Music Writing 1986-2003

by W.S. McCallum

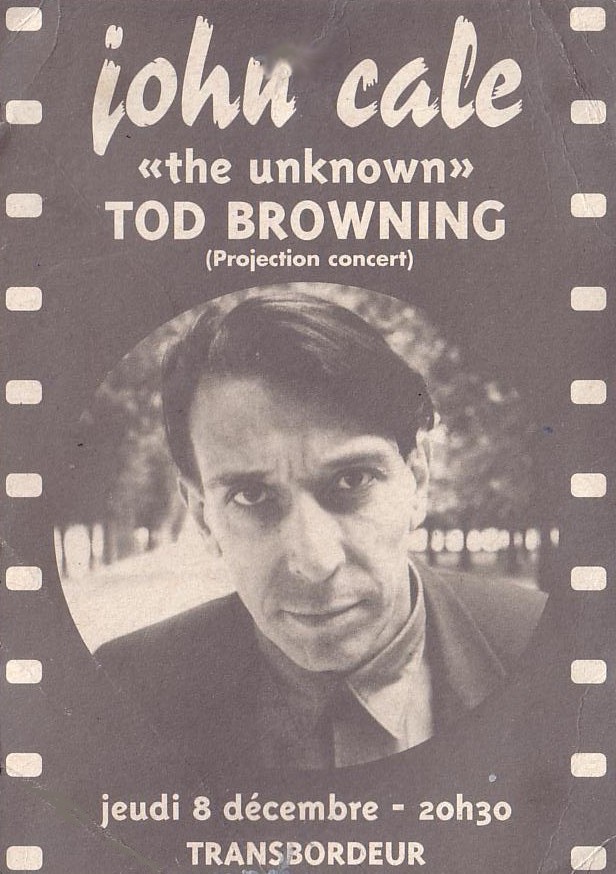

John Cale and Tod Browning’s The Unknown

Le Transbordeur, Lyons

8 December 1994

From 1994 to 1995, the city of Lyons marked the centenary of the invention of modern cinema by two of its most famous sons, the brothers Lumière, with a series of major events. To show that the city had come a long way since Lyonnais and Lyonnaises ran screaming from the Lumière brothers’ converted barn at the sight of a film of a locomotive chugging towards them, a series of sophisticated cinematographic celebrations were scheduled, many of which were focused on screenings of classic films. One of the highlights was John Cale playing his original score to the soundtrack of The Unknown, a silent film from 1927, directed by Tod Browning.

Along with his 1931 film Dracula, Tod Browning is best known for his film Freaks, a human circus that gave the Ramones one of their most famous catchphrases (“gabba gabba we accept you! etc.”). Like Freaks, where a sideshow sets the scene, The Unknown is set in an itinerant setting - a circus - and also, like Freaks, it proved to be a very strange film indeed.

Living just five minutes’ walk from the FNAC ticket office in Part-Dieu, I bought my ticket as soon as the event was announced, and consequently got an excellent seat, right in the middle, about ten rows from the front. Judging from the jet-set finery of some of the assembled local cultural cognoscenti and nabobs seated in my vicinity, I had managed to do well to get a seat so far forward without resorting to le piston (pulling strings - not that I had any to pull).

The venue was somewhat at odds with the whiff of moneyed culture I could smell wafting before the performance. The Transbordeur is best described as a large tin shed, and is one of the main venues for big touring rock acts that play in Lyons. It sits on a bank of the River Rhône, tucked in-between the city park and the main trunk railway line leading to Paris and Marseilles, in a fairly-central-but-not-that-central part of town that took me a good 40 minutes’ walk in the dark winter chill to get to.

The composition John Cale played was originally commissioned earlier in 1994 for a screening at the Posdenone Silent Film Festival in Italy, and a few nights before the performance in Lyons, Cale had played it in Paris too. At about 9pm, he strode out onto the stage at the Transbordeur, dressed in a dark suit, looking every bit the classical piano player as he took his place in front of his Japanese electronic piano. As he sat poised and ready to go, the lights went down, and the film began.

The Unknown is the tale of Alonzo The Armless (played by Lon Chaney), a knife-thrower who performs his circus act by very accurately throwing knives with his feet. He has his heart set on winning the love of Nanon Zanzi (Joan Crawford), another member of the circus troupe. There is a big psychological dimension to the film, and Sigmund Freud might have enjoyed it immensely for that reason alone. Nanon, who has been pawed too many times by a series of lustful men, loathes the touch of masculine hands, which is why Alonzo the Armless sees himself as fated to become her perfect lover. But not if the dastardly Malabar The Mighty (Norman Kerry), who wants to have his wicked way with Nanon, has anything to do with it. After all, what good is an armless knife-thrower in a knock-down fight with a fully-functional strongman? Unless, of course, Alonzo The Armless is not all he appears to be…

One of John Cale’s Paris audience claimed that his performance was little more than ad-libbing and banging on the piano, but I could hear no evidence of that. The playing was tightly structured to follow the mood and flow of the film, and was the perfect, manic counterpoint to a profoundly strange film. John Cale had obviously put a lot of work into the piece, and had come up with something that served very aptly as its soundtrack. It was not your typical John Cale concert - no singing, no “Close Watch”, no “Heartbreak Hotel”… Instead, what you got was just slightly over an hour (63 minutes) of piano playing that went from slow to frantic, but maintained a sense of the dramatic throughout, and served as a foretaste to the far scarier work he was to produce some years later in his soundtrack for American Psycho. It was short but sweet, and I trudged back to Part-Dieu in the cold and the dark very happy that I made the effort to see this unconventional performance.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 18 May 2006

Remember The New Romantics? Music in the 1980s

Rock 'n' roll hit its fourth decade in the 1980s. The musical bastard child of the fifties reached the threshold of its middle years, a prematurely tired and bloated thirty-something, on the verge of a mid-life identity crisis. Rock had grown and grown, to the point where its hulking carcass transcended simple definitions and attempts to delineate it from the pool of cultural influences it wallowed in. Rock is now like jazz in its defiance of any simple labelling. What is rock? Shambling heavy metal morons who all look like they have the same hairdresser? Whitey B-boys sampling twenty-year-old James Brown riffs? Industrial noise? Tired Western musos looting Africa's musical heritage for new ideas? Or African musos looting tired Western musos of their ideas? Squeaky clean teenage bimbos squealing covers of sixties pop hits? Or mumbling Goths? Rock never was easily definable, even in the fifties, when the difference between rhythm and blues and rock 'n' roll was far from clear-cut. Thirty-five years later, rock has become a mix and match of styles, some bizarrely real, others the figments of music journalists' imaginations. NME is just one paper that can take a bow for adding to the confusion. Acid House is believable, but what is Acid Jazz? Hip hop - okay, but hip house? And what is grebo music? For that matter, some are still wondering what “power pop” is (copyright NME 1978). And what's next - hardcore pop, speed reggae, acid House folk? Coming soon to a store near you, the new sounds of the 1990s...

