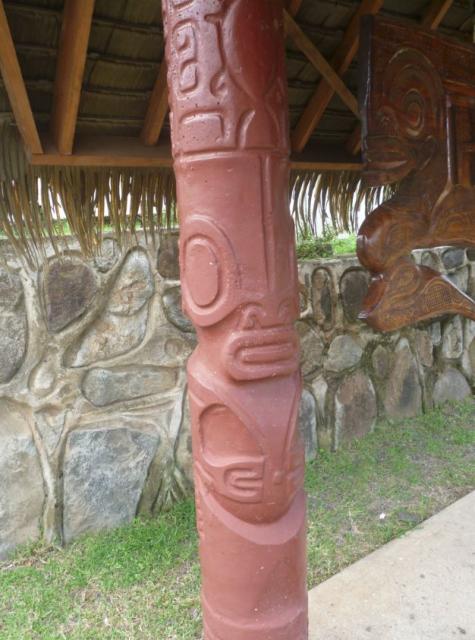

The sign is

housed in a structure supported by concrete posts - front and rear views:

And beyond the

high school is the pétanque facility:

Well that

covers the first 800 metres of our tiki tour around Taiohae. As you may have

noticed by now, the town has more tikis than you can shake a stick at.

Our next

stop is a visit to the Temehea historical site, just a bit further along the

waterfront:

Taiohae

- A Tiki Tour: Part 2

The best

time to visit the Temehea site is at night, preferably a cloudless one, with

the stars and the moon providing natural lighting, and the rhythmic sound of

the waves crashing on the adjacent breakwater providing the sole reminder of

the passage of time.

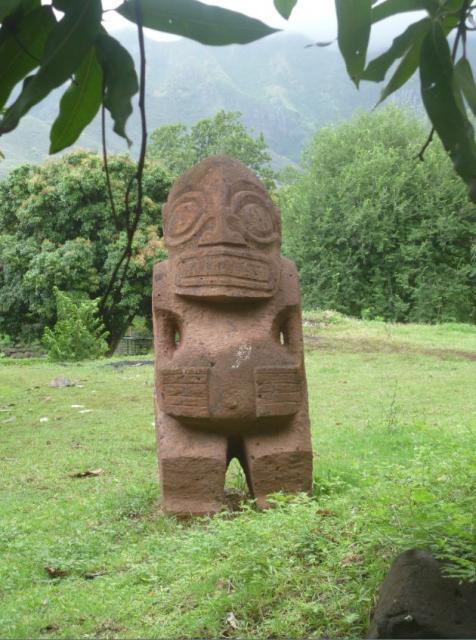

This me'ae

(Marquesan for marae or meeting place) is where the Nuku-Hivans had their first

contacts with Europeans in the late 18th century. These included William Crook

from the London Missionary Society, the first missionary to land on the island

in 1797. E. Roberts, the first beachcomber to arrive on the island, was also

formally accepted by the local chief there as part of the traditional haaikoa

or name-exchanging ceremony. Unlike the good Reverend Crook, Roberts was also

awarded the chief's sister as a sign of friendship. And in 1804, the Russian

captain Von Krusenstern landed here as part of his trans-Pacific explorations.

In an incident reminiscent of the HMS

Bounty, his crew mutinied during that visit. During the War of 1812,

Captain David Porter of the US Navy and a small flotilla called in here to

claim Nuku Hiva for the United States in 1813. A brief and bloody colonial war

broke out in response to this first American land grab in the South Pacific

which ultimately proved fruitless as Congress refused to ratify the seizure and

Porter was subsequently defeated by the Royal Navy in the battle of Valparaiso

in 1814. The site survived these various events, only to fall derelict from

1901 onwards.

In 1989,

for the 2nd Marquesan Festival of the Arts, it was decided to renovate the

site. Two master sculptors, Uki Haiti and Kahee Taupotini, carved most of the

new sculptures visible, reflecting various aspects of Marquesan life.

The paepae

is an open-sided structure that was common in pre-European times both for homes

and for platforms where chiefs sat with their councils. The one at Temehea was

completely rebuilt and extended from the late 1980s.