Old Blighty

But that's the future and this is the past. 1980. The year when English music had it all: snob value coupled with mass appeal, a truly British cachet emulated the world over. Punk rock, a well and truly flogged and dead equine corpse in Britain, still had some life in it on distant shores. LA brats found punk was a neat way to hack off their ex-hippy, coke-snorting, “Liberal” parents. Get a crew-cut, swear a lot and wear Nazi paraphernalia. Simple! Here in quaint old New Zealand, always a year or two behind the times, punk culture lingered on into the mid-eighties. Boys High and Christ’s College lads affected Cockney accents, wore anarchy symbols on their schoolbags and made “no government” comments down at the Caledonian Hall or at the Gladstone, without even having heard of Malatesta, Kropotkin or Bakunin. Others twigged on to Two-Tone, ska, and the second wave of British mod. Amongst the first of the eighties revivals, ska in the early eighties usually meant the Specials and not original performers like Desmond Dekker and the Aces, just as mod meant the Jam and not the Small Faces or the Action. For those with more obscurantist tendencies there was the new Liverpool Sound of the Crucial Three and their offshoots, out of which Julian Cope is still a pretentious blot on the horizon.

British is best was the message inflicted by the trendy music media in the early eighties. And England's finest moment of sartorial glory was the flowering of the New Romantics. Hey presto! Hairdressers everywhere oohed and aahed. Punk and all that other stuff had been too nasty, but this - so refined, so chic! Now everyone could be Bryan Ferry (the New Romantic Godfather), or at least Steve Strange. Out went the bell-bottomed trousers and the old Steely Dan tapes. And off went the long hair, to be replaced by some new stylised cut with lots of Brylcreem and some trendy threads. They dreamed of the day when they too, could strike dramatic poses in period costume in the background of the latest Visage, Ultravox or Spandau Ballet video. New Romanticism was the triumph of style over content; the only enduring lesson it endowed to the rest of the eighties upon its passing. Just like punk had never happened, as many were quick to point out.

It was around the time of the New Romantics that the synthesiser kicked the electric guitar off centrestage, and many a novice musician found out that stabbing the electronic keyboard of one of those new portable, programmable synthesisers with one finger, was easier than strumming an A chord on guitar. The British discovered it first and a deluge of synthy pop sounds ensued. 1982 was their peak year - Depeche Mode (named after a Parisian fashion hedbo - très chic), Duran Duran, Soft Cell, Yazoo, BEF, Haircut 100 (the ultimate hairdressers' band?), and the daddy of them all, the Human League. Wet wallies to many disaffected post-punks, the latest in style for others. The triumph of the synthesiser wasn't total, particularly outside Britain. The new American names of the early eighties were still firmly based on a guitar sound - REM, the Long Ryders, the Replacements. Husker Du and a legion of others.

Video Killed the Radio Star

Or so the Buggies thought. They were wrong. Many an old act on the rock scene used the video clip boom to rejuvenate their careers. For art school dropouts, video replaced album cover design as a hot new career field. Who wants to be another Roger Dean when you can direct three-minute forty-second cinemagraphic masterpieces? Rock always contained a certain amount of Hollywood theatricals, but by the eighties they were even more pronounced: Duran Duran with their cover girls in “Girls On Film”, Ultravox with “Vienna” and its old Romantic ambience, and ABC with their music hall “Look of Love”. With the arrival of MTV in the USA, rock video came of age. Non-stop Music TV and its audience of millions allowed record companies to splash out more cash on their groups' videos. Soon video budgets started outstripping those of minor full-length films. Good videos sold records and helped Michael Jackson and ZZ Top hit the peak of their already long careers. Even old fossils like the Rolling Stones got in on the act, hiring Julian Temple to direct a big budget South American epic for “Under Cover of the Night” in 1983. The BBC, predictably, banned it.

Rock video encouraged the message that what now mattered to new artists most was image. Both Madonna and Boy George built careers on image and very little else. Others had image but didn't know how to use it, or sucked themselves into concentrating more on image than music. Frankie Goes To Hollywood are a good example - two great videos and lots of PR hype shifted a very mediocre double LP in large quantities before the media machine ran out of ideas and Johnny Public began looking for something new. The band whose ads hailed them as being "Bigger Than The Beatles" lasted less than 18 months as an international chart act. "Bigger Than The Beatles" - they said that about the Knack back in '78 too, didn't they? I wonder what they're doing now?

The Medium Is The Message

Marshall McLuhan thought so anyway. In the 1980s, more than ever before, the rock medium was TV, and the message involved a mix of do-goodery and undiluted capitalism. The New Generation gulped down their Pepsi sugar water to the sight and sounds of Tina Turner and David Bowie, as unlikely a pair of candidates of anything new as can be imagined considering they were both well into middle-age. Beer companies, amongst others, began sponsoring nationwide tours, both here and overseas. Coors Beer was emblazoned alongside Tom Petty's name, Rheineck alongside that of the Party Boys. Corporate sponsors also gladly jumped on the bandwagon of the biggest show of rock altruism of the decade in 1985 - Live Aid. Behind the smiles of the singers of “We Are The World”, there was a lot of emotion and a substantial amount of calculated careerism. The live global satellite transmission to all those millions of people got more than one band out of the doledrums. Bob Geldof's Boomtown Rats hadn't been a chart act since the late seventies. While croaking Bob Dylan and Joan Baez made fools of themselves in front of their new “Woodstock generation”, record company advertising executives gleefully watched all the free advertising plugs they had squeezed in for their acts under the guise of benevolent sponsorship. And it was all beamed to the largest TV audience in history. Still, some money got to all those starving Ethiopians, didn't it?

Retro-chic

Or "old is new". The 1980s was the post-modernist decade and all too frequently in music, for want of anything new, a lot of people decided to recycle the past. The sixties, for example - the decade the bastards won't let us forget. The Big Chill generation aired their hang-ups on cinema screens and on TV programmes like Thirty Something. ("Oh, God Michael, we're just like our parents!"). A decade too late, the Americans got around to admitting they lost Vietnam, but consoled themselves by squeezing lots of films and accompanying soundtracks of old sixties hits out of it. Those ageing hippies still on the music scene had long ago lost any shreds of their former revolutionary street credibility. The Jefferson Airplane had gone from being children of the revolution and had progressed into being prime candidates for boring old fartdom. Under the name Starship, they managed to send a couple of very stodgy MOR songs into the charts. Pink Floyd rumbled on, with or without Roger Waters. Both the Who and the Rolling Stones broke up, only to reunite once again in 1989. And let’s not mention Crosby Stills and Nash.

And that other lot found themselves getting older too. Before they knew it, 1986 was upon them and they all exclaimed "Well I'll be ****ed - it's been ten years since I first dyed my hair green!" NME performed a “Summer of Love” retrospective, punk-style, complete with a mail order greatest hits cassette. Alex Cox directed a film on Sid and Nancy, a mixture of true love and needlemarks, and those old codgers Sham 69 even reformed. But really, by 1986, the punk generation looked like just as big a bunch of sellouts as Grace Slick and her star child friends. Sneering Billy Idol of Generation X had become the darling of the plastic people, a chatshow guest, Sixteen centrefold and an icon to millions of US teenyboppers. Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols had become the posing guitar hero that punk rockers used to despise so much, and Captain Sensible along with the Damned did some crass covers. Some events were just sad, like Feargal Sharkey's migration to LA and attempted Sinatradom, or the Clash's slow downfall.

To top things off, there was even an attempted seventies revival in 1988 (the disco and flares seventies that is. And then someone remembered just how ghastly that decade really was.