In a

central location is a large plinth marking the rebirth of the site:

And

standing atop it is this well-endowed traditional-looking fellow:

Although

some busy-body christian has emasculated this poor headhunter tiki:

A detailed

shot of the severed head he is carrying:

In front of

the chief's paepae is the local tikis' very own miniature paepae:

It provides

a wonderful set of caricatures of tikis at a tribal gathering, giving play to

their varying emotions as they sit and watch the proceedings:

In the

front row, the tiki on the end is just sitting stony-faced, while the others'

body language is saying things like "He said what?!?" "Oh my

God!" "Nope, I ain't impressed with that..." This is the level

of carving caricature and social commentary that you would more expect to see

on the walls of a European Medieval church.

Then there

are these figures looning around on the roof for light relief - one of them

seems to be a horse...

And around

the side are the women and children, wondering just what the outcome of this

meeting is going to be.

Not all of

the sculptures are local. This one is from Easter Island, and celebrates the

links between Easter Island and the ancestral homeland of its people; the

Marquesas.

This

carving, on the other hand, cocks a snoot at Tahiti:

In the

1980s, the Tahitians succeeded in getting up the Marquesans' noses on various occasions,

particularly when Tahitian elected representatives in the Territorial Assembly

attempted to make Tahitian the official language, to be taught in all schools

across French Polynsesia. In 1983 (as I recall), a Marquesan Territorial

Councillor stood up and delivered a fiery speech basically telling the

Tahitians what he thought of them for being so presumptuous as to assume

Marquesans would abandon their own language to speak Tahitian. It was the

starting point for the cultural renaissance that resulted in this site being

restored. So here is Uki Haiti's masterful caricature of a pot-bellied, pompous

Tahitian, strutting in a wig and pretending to be Marianne (the symbol of the

French Republic and Jacobin centralisation).

This

sculpture provides a contrast, showing the united nature of Marquesan tikidom,

working as a community:

That wraps

up the brief tour of the site; excuse me while I pop off to the nearby corner

superette for a quick refrigerated drink...

... before

we proceed on to the local museum, and Nuku Hiva's only tiki cocktail bar and

restaurant.

Taiohae

- A Tiki Tour: Part 3

Wandering

around to the western end of Taiohae Bay, we pass by the local intermediate

school, which features more concrete tiki poles.

The tiki in

the courtyard appears to be a mother pushing her unwilling child off to school.

![]()

Our first

stop is the Hee Tai Inn, which features some nice awning poles hidden around

the back of the building:

Note the

thatch; I'll come back to that later...

Having seen

so many concrete posts, I initially thought these ones might be concrete too,

but they were painted wood.

The Hee Tai

Inn is run by Rose Corser, an American lady who has amassed quite a collection of

Marquesan artifacts over the years and who has set up her own small museum in

an annex to her office.

She has

rescued various small stone tikis from the ravages of the local climate, and

they are now in cases in her climate-controlled museum:

She also

has various wooden tikis in her collection:

As well as

various traditional weapons:

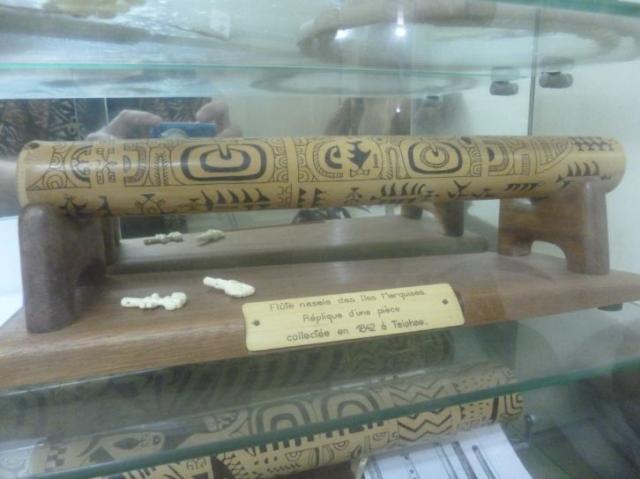

I was

particularly fascinated with her collection of nose flutes, which were

reproductions of pieces from the 1840s, the originals of which are held in a

museum in Paris:

Not much is

known about pre-European contact Polynesian music, and I attempted to ask her

about these flutes and precisely how they were played, but seem to have hit on

a sore point or something and she went off in a huff. She brightened up when I

subsequently purchased some carvings off her though. I seem to have caught her

on a bad day as she had earlier greeted me with the comment "I hope you're

not going to complain about the lack of captions in English". I replied

that as French was my second language that would not be a problem. It was an

odd visit, but she does have a good collection and it is worth a look.

If you

follow the dirt road that arcs up the hill behind the Tee Hai Inn, you will

soon arrive at the Keikahanui Nuku Hiva Pearl Lodge:

Inside is

Nuku Hiva's best bar and restaurant:

I kept

coming back to this place for lunch and dinner as they do very good cocktails

and the food was wonderful too:

Apologies

for the loss of focus on that one but I was on my third drink by that stage...

The view of

Taiohae Bay was great too:

Up over the

hill from the Pearl Lodge is a winding road that leads to Colette Bay.

Unfortunately it is not signposted, and features numerous dead-end turn-offs. I

got to the summit on the third try. The view looking back on Taiohae Bay:

Colette

Bay:

The hills

around the bay are quite bleak and rugged and reminded me of Bank's Peninsula:

Although

there are a couple of homes nearby, the beach was deserted apart from this girl

who came out to say hello:

This is

also where Survivor Marquesas was filmed, so I was curious to search for the

site where they filmed it. I did not have to look far:

A big

swathe of sand cutting right across the middle of a stony beach. It looks like

the sort of thing they would have done for TV...

Following

the swathe of sand inland I found a stone marking a meeting place and a pile of

rubbish left behind:

The remains

of an overgrown firepit filled with plastic bottles:

Most of the

site was overgrown with new saplings:

It is

ironic that one of the big claims made by the makers of Survivor Marquesas is

that the people in it were roughing it, struggling for survival on some godforesaken

island in the Marquesas. In fact, they were only half an hour's walk or ten

minutes' drive from the best bar and restaurant in the archipelago, and

Taiohae, the islands' administrative centre, with its various shops and cafés.

So much for reality TV. ![]()

In the next

instalment, we push inland, up behind Taiohae, to explore the Pukiu Valley....

The

Road to Tohua Koueva

The road of

up Pakiu Valley featured various things that caught my eye, including this

crumbling old paepae, which nonetheless had some very nicely executed carvings:

Another

structure that caught my eye was this traditional house:

With its

shutters, high ceiling, and air space under the eaves, it shows what houses in

the islands looked like in the early 20th century and was one of the very few

homes of this kind I saw while I was in French Polynesia. These days, homes in

Taiohae are built from concrete with glazed windows, aluminium joinery, air

conditioning and so forth.

I noticed

there were a few large stone tikis on various properties as I headed up the

valley:

The

turn-off is unprepossessing, but it is signposted:

Before

long, I came to a ford over a stream, along with two pigs and a cock:

This pig

was very friendly and was clearly hoping it was feeding time, but he was

tethered to a post so did not get to say hello.

I got a bit

wet and muddy crossing the ford, but with scenery like this, who cares?

There were homes

tucked away in the trees, and shortly after taking this photo I was stopped by

a woman who popped out of a gateway and asked if I was going to Tohua Koueva.

When I answered "oui", she warned me not to miss the turn-off to the

left a hundred metres up ahead where there is a banyan tree as it was

unsignposted. I thanked her and went on my way. As I was struggling up the

muddy slope I heard her turn to her husband and say "wow, that Hawaiian

guy is really tall!" I am 6 foot 1, but as I was only wearing a red

Hawaiian shirt, I am not sure that makes me a Hawaiian. ![]()

There was

the banyan tree, as the lady told me:

I said

"bonjour" to the grazing horse giving me a sideways stare as I took

the turn-off.

Before long

I was at the site's entrance, where I said "bonjour" to the two

groundsman cutting the grass with scrubcutters:

The

signposts were nicely carved:

Just beyond

the gate was this stone fellow with an odd expression:

Soon the

first of the site's reconstructed paepaes was visible:

Tohua

Koueva was a substantial site of habitation, being the base for the war chief

Pakoko until 1845, when the French raided it, killed him, and the site was laid

waste, eventually returning to the jungle and becoming overgrown. As part of

the Marquesan cultural renaissance that occurred from the 1980s onwards, it was

resurrected and painstakingly cleared and restored for use as a cultural site,

and is where Nuku Hiva's biggest festivals are held every other year,

attracting dance troupes and other traditional performers from far afield.

All of the

structures and carvings on the site are contemporary.