Many performers from the seventies did go on to greater things. In 1984, Bruce Springsteen finally attained the megastardom his PR people had been predicting since 1975. XTC and Madness wrote some of the best British pop music of the decade. Iggy Pop finally got his career back on the tracks, and Wire managed to reform in 1986 without wallowing in their punk past. In the political credibility stakes, Jello Biafra took on the Washington wives in an obscenity charge lodged over an obscene Dead Kennedys album insert, and Frank Zappa stood up in front of a Congressional hearing to tell various Congressmen and members of the Parents' Music Resource Centre that censorship of rock music was a denial of freedom of expression. This was thirty years after the sight of Elvis shaking his hips first shocked America's elders.

But really, the cause of all the nostalgia was the dearth of any true originality in white pop in the US and UK. Britain's indy scene has been on a downhill slide for most of the decade. All the US could come up with in the late eighties was another raft of singer-songwriters and the usual guitar bands of one sort or another. The pop mainstream is too horrendous to bear mentioning in depth. The charts were littered with manufactured one-hit wonders like Times Two doing remakes of twenty-year-old songs. Or worse, the original hits themselves were wandering back into the charts. In 1986, Sam Cooke's “Wonderful World” reached number two in Britain, a quarter of a century after it initially charted. Not many people under thirty-five had even heard of Jackie Wilson prior to “Reet Petit's” chart success in 1986-7, some thirty years after it was recorded.

Rap and All That

Rock's saving grace in the eighties was rap, the newest in a long line of innovations in black R 'n' B since the fifties. By 1988, rap had been around for a decade. Although back in 1978 few people outside New York knew what it was, by the late eighties it was known globally. Rap first broke into the international charts in the early eighties, with groups like Grandmaster Flash And The Furious Five and Whodini. Its big breakthrough came in 1986 when Run DMC's remake of the Aerosmith song “Walk This Way” made them an international success. Suddenly, rap was It. Everything from the obese joviality of the Fat Boys through to the black separatism of Public Enemy became hot product. Twenty-five years after soul, white boys started emulating black Americans yet again, dressing in tracksuit gear, baseball caps and lots of gold chain. VW owners found, to their dismay, that b-boys favoured their hood ornaments as fashion accessories. In 1987, the hot topic of debate was "is sampling ethically sound?", a question of as monumental import as "can white boys sing the blues?" was in the sixties. The answer to both questions turned out to be, "Who cares? They'll do it anyway". The Beastie Boys were amongst the first to end up in court for musical plagiarism, but it didn't seem to stop anyone.

An even newer development in black American music was Chicago House which emerged in the mid-eighties. J.M. Silk's “Jack Your Body” and others mixed up seventies Eurodisco with black soul. The soul old guard hated it, labelling it as too mechanical. It flourished nonetheless. Now House music even has its own offshoots like Acid House, minimalist dance music for acid freaks.

Reggae and World Music

Reggae continued to thrive in the eighties despite the death of its king, Bob Marley, from cancer in May 1981. In his wake, his son Ziggy Marley has done surprisingly well. Reggae, like rap, has had its share of violent deaths. Peter Tosh was the second Wailer to die, murdered in 1987. Amongst other victims of Kingston's gangland violence was the legendary producer King Tubby, killed during Jamaica's last election. But reggae had its triumphs too. Sly and Robbie became reggae's roving ambassadors, working on an incredible number of session projects, helping Black Uhuru into the charts, and scoring success with their own LPs like Rhythm Killers. A number of acts obtained crossover success and sold records to the white listening public in Britain and, less frequently, the USA. Eddie Grant came up with a sound that was as much rock as it was reggae, John Holt became the Frank Sinatra of reggae with his repertoire of standards done to a reggae beat, and Maxi Priest appealed with a gentle commercial reggae, as did the Musical Youth with their cover “Pass The Dutchie”. Most reggae acts remained out of the mainstream though, sustained by their traditional Jamaican audience. Perhaps the most interesting development was the arrival of Africa's first reggae superstar, Alpha Blondy, proof that reggae's appeal is spreading. Its spread is less spectacular than rap, but its gains seem more permanent and it will probably be around well into the next century.

So much else was happening outside the Anglo-American rock axis that the musical press belatedly began paying attention and decided to label it “World Music” around 1986. Both Malcolm McLaren and Paul Simon packed their bags for South Africa in search of new ideas. Simon managed to get a hit album and a blacklisting as a result. The good side was Ladysmith Black Mambazo's international recognition after three decades of obscurity. Nigeria's superstar Fela Kuti had his career disrupted by a prison sentence. Long-established musicians like Franco, Youssou N'dour and Salif Keita broke into the Anglo-American scene via France. Zimbabwe's Bhundu Boys first toured Britain in 1987, musical ambassadors for one of the world's youngest nations. African music is also having its influence on the Caribbean. West Indies groups like Kassav and performers like Franky Vincent, have mixed up disco and African soukous in a style called zouk that is also proving popular in France. Influences like this will give rock an even broader variety in the 1990s than it currently has.

And what's the next fad? Malcolm McLaren strikes again. Look out for vogueing, the new posers' trend which should hit New Zealand by 1990 at least.

Originally published in CANTA No. 24, 18 September 1989 pp. 12-13.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

The Clean, Chris Knox, & The Strange Loves

at the Playroom, Christchurch, May 1989

Craig McNab

Although not unprecedented (the Bats come to mind), the image of Flying Nun acts performing live in the Playroom out in the suburb of Aranui is a bit like the proverbial fish out of water. Complete with its neon ZMFM and C93 signs shining down from the wall, the Playroom is the sort of place I normally associate with wanky cock rock support bands and covers groups. That particular Tuesday night was a bit different. The "sink more piss" V8 boys and their sheilas were nowhere in sight - the alternative crowd was having a night out instead. The queue at the door started forming around 7 pm. By quarter past seven there were around 30 or 40 people, and by a quarter to eight there was a queue of at least a hundred people straggling off into the carpark. Even after someone finally unlocked the doors and everyone streamed inside, over a hundred were left waiting outside as the doormen barricaded them out. People inside who wanted to leave during the concert were told they wouldn't be able to get back in, even if they had paid. And early departures were used to make room for those still queued up outside the doors.

The Strange Loves kicked things off with a very short set that lasted little more than a quarter of an hour. The audience reaction was pretty indifferent, someone even yelled to tell them to sing something they know about in reaction to their songs of forsaken love. Through no fault of their own, The Strange Loves got a pretty raw deal; both from their audience and their publicity people - they weren't even advertised on concert posters and radio ads, and you got the feeling a lot of the audience weren't particularly interested.

Chris Knox regaled the audience with his usual "I'm an obnoxious little bastard, don't you love me?" routine, and played the same set he performed in the Upper Common Room in the University of Canterbury Students’ Association during Orientation, throwing in the odd bum note and wobbly riff. Even with the rough bits around the edges, he gave a good performance, thankfully steering clear of John Lennon covers. He also livened things up with a little wit and repartee on the subject of The Clean, about how he knew everyone was only there to see the Kilgours and ''that little guy with the big nose whose name you can never remember". He closed his solo set with a specially composed little ditty called “We're All Here To See The Clean”, and managed to slag off everyone in the room in the process.