This paepae

shows the need for rethatching every few years that is a necessity with

traditional roofing materials due to the island's humid climate:

What really

caught my eye was the cute little guy to the right:

Although

the paepae's posts were noteworthy too:

Other

paepaes had their thatch intact:

Closer

examination showed that the thatch actually consisted of strips of recycled

plastic material.

This paepae

looked like it was still being built:

There was a

higher level terrace up behind these stone walls:

Time to

explore...

This is the

main performance area when the cultural festivals are on, with a large banyan tree

down one end providing the focal point; people sit in these paepaes:

Under the

plastic thatch, the posts on them feature a range of styles:

Beyond the

performance area was an isolated paepae that drew my attention:

It was

sheltering various works-in-progress, although I did a real double-take as I

drew closer to the central stone carving by the steps:

It's Gollum

from The Lord Of The Rings! Proof that Marquesan carving styles are not

standing still and local carvers are seeking inspiration in unlikely places....

A close-up

of a couple of posts still being worked on:

Down the other

end of the performance area, I found this lonely stone tiki:

Being

exposed to the elements, he had gone quite mossy:

Like this

Easter Islander across the way from him:

It was a

very peaceful location and I sat for a while taking it all in while I had a

drink.

As

lunchtime was approaching, then it was time to head back down to the bay

through the passageway between the stands:

In the last

instalment, we travel to the most remote parts of Nuku-Hiva: Taipivai, Hatiheu,

and beyond...

Taipivai,

Hatiheu, and beyond...

On the

northern side of the island of Nuku Hiva lay further places for exploration,

the most famous of which is Taipivai, known to the world through Herman

Melville's stay there in the 1842 after he jumped ship. I was wondering what to

expect when I arrived there. Would it be a tranquil deserted wilderness like

this:

Or would it

feature a dusky maiden lazing around just waiting for me?

Or even a

whole bevy of them?

Or might

the reaction be somewhat hostile, given the long history of European incursions

into that valley?

As it

turned out, the first image was the one that best matched what I actually saw:

Controleur

Bay, and below is the seaward end of the village of Taipivai, which stretches

up the valley:

The effects

of the tsunami off Japan that caused the Fukushima disaster on 11 March 2011

were felt as far away as Taipivai: according to my guide Yvon, who is from

Taipivai, a small tidal wave washed up onto the beach here and destroyed

several houses. Some of the families that lost their homes chose to rebuild way

up the top end of the valley rather than face that experience again.

We were to

return to Taipivai on the way back. Our immediate destination was in the next

valley over, on the northern coast; Hatiheu:

As we descended

into the valley in Yvon's Landrover, he told about the arrival of the first

European missionary here in the 1830s, who disembarked in the middle of a blood

feud in which the various inhabitants of the valley were killing each other.

For his own protection, he decided to scale the lowest pinnacle to the left of

the bay and take shelter there. To while away the hours, he began carving a

stone statue of the Virgin Mary. Curious, various locals began climbing up the

sheer rock face to ask him what on earth he was doing, and that was the start

of the valley's conversion to Christianity.

The statue

is still there, and is just visible in this photo taken from Hatiheu, to the

right of the two trees in the middle of the rock:

However

Hatiheu was not our destination either, we were hiking over the hill to Anaho

Bay:

Accompanying

us were a French couple on their 50th anniversary holiday. I was somewhat taken

aback at the amount of equipment they had with them: fancy hiking boots, the

latest outdoor wear and backpacks; they even had those hi-tech composite

walking poles so beloved of Europeans when they need to stride over any

landform that veers slightly away from horizontal. On top of that, Yvon let

slip that he was a fireman with outdoor rescue training who had done the

coast-to-coast Ironman race from the West Coast to Greymouth. So just how tough

was this trail going to be? I only had street shoes, my Fijian tapa-patterned

shirt, a Panama hat and my 1980s vintage UTA travel bag with a bottle of water

and some biscuits as my sole resources. Hmm...

On the

uphill stretch, it turned out that my main worry was not the severity of the

terrain, but the harshness of the the misandrist ramblings of the French wife,

who, in the company of three men, ventured to have a go at her husband because

he was reluctant to wander just off the steep trail and do number 2s as there

was a group coming up the trail behind us: she took this as a cue to start

pontificating about how useless men were without a wife to make decisions for

them. I replied in my most insouciant French that I had been a bachelor all my

life and had managed to get by alright thank you very much, which drew a pained

"please don't provoke her" glance from Yvon while he tried to veer the

conversation onto another course.

Anyway,

this was the view from the summit:

That's

Anaho Bay to the left, with a bit of Ha'atuatua Bay visible to the right.

By this

stage, I had worked up a mild sweat, but the French couple were looking a bit

shaky on their walking poles, and the wife was gasping for breath, so we were

thankfully spared of any further pearls of feminine wisdom. The plan to walk as

far as Ha'atuatua Bay was also shelved; it looked like the couple would only be

able to manage the 30 minute walk down to Anaho Bay.

As we

descended down into the valley, Yvon pointed out an abandoned paepae that had

once been a family home:

Just below

it was the more modern abode that had replaced it:

The sun was

out by the time we got down to the beach and stopped to suck on some mangoes

Yvon had brought along:

Anaho Bay

is strikingly beautiful:

Little

wonder that Robert Louis Stevenson praised it when he sailed through these

parts in 1888.

We then

wandered along the beach to visit the local priest who was in the middle of a

coaching session with local kids preparing for a cultural performance:

I had a

quick peek in the chapel nearby:

Along the

beach and further up the valley were stands of coconut trees:

Amidst them

was a copra shed, with sacks full of harvested coconuts waiting to be picked up

and shipped off:

Toiling

back up the trail to return to Hatiheu, we crossed paths with a young man

bringing down coconuts from the back of the valley on his horse:

As the path

got steeper, the puffing and wheezing grew louder from the couple, and we had to

stop from time to time so they could catch their breath. The wife by this time,

was most insistent that I walk ahead of her, until we reached the summit and

the downhill stretch, when, like a magificent butterfly, she metamorphosed into

a pole-wielding speed fiend, hell-bent on arriving back at the Landrover first,

if only to prove her earlier oft-repeated point that while she was slow uphill,

she was very very fast downhill. As we climbed back into the Landrover, from

his expression, I could tell Yvon was thinking much the same of her as I was.

Never mind, lunch awaited us back in Hatiheu...

The Hinako

Nui café was on the waterfront and offered a pleasant view:

And a few tikis:

Along with

a nice fish platter:

While a

chook strolled around under the tables:

The French

wife was by this time indicating that it might be better to call it a day after

lunch given how tired she was now feeling, but I was having none of it. I

replied that I was feeling fine and was looking forward to the rest of the day:

this trip was a two-for-one deal, and the agreement was that in exchange for

hiking over hill and dale in the morning, the afternoon would be spent visiting

the biggest pre-European archaeological site on the island, along with a visit

to admire all the tikis at Taipivai's marae.

I started

by taking a few photos of the tikis along the waterfront in Hatiheu:

So off we

went, with the grumbling French wife in the back seat complaining about the

heat and how tired she was. Not quite the female reception I had hoped for on

this trip...

Nuku

Hiva: Past and Present

We arrived

at the site of Kamuihei, Tahakia and Te'i'ipoka just as some stud farmers from

Taipivai were rounding up their grazing horses to herd them back up the Hatiheu

valley road and over the hill to Taipivai. They give a good idea of the massive

scale of the stone construction at the site, all done using just levers, ropes,

and a lot of sweat.

The three

adjoining sites had a total population of around 3,000 in pre-European times,

and the oldest structures there date back 600 years.

Kamuihei and

Te'i'ipoka are on this side of the road in the photo above, taken looking

southwards, while on the other side of the road lies Tahakia. It was difficult

to take a single photo giving an idea of the lay of the land, as the site is so

large.

The photo

above, taken facing northwards, shows some of the Kamuihei site, while

Te'i'ipoka is beyond.

I wandered

back down the road towards Hatiheu to have a look at a reconstructed paepae:

On the

Tahakia side of the road, this rustic-looking tiki stands guard:

Further on,

a log bridge leads to the Tahakia site:

The

settlement used to have its own water supply in the form of this stream, now

long dried up:

Tahakia

takes the form of a long rectangular arena, overlooked by higher platforms:

The

platforms feature some very large rocks, some of which must weigh a tonne or

two:

As Yvon led

us into this area, he broke out into oratory in Marquesan, greeting the

ancestors loudly, saluting them and requesting permission to enter this sacred

location. It is standard protocol still practised by visitors to contemporary

maraes as far away as New Zealand.