Then there were a couple of Tall Dwarf's numbers. and the ''Tall Clean Dwarfs" getting together to perform “Nothing's Going To Happen”. The Clean themselves were excellent, and after a couple of songs were obviously really getting into enjoying themselves. Although a lot of people in the audience were obviously craving for a trip down memory lane, The Clean mixed in a lot of high-grade new material and avoided playing more obvious older tracks like “Beatnik”. They had also revised some of their older songs: “End Of My Dreams”, that listless coda tacked onto “Beatnik” (a song that has tripped up an endless number of studio radio DJs over the years), got a total revamp and even sounded groovy. The Clean have said that this tour is only a one-off venture and that they have other musical commitments, but I'm probably not the only one who hopes they get around to recording their new songs.

At the end everyone was screaming for an encore and went home contented after a good night out, with the possible exception of the usual no-hopers who managed to get themselves pissed and tossed out the doors. One drunk was still hassling the guy on the door after the concert had ended, shifting from persecuted victim to macho tough guy as the bouncer repeatedly got hot under the collar and calmed himself down in the face of an extremely tempting punching bag.

Originally published in CANTA No. 10, 24 May 1989 p.18.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

The End of UFM

The Beginning of 98 RDU

1989-1990

The 1989 closure of Radio UFM in Christchurch led to a lot of speculation and a certain amount of misreporting. Wayne McCallum takes a look at the last days of one student radio station and the beginning of another.

On Thursday 14 September 1989, the UCSA Executive passed a motion to close down Radio UFM on 1 October. This date was over a month earlier than the original planned closedown in early December. The overriding reason given for the early closure was that UFM had got itself into serious financial difficulties. The 1989 UFM budget had targeted a $10,000 surplus as its goal, but by September the station's financial projections were pointing to a $40,000 deficit if UFM continued broadcasting until December. Sam Cooke, UFM's Station Manager, found himself in an unenviable position: UFM had already reached around a $20,000 deficit by mid-October, and things could only get worse, Station personnel were witness to at least one angry tirade that Sam Cooke experienced from Baz Star, then UCSA's Vice-President. Sam was under a lot of pressure to do something as soon as possible. For him and most of the Executive, early closure was the only option. When the announcement was openly made known to UFM staff and the general public, it came as quite a shock. Except for a select few, little was known of the increasing financial difficulties UFM had been experiencing for some months prior to the announcement of the 1 October closure.

1989 started out looking like a good year for UFM. 1988 had ended acrimoniously when that year's Station Manager, Ruth Morrish, was dismissed by Sam Fisher, then the UCSA's President. That year, Ruth had presided over UFM's largest ever deficit - $39,161. Her dismissal came just before her period of employment was due to end anyway, but occurred as a result of her blowing a couple of thousand dollars’ worth of unbudgeted money for UFM's end-of-year social. With her gone, Executive members looked forward with some relief to Sam Cooke’s takeover as Station Manager for 1989. It was widely believed that Sam had a more professional approach to management than his predecessor. He had the right qualifications, being the first UFM Station Manager to have received radio training at the Christchurch Polytech broadcasting course. He also had a background in studio production, a knowledge of things electrical, and a positive, outgoing attitude. His talk prior to UFM's 1989 broadcast centred around increasing the level of professionalism at UFM, and the station's accessibility to listeners. Certain die-hard members of UFM's old guard loathed him with a passion for it. They muttered about him "selling out" the station and yearned for the "good old days" of Radio U, although not having experienced them directly, they probably pictured them in an overly rosy light. Whatever the case, feeling marginalised within the station, some of this group left. Some were thrown out. Generally, UFM's 1989 on-air sound was a marked improvement over that of 1988. The shambolic announcers disappeared. Playlist songs were no longer left on air for six months because the Programme Director had forgotten they were there. On air, the Station was running quite smoothly.

Off air though, things were not progressing quite so well. Garrett Murnane, UFM's Advertising Manager, complained of the station's lack of a public profile. He couldn't "sell" the station to potential advertising clients. Clients were no longer convinced that UFM was reaching the student audience. Nor were Murnane or Sam Cooke. A 1988 listeners' survey conducted for UFM by Market Probe claimed that only 23% of the student audience regularly listened to UFM. Besides these students, UFM also had a sizeable non-student audience, but these listeners were hard to define: they ranged from the unemployed to yuppies: people whose only common denominator was an interest in music other than the stale fare offered by Top Forty and "Gold" commercial radio formats. This audience left Cooke and Murnane with the problem of running a "student" radio station which wasn't appealing to an overwhelming majority of students, but did appeal to a mixed bag of non-student listeners.

The situation brought to the fore a very old debate in student radio circles. Traditionally, Radio U was designed as an alternative radio station appealing to student listeners. Musically, it offered fare you wouldn't hear anywhere else on Christchurch radio - "alternative music" For some people, "alternative music" conjures up images of depressed boys in black playing punky music, but even in the late seventies and early eighties, Radio U was more than just that. The bounds of commercial radio in those days were so limited that almost anything could be "alternative music". Radio U's format in the early eighties included extremely commercial bands who were only considered "alternative" in Christchurch because local commercial radio programmers were still living in some time-warped version of the seventies where Steely Dan, the Eagles and Rod Stewart would forever reign supreme. Radio U listeners in the early eighties were just as likely to hear top twenty British pop acts like Soft Cell, Visage, Spandau Ballet. Adam & the Ants or the Human League as they were to hear more politically sound punky numbers from the Clash. Since then, the station has diversified considerably, particularly in the area of black music. In 1986, UFM created a number of new specialist music shows, including jazz, blues, soul, reggae and even classical music. Commercial radio being what it is, even today "alternative music'' is nothing more than the 98%+ of recorded popular music that isn't selected for the Top Forty or "Gold" formats at other Christchurch music stations. That's a lot of music.

So much for the "alternative" format; what of UFM's student listenership? In 1986, the newly-established UFM could broadcast its alternative format, happy in the knowledge that in 1985, a Business Administration listener survey for Radio U indicated that 52% of students listened. The novelty of UFM having beaten 3ZM and the newly-founded C93 as the first full-time FM station to go to air in Christchurch didn't hurt confidence either. UFM could be sure of picking up plenty of curious listeners who wanted to hear what FM radio sounded like. UFM could stick to its alternative format, and still represent itself as a student station.

For Sam Cooke in 1989, no such certainty existed. UFM's failure to attract advertising clients was, for him, indicative of the station's failure at being a student radio station. With a 1989 operating budget of over $100,000; a five-fold increase over Radio U's 1985 budget, UFM couldn't afford to lose its student image. Without the financial support from advertising clients wanting to reach student listeners, the station stood to lose a lot of money. As early as August 1989, UFM was running at a projected loss of $33,370. The amount of advertising on air kept declining and this figure had to be revised by September to a $40,000 deficit. For Sam, it spelt the financial and spiritual bankruptcy of student radio in Christchurch.

Sam Cooke's solution was to close up shop and start afresh in 1990. At the 14 September 1989 Executive meeting, speaking on the motion to close down UFM, he stated: "Student radio, as it stands, really died five years ago [given the high student listenership indicated in the 1985 BSAD survey it actually died more recently than that, but let us continue]. It's time to pack up and look for a different direction".

Sam Cooke's planned fresh start for 1990 involved him as Station Manager, leading UFM off in a totally new direction with a mainstream musical format. Sam was out to catch student ZM listeners by offering them the same sort of format on UFM: "Next year we could aim at students, with promotions on campus. We could play the Blues Brothers, The Big Chill, Tour of Duty". As Sam saw it "students don't listen (to UFM) because they don't like the music. There have been four years of amateur management and mistaken student radio philosophies".

Interestingly, when Sam made that last statement, UFM had been broadcasting less than four years. Presumably he included his own period as Station Manager under the category of "amateur management and mistaken student radio philosophies". If so, it's a surprisingly frank admission.

In making such statements to the UCSA Executive, Sam Cooke represented himself as speaking on behalf of UFM personnel. At the 14 September Executive meeting, he requested that it be noted in the minutes that he had the concurrence of UFM staff on the subject of a 1 October closure. Earlier on that night, Chris Whelan, the UCSA Services Officer, was more specific: "Sam informed some [author’s italics] UFM staff about the budget blow-out, and the possibility of closing down. They accepted that, and it was actually the preferred option". "Some" is the key word here. Outside of a handful of people in UFM's paid management, few UFM staff were informed of UFM's financial problems prior to the public announcement following the 14 September meeting. Only a select few were called upon to give their views and Sam Cooke kept things very much quiet until he had managed to pass the early closure through the Executive. There was no station meeting to discuss the situation with all of UFM's staff, for the reason that any such meeting would have created further problems in the form of station staff opposing the early closure.

Sam Cooke's fears were well-founded. Once the issue began coming out in the open, it split even UFM's management. The prospect of UFM going commercial with Sam Cooke leading the way caused a lot of station staff to see red. A petition was started to have UFM continue broadcasting, but with no paid management, so as to avoid the heavy staff costs involved in running UFM. It was argued that an early closure for UFM was simply nailing the lid on the coffin on student alternative radio, something Sam Cooke had an expressed interest in doing. Sam Cooke's generalisations to The Press (29/9/89) only aggravated things. Speaking of "factionalism" within UFM's staff, he said: "There are the people who just want to play really alternative stuff and no mainstream and want to leave all the commercial stuff to commercial radio. Then there is another group which says "Let's play what students want to hear"." Some asked how Sam Cooke could be so certain that the Tour of Duty, Big Chill and Blues Brothers soundtracks were really what students wanted to hear. Or were they just what Sam Cooke wanted them to hear?

Others seriously wondered about his capability to run a "new" UFM in 1990, given what had happened under his management in 1989. How successful would he be at promoting the station to students in 1990 considering his lack of consistent support for UFM's promotions in 1989? His plan to go mainstream with UFM in 1990 was greeted with some dismay. It would lose what audience UFM had and it was dubious that student ZM listeners would suddenly change the listening patterns of a lifetime and tune into UFM on the basis of a similar format.

At the 14 September 1989 Executive meeting, a motion was also passed calling on proposals for UFM's 1990 management to be submitted by interested parties. Sam Cooke was surprised when a far longer submission than his own was handed to the Executive by Carl Hooper, UFM's promotions man; Andrew Glennie, UFM's technical expert; and Dave McKee, UFM's Production Manager. Their joint submission was the one accepted as the basis for further research into setting up the station for 1990. Having approved the principle of running UFM as part of the UCSA in 1990, and having appointed this team to research it, it could be foreseen that the three would end up running UFM in 1990. On Tuesday, 19 December, the UFM research team presented their 1990 operational plan to the Executive. Totalling 96 pages and including a survey of student listeners, the team offered a different path for UFM to the one Sam Cooke proposed.

The team's overall aims were:

- to run UFM as a semi-autonomous self-funding operation within the UCSA

- the revival of Radio UFM as a viable market force in the Christchurch radio market

- the revival of students' interest in their own radio station

- the survival of Radio UFM into the 1990s.

By 1991, under the plan, UFM aimed to be self-funded. To do so would involve attaining clear sales targets, giving clear guidelines to all staff as to what was happening at the station, and programming music which would attract a wide range of listeners, as well as student news. The report attributed UFM's failure in 1989 to "the lack of motivation by the wider staff" at UFM, the inability of UFM management to communicate with staff, a problematical accounting system and, indirectly, the UCSA Executive. To overcome these problems in 1990, the report stated UFM would have to rely heavily on promotions to increase the station's visibility. Concerning UFM's public profile, the report's survey results were encouraging: 36% of students surveyed listened regularly to UFM, while 60% stated they listened either frequently or irregularly, while 89% were aware of the station's existence. The report stated that having dispensed with 1989's "combination of the lack of motivation of the promotional team, and the restrictions imposed upon them by the Station Manager", UFM could confidently move forward in its promotions, raise the station's profile, and increase student listenership.

The report added that with a proliferation of FM radio stations aimed at the over-30 age group, UFM had no real obstacle to becoming "the only real youth-orientated radio station in Christchurch". Rather than copy ZM's format, the report commented "there is no reason to become the fifth in a series of Christchurch radio stations which have adopted variations on a similar theme and actively compete against each other. Instead, we believe UFM should keep the basic concept of its programming alive".

Following the report's acceptance by the Executive, Carl Hooper was appointed as Station Manager on 20 December 1989. From then until 19 February 1990, the team had a busy time painstakingly rebuilding the basis for student radio in Christchurch: The major step taken was to change UFM's name. Given the bad press UFM had received, a new name was deemed appropriate, hence 98-RDU. 98-RDU's News Editor, Greg Ryan, commented "we really have to do something definite to disassociate ourselves from last year".

Along with the new name has come a revitalised approach to promoting the station's image. Colin Weir is organising 98-RDU's promotions this year and he stated that the station would be highly visible around campus. Over Orientation, 98-RDU will be running a car rally, a "Great Lilo Extravaganza", theme discos and a stand where merchandise and the new station subscriber cards can be bought. With a subscriber card, RDU listeners will be eligible for cut-price merchandise, discounted tickets to concerts and discos, radio competitions and the station newsletter. Colin Weir pointed out that "besides that, subscribers will have the knowledge they're helping to keep 98-RDU on air".

98-RDU's news department is also a new growth area. Along with regular news spots during the day, Greg Ryan will be aiming to provide headlines between news slots. Providing news has always been a particularly demanding job for student radio as it requires a dedicated team of people for the detailed preparation needed of regular daily news spots.

Finally, and most importantly, has been the new station management's changed attitude to its part-time staff. Dave McKee, RDU's Programme Director, has been intensively training staff to avoid the on-air accidents student radio is renowned for. The day before broadcast, the entire staff was invited to meet, to hear and talk about the station's history and direction. There is now the realisation that a small group can't run everything at RDU and communication with all staff is the key to a better station. 98-RDU has learnt from UFM's mistakes. UFM may have ended, but RDU is just beginning.

Postscript: RDU survived and prospered in the 1990s. 2006 marks the 30th anniversary of student radio in Christchurch New Zealand, and the 20th anniversary of its FM broadcasts.

Originally published in CANTA No. 1, 26 February 1990 pp. 10-11.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1990.

The UFM Reggae Party

with I and I

Romanov's, Christchurch June 18 1989

Some people were a bit doubtful when they heard that Glen, UFM's Reggae Show host and Tuesday night DJ at Romanov's, was organising a reggae party on a Sunday night. Like UFM's two recent record release parties at Romanov's it turned out to be a big success. People started arriving about 7.30 p.m. and by 10 o'clock the place was full with even more people on the way. Any fears that people might not want to go out on a Sunday evening proved misplaced. When you think about it, what else is there to do on a Sunday in Christchurch? Faced with a choice between CV [TVNZ’s short-lived Sunday night music show] and Romanov's, it's not hard to make a swift decision.

The crowd was a cross-section of people, including UFM listeners, some of Romanov's regulars and some Maoris who might not normally turn up at Romanov’s. Glen provided them with a good mix of music, although they avoided the dance floor unless there was something playing they were familiar with. Glen certainly enjoyed himself, taking the opportunity to throw in some Jamaican DJ toasting, clap his hands and jump around on the dance floor when he wasn't spinning discs.

I and I were the perfect band for the evening, and now have a four piece line-up which is a match for any northern bands like Dread Beat and Aotearoa. Some of their songs cried out for a horn section, although they managed to fill the gap with some good singing. They played two sets, one starting about nine o'clock, the other past ten, which went without any hitches apart from a brief delay caused by a loose connection just at the beginning of their second set. DJ Glen filled in with another record at the band's request: "I suppose you want to hear some reggae?".

By the end of the band's second set, the dance floor was packed with people, who kept it up after I and I had finished as Glen played more records into the morning hours. It was a great night out listening to bright and cheerful music that could become a regular monthly event given support and encouragement. If you're in Romanov’s mention it to the staff. An evening with DJ Ranking Glen and the Rastas is one hell of a lot more enjoyable than sitting in front of the idiot box suffering the lame wit and shaky wisdom of CV's hosts.

The only down side of the evening was getting hassled by two cops when I was going home through Ilam. They obviously had nothing better to do at 1.30 on a Monday morning, but then that’s Christchurch for you.

Originally published in CANTA No. 15, 26 June 1989 p.15.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

Tarnished Gold - Classic Hits Rock Radio in the 1990s

Everyone has morbid fascinations. The sort they don't actually like to admit publicly but nevertheless fail to shake off. Over the past few years one of mine has been trying to chart the mental journey involved in Gold (Classic Hits) radio formats.

The inconsistencies in these radio stations' playlists, which claim to represent the greatest pop and rock of all time, is stunning to behold for anyone with even a vague interest in rock music's past.

Why do they thrash to death songs by musically short-lived performers like Doctor Hook and Mark Williams, while ignoring musical giants (in prestige as well as in terms of sales) like James Brown and B.B. King? How come the only Small Faces songs you will hear on Gold radio are "Itchycoo Park" and "Lazy Sunday"? Why are old Kiwi chestnuts like "She's A Mod"played over and over while other sixties hits by the Pleazers and ignored? Why do they occasionally play Jefferson Airplane, but not Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Grateful Dead, or Moby Grape - fellow San Franciscan bands which all had hit records? And what happened to all the classic reggae, blues and jazz of the last thirty years?

The simplest explanation for any or all of gold radio's musical deficiencies is that traditional commercial radio programming troika of crass commercialism, musical dullness and sheer ignorance. Given the dominance of these three elements over the playlists of classic hits radio stations in New Zealand, it is a wonder that these stations manage to reflect anything at all of rock'n'roll's development since the 1950s

It is interesting to try and gauge the mental processes which lead to artist X gaining acceptance into the classic hits radio pantheon of greats, while classic artist Y's recordings are left to gather dust in the sound archives.

Something that should not be forgotten is the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation tradition. The bulk of senior station personnel working in commercial radio in New Zealand in the early 1990s received their musical socialisation via the NZBC, the monopoly broadcaster in its day. Typically they are baby boomers or post-baby-boomers (not quite Generation X types) who came of age in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. They grew up listening to ZB or ZM stations, with the exception of the small but increasing number of private stations that started coming onto the radio broadcasting scene from the 1970s. To get their modest positions in the radio hierarchy, the bulk of them were obliged to work for a time within the NZBC, accepting the musical narrowness of its pop music station formats as a basic tenet of daily life.

Although there are some exceptions, classic hits stations tend not to play songs which were not featured on the ZB and ZM stations in days gone by. The NZBC didn't really catch up with rock'n'roll in its musical formatting until the early 1960s, and even then in the most begrudging manner. There are tales of now middle-aged DJ's who, in their youth as junior announcers, were only allowed by their RSA generation bosses to select one rock'n'roll record per shift on air. Apart from the big names of the 1950s, like Elvis Presley, Bill Haley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry, you won't hear a lot of good primal 50's rock'n'roll on gold radio, because the NZBC didn't play it in the old days. Consequently, classic hits radio programmers, who received their musical education from the NZBC, show little on air appreciation of 50's rock four decades later.

A good example is Ritchie Valens, from whom not a peep was heard on commercial or state radio in New Zealand until the film La Bamba was screened in 1987. Now his hits, or at least covers of them, do get airplay on classic hits radio, but only because of the film. Then there is the case of James Brown. What radio station would have touched "I Feel Good" before a department chain store in New Zealand featured the song in its TV advertising? Even now, it will be a long time before you hear "King Heroin" on a classic hits station.

Towards the other end of classic radio's chronological boundary is the 1970s, the decade when NZBC programmers lost what tenuous grasp they had of modern musical developments. One of my formative, and frightening, memories, is the summer of 1976 to 1977, when all you could hear on the radio was high rotate playlisting, dominated by Eagles songs. Today classic hits radio shows little or no appreciation of the new styles and music that were taking artists into the top twenty from 1976. Those 80s artists which do feature tend to be old dinosaurs from the 1970s.

In addition to inheriting the old NZBC chronological biases, classic hits radio displays NZBC geographic biases. If it was not recorded in Britain or the United States, you are unlikely to hear it on gold radio. If you were a major Kiwi band outside this select group, and somehow managed to get air play all those years ago, you might as well not have existed. Most of the rhythm and blues on classic radio consists of white covers bands (as they were in their early days) such as the Animals and the Rolling Stones. For similar reasons, gold radio does not play much in the way of reggae outside of Bob Marley, who was too big for even them to ignore. Otherwise they would rather play Debbie Harry (she prefers "Deborah" these days) singing "The Tide Is High" than the Paragons, and Paul Young signing "Love Of The Common People" in preference to Nicky Thomas. Let's not forget funk, which loses out to sanitised white-orientated disco. Forget Parliament, didn't the Bee Gees invent disco?

Then there is the undefinable programming criteria linked to the old catch phrase "not up to broadcast standard", the bugbear of any New Zealand performer wanting to get airplay. This involves some or all of several considerations. Firstly, a song usually has to be under five minutes long. Kraftwerk's "Autobahn", in spite of being an international top ten hit in 1975, won't get a lot of play in full because it is 22 minutes 30 seconds long, which upsets the timing of scheduled ad breaks and promos."Hey Jude" by the Beatles, which clocks in at over seven minutes, usually gets faded out somewhere in the "la las". Nor will classic hits radio play anything raucous unless it went to at least number five in the Billboard charts. You will hear the Troggs doing "Wild Thing"but forget about ever hearing the Sonics doing "Strychnine" or "The Witch".

Lastly, classic hits radio does not like songs with politically contentious lyrics or anything that is overtly to do with sex or drugs. This is why they are not great fans of the Sex Pistols, and perhaps why it has been a while since I heard Lou Reed singing "Walk On The Wild Side" on one of those stations. It's possible they woke up to the references to transvestites and oral sex.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum December 1990

The Christchurch Music Scene: 1990

There are currently mixed feelings regarding how the Christchurch music scene will fare in the 1990s. Pessimists point to certain events over the last couple of years as being indicative of a decline in local music. Amongst others, Flying Nun's shift to Auckland is seen as a bad sign, as was the Gladstone's conversion into the Durham Arms, and the closure of Audio Access Studios. But whether these happenings are truly the bad omens they are made out to be, is open to doubt. Flying Nun Records' shift to Auckland should be seen positively; a sign that Roger Sheppard and company are moving on to bigger and brighter things. It may now be slightly harder for local bands to get recording contracts following their shift, but it should be remembered that even while Flying Nun was based in Christchurch, that was no automatic guarantee they could afford to sign up every band that wandered in off the street. As for the Gladstone's change of image to the Durham Arms, complete with tacky designer interiors and suburban and western music, the pub was displaced as the Christchurch music venue some years back. Awful as the current setup must seem to old patrons from the early 1980s, it's certainly no worse than the Gladstone's previous incarnation as a headbangers' hangout. Besides which, the pub was always an atrociously ugly building anyway. And not everything happening musically in Christchurch of late has been bad. On the positive side, Breathing Cage did win the Rheineck Rock Awards in 1989, the Blues Club opened and there are still new bands springing up.

New bands do admittedly have a hard time starting out in Christchurch. Getting an audience isn't easy, nor is getting recorded, but then it never was easy to make it big here. No Christchurch rock band has had a top ten hit overseas since Ray Columbus & The Invaders and Max Merritt & The Meteors left for Australia in the 1960s. They were very much lucky exceptions to the rule of obscurity even back then. Then, as now, there wasn't much room for originality in local rock music. Today, in dozens of suburban booze barns and in more than one inner city night club, musical mediocrity rules supreme in the form of various covers bands. When people moan about the state of Christchurch music, they have much cause for complaint. For my sanity's sake, if no one else's, this piece won't be concerned with the relative merits of, say, the Palladium's resident band alongside the Xanadu's. Suffice to say, if hair-gelled guitar heroes going through the motions of performing overseas chart hits of the seventies and eighties is your thing, you shan't be stuck for choices in Christchurch.

If you're looking for original, or at least different fare, then here on campus is obviously the place to start. There's Orientation of course (having picked this programme up, I assume you won't need me to tell you all about that). Also happening on campus throughout the year are various steins, and lunchtime concerts in the amphitheatre. In the Upper Common Room both the Curious George Club and the Jazz Club provide regular evening entertainment. For information on all these, be on the lookout for posters around campus, read your CANTA and listen to 98 RDU.

Beyond the confines of campus, the Subway is the name habitually dropped by the trendy. The Subway is at the New Zealander Tavern, 270 St Asaph Street. It's an oddly-shaped and slightly poky bar which plays host to a multitude of bands of one sort or another. Pressed for a concise description of what they're all like, white boy post-punk scarfie music is the phrase which comes to mind (meant in the nicest possible way, of course). Flying Nun bands like Snapper, the Jean-Paul Sartre Experience and Breathing Cage, tend to appear at the Subway. A few other acts which have played there over the last few months include Perfect Garden, Black Spring, the Holy Toledos, the Strange Loves, Don't Make Noise, Into The Void and so forth.

It's also worth mentioning that if your mode of transport is at all valuable, you should park it some distance from the Subway. Across the road lies an establishment called the King George, frequented by various members of local motorcycling fraternities and, periodically, visiting members of the constabulary. Yours truly had his bike flogged from outside the Subway one night, so be warned.

The Subway has more or less taken over the "alternative" end of the Christchurch music scene, but there are other venues where these acts surface from time to time. The Carlton, on the corner of Bealey Ave and Papanui Road, was where both the Straitjacket Fits and Spud played when they passed through Christchurch on their national tours last year. Other acts which played at the Carlton in 1989 included Bailter Space, Into The Void and the Jean-Paul Sartre Experience. Also the Playroom Night Club at MacKenzie's Hotel, 51 Pages Road, books Flying Nun acts now and then. The most notable example last year was the Clean. The Playroom also recently booked the Backdoor Blues Band and Jenny Morris. The Carlton and the Playroom aren't the only places, apart from the Subway, which occasionally book interesting original New Zealand acts. Even the much maligned Durham Arms hosted the Warratahs last year. They're usually irregular events at, best though.

In amongst all the bland covers bands out in publand, there are a few acts worth watching out for. It you're into heavy metal, one place where you could join the lads is at the Blenheim Road Hotel, 280 Blenheim Road. Hammerack is the resident band there, while Strikemaster even passed through a few weeks back. The Blenheim Road Hotel also hosted the Heavy Metal Awards last year, and they look like becoming an annual event. Warner's in the Square, is a regular venue for Irish folk music, some performed by Irish bands. And the immortal Ritchie Venus and the Blue Beetles shouldn't be forgotten. They're the house band at the Fitzgerald Arms on the comer of Fitzgerald Ave and Cashel Street. For good rock'n'roll music you can't go wrong with Ritchie and the boys.

For blues and hard rock, the Valley Inn Tavern on the corner of Marsden Street and Flavell Street is the place to go. Featured there are acts like Blues Power, the Icemen and the Dwellers. On the topic of blues, you needn't really go any further than the

Blues Club, 99 Tuam Street. The venue was set up by a group of blues fanatics who have also organised some great tours by U.S. performers in past year. Musically, it's one of the busiest spots in Christchurch. The Club's recent acts have included Helen Mulholland & the Hound Dogs, Blues Power, John Roulston, Touchwood, the Beagle Boys and Paul Ubana Jones, amongst others. For a good night out, the Blues Club is recommended.

Speaking of clubs, I & I play reggae every second Sunday at Cats, 152 Manchester Street. I & I are also regulars at the Dux de Lux Restaurant at the Arts Centre. The Soho Bar & Grill, 142 Lichfield Street, featured the Prodigies amongst others in 1989, as well as providing different theme discos. What's in store there this year is yet to be seen. The Soho has yet to find a firm niche in Christchurch's entertainment scene. They have a good setup, but haven't really established an identifiable image. A club that has got its image together is Daniel's, 124 Lichfield Street, which has a good reputation for black American dance music. For quieter entertainment, you could try Boomtown Cafe in Hereford Street opposite the Reserve Bank. (The latter offers its own form of late-night entertainment, but not so much of a musical nature.) The Boomtown Cafe offers folk, blues and classic performers. They also have an open mike policy, so if you're keen, you can be part of the evening's entertainment.

Finally, there's outdoor concerts. Christchurch City Council organises Summertimes, which will be just finishing as you read this [in February 1990]. However there are regular lunchtime and Friday evening concerts in the Square throughout the year. Beware of proselytising Christian bands though, who turn up to spread the word with depressing regularity. The Arts Centre has plenty happening outdoors too, both in the form of buskers and lunchtime concerts on Fridays. In addition, the Arts Centre stages mixed-media performers. Dinosaurs & Doves, NZ Made and the Flying Kiwi Circus are three recent examples.

Owing to the fact this article was written a month before publication, it's impossible to give you a rundown of upcoming events. To stay in touch with what's happening, read CANTA, listen to 98 RDU, watch out for all those posters around campus and consult the entertainment pages in the Thursday edition of the Star and the Friday' edition of the Press. You won't know what's on if you don't bother to find out, although hopefully by now you'll know some of the places to look.

Originally published in Orientation Preview Magazine, February 1990 p. 4.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1990.

Garden City Beat: Rock ‘n’ Roll in Christchurch in the 50s & 60s

In researching this article, I had look at some old back copies of CANTA (the local student newspaper) to see if they could furnish me with inside details on what was happening around the Christchurch scene in the sixties. Sadly, it was a wasted effort. It seems rock 'n' roll was considered a bit too low-brow to be of interest to student readers as late as 1968. That was the year a CANTA music reviewer hailed the bossa nova as the happening thing in modern music. A year later, CANTA did start giving coverage to rock, but the acts reviewed were mainly overseas artists.

Ten years before CANTA was belatedly discovering popular music, Christchurch's first rock 'n' roll act, Max Merritt and the Meteors, were already established. Max Merritt, like many others of his generation, had his eyes opened to the new sound of the fifties through Bill Haley and the Comets, and Elvis Presley. The first large dose of American rock ‘n’ roll the youth of Christchurch got was in 1955, when the film Rock Around The Clock screened here. Local newspaper ads for the film hailed rock 'n' roll as the latest American craze, in much the same terms in which people then viewed the hula hoop.

For Max Merritt though, rock 'n' roll changed his life. When he left school in 1956 at the age of 15 to become an apprentice bricklayer, he started up own rock 'n' roll band, the Meteors. They started playing covers of what little American rock 'n' roll was being released in New Zealand back then; mostly white mainstream chart hits.

When the Teenage Club, Christchurch's first youth centre, was set up in Carlisle Street, Addington, at the Railway Hall, Max Merritt and the Meteors must have seemed like a fairly logical band to book for teenage entertainment. The Club ran from 3.00pm till 10.00pm on Sunday afternoons, and such was the band's popularity that they turned it into Christchurch's first (and at that time only) rock 'n' roll venue. Crowds there in the late fifties numbered between 700 and 800.

It wasn't too long before the band was signed to a record label. In 1958, the Meteors had their first hit single “Get A Haircut”, released. The song was all about the perils of attending a fifties kiwi barber's shop, back in the days when a trim meant a crew-cut and cool teens had more sense than to ask for it short. In 1959, the Meteors' music was affected by the opening of the US Air Force’s “Deep Freeze” Antarctic operations at Harewood. U.S. servicemen started dropping by the Teen Club and, wanting to hear a bit more than the slightly dated mainstream fare that Merritt and the lads were playing, started lending him their favourite records, personally imported from the USA. Of even greater use were the imported Fender amps and guitars they got through Deep Freeze contacts.

Nonetheless, the Meteor's 1960 LP, C'mon Let’s Go, retained a fairly safe repertoire for kiwi consumption. The band even did an up-tempo version of “The Tennessee Waltz”. In December 1962, the Meteors had decided to go to the big smoke of Auckland in an attempt to make a name for themselves nationally, like Johnny Devlin did. They arrived in Auckland only to find that another Christchurch act, Ray Columbus and the Invaders, had arrived a fortnight earlier and had stolen their thunder. Like Merritt's band, Ray Columbus had Deep Freeze contacts too, and they had the gear and the repertoire to upstage Auckland's bands. Back in Christchurch, Ray Columbus had been very much overshadowed by Max Merritt's success. Columbus had nonetheless built a firm following through a succession of changing backing line-ups, before he formed the Invaders. He was even given his own four-part TV series, Club Columbus, at the newly-established Christchurch BCNZ studios.

The Invaders' shift to Auckland gave them a considerable boost. Eldred Stabbing of Zodiac Records signed them up for a recording stint and they released their first single, “Money Lover”, in April 1963. It flopped miserably, mainly due to Radio New Zealand's unwillingness to play new rock 'n' roll, and particularly a song written and performed by New Zealanders. It's interesting just how little some things changed subsequently on the New Zealand music scene, with such practices still being common in the NZ radio sector in the 1980s. The second single did alright however. Called “Ku Pow”, the track even got airplay in Sydney, which prompted the Invaders to try out Australia in November 1963.

And the rest is history. After a lot of hustling, the Invaders managed to crack the Australian charts with a song called “She's A Mod”, written by an Englishman. They didn't do quite so well with their following singles, and broke up late in 1965.

Max Merritt and the Meteors had an even harder time than the Invaders. With Columbus having beaten him to Auckland, the city turned out to be only a slightly bigger musical goldfish bowl than Christchurch, this time with Columbus as the big fish. The Meteors did achieve a good reputation in Auckland in the end, and became house band at Viking Records, before they moved permanently to Sydney in December, 1964. In Australia they had a series of line-up overhauls over the next few years, toured a lot, got into soul music, and had a nearly disastrous car crash. For their efforts, Max Merritt and the Meteors didn't get their first international hit, “Slipping Away”, until 1975.

Merritt and Columbus set a pattern for successful Christchurch acts: establish yourself locally, move , then hop over to Australia if you can.

Dinah Lee also followed that trail. She's thought to be New Zealand's most successful female vocalist of the 1960s. Her career started in Christchurch in 1960, where she began singing in her father's nightclub, aged 15. In 1961 she made her TV debut on the Christchurch show, Time Out For Talent. In 1963 she shifted to Auckland and got signed to Viking Records. Backed by Max Merritt and the Meteors, her first single, “Don't You Know Yockomo?”, became a hit in both New Zealand and Australia in 1964. From 1965 onwards, she was based in Sydney, but still returned to Viking's studios in Auckland to record. Probably her best known hit is “Do The Bluebeat”.

By the mid-sixties, the sound of local rock 'n' roll was changing. The beat music of British acts like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds and the Pretty Things, was making its mark in New Zealand. All of the aforementioned bands toured Australasia, and their versions of black rhythm and blues numbers prompted a wave of Christchurch bands to attempt their own versions.

Dave Miller and the Byrds were one such band. They were big names around Christchurch by 1965. Dave Miller had started out in the early sixties, providing backing vocals for one of Ray Columbus's early bands, the Downbeats. With Brian Ringrose, a former member of the Invaders, and Phil Garland, later to become one of New Zealand's best known folk musicians, amongst others, Miller set up a group called the Playboys. They changed their name to the Byrds in 1964, just as the L.A. band of the same name hit the international charts. Neither of the bands had any connection, but the Christchurch lot can't have been too worried, because they kept their name.

The Byrds moved to Auckland in 1966, released some singles with Zodiac Records, then broke up in 1967. Dave Miller moved to Sydney and formed the Dave Miller Set, but they never made it on the Australian scene and came to an end in 1969.

Peter Nelson and the Castaways were another of Christchurch's best beat groups in the mid-sixties. Formed in 1964, they got recognition on the TV show Teen Scene in 1965. Although they looked fairly respectable in their matching suits, they specialised in gritty R'n'B, Animals style.

The Castaways' forays north were to Wellington, rather than Auckland. They first arrived in Wellington in September 1965, and recorded “Down In The Mine”, the first of four singles completed at Wellington's HMV studios. In July 1966, they crossed the Tasman, but Peter Nelson left the group in Australia. By 1968, they were back in Wellington, but their performances were delving increasingly into cabaret.

Perhaps the most deranged of all Christchurch's beat groups was Chants R'n'B. Described by the Australian rock historian, Glenn A. Baker, as one of the roughest garage bands of the 1960s, the Chants formed in 1966 and were residents at the Stage Door, in Hereford Place.

The Stage Door was a two-level venue, with a coffee bar at street level. The basement