He

explained in French that the platform we were standing on was reserved for the

chief and his immediate circle of family, elders and advisors, and back in the

day we would definitely not have been allowed up there. From this vantage

point, he used to sit and look down on the tribe at various gatherings:

At the back

of the platform was another reconstructed (although unthatched) paepae:

The modern

posts were inserted into postholes that had been hand-carved centuries ago:

The

platform also had its own firepit:

Here's how

the chief's platform (in the centre) looks from the cheap seats:

Watching

from the cheap seats was this little tiki, who is probably a modern addition to

the site:

Work on

clearing the site and rescuing it from the jungle only began in 1998, and

standing in the middle of it all, you are aware that there is more out there

remaining to be uncovered:

The view

looking back from the jungle end of the arena:

This is the

paepae on the right in the photo above:

On the

drive back over the hill to Taipivai, we caught up with some stragglers from

the group of grazing horses:

Yvon

decided to herd them back over the hill and down to Taipivai with his

Landrover, honking the car horn and shouting in Marquesan at them. As he

explained, it would be getting dark in another hour or two and it was too

dangerous to leave them to their own devices; a passing vehicle might run into

them in the dark. At one point on the downward slope, I got to roll down the

passenger window and shout "bouge-toi!" (shift yourself!) at a horse

that had decided to jump over the roadside concrete barrier in order to escape

from the pursuing Landrover. Much to my amazement he meekly hopped back over

the wall and got back on the road.

Having

herded the horses down to lower land, Yvon then drove us off to Taipivai's

almost brand-new marae (built in 2011 if my memory serves me well). There was

some initial debate about what to do as the main gate was locked, but I settled

the matter by climbing over a fence.

Note the

solar panels, which provide power for the site's lighting.

Reaching

the first paepae, I stopped to ask Yvon about this plastic thatch that I had

already spotted on the other side of the island:

He said

there had been a long debate about it, and some protests from various elders,

but the village had decided that plastic thatch was the way to go: it is more

cost-effective, as it does not have to be replaced every three to four years

like natural thatch does, which also saves a lot of time, as it takes hours and

hours of community effort to redo all the roofing for the marae.

And it

certainly looks the part:

I also

asked him about the wood-burnt finish of various of the posts, which is

something I had not seen in these parts before:

It turned

out that at the end of 2013, a local pyromaniac had tried to burn down the

marae. The community had rallied around and rebuilt it within a few months, but

the legacy of that was that various of the carvings were still smoke-stained. I

was about to explain about how Californians actually do that to their tikis on

purpose but thought perhaps the irony might not be appreciated by this fireman,

who was clearly still pained at all the damage that had been caused.

The effect

was not necessarily bad, and certainly made the tiki posts that had been burnt

easier to photograph:

This one

seems to be saying "what the #$#?"

Soon I was

doing the same, upon spotting this terracotta guy, who was a gift from another

island in the Marquesas:

"Mais

ce petit bonhomme est orange!" (But this little guy's orange!) Yvon

thought my response was hilarious: "That's what various elders said when

they unpacked him - but he's a nice-looking tiki, non?"

There were

some resolutely modern and very striking tiki carvings on the Taipivae marae.

This one looked like something Edvard Munch would have done:

A primitive

pop art effort gifted by the island of Hiva Oa:

It was

still showing scorch-marks from the arson attempt:

I also

asked about the configuration of the marae, wondering if there was any special

significance in the layout:

And was

told that it was designed merely to be practical: covered stands on three sides

for the audience, while the stones at various points are merely there for

performers to sit on while they are waiting to get up to perform.

Down the

far end, there is an open-air platform:

The walls

of which are made from concrete:

Some of the

tikis were also concrete castings:

Polished

concrete with inlaid pebbles in the case of this tiki:

At this

point, reminding me about a disapproving comment I had made earlier that

afternoon about missionaries chopping dicks off tikis, my guide gleefully

called me over to take a special photo of him:

It was a

great conclusion to a wonderful day out and about on Nuku Hiva and I hope I can

return to the Marquesas in the not-too-distant future.

© W.S. McCallum 14 October 2014 - 24 April 2015

Web site © Wayne Stuart McCallum 2003-2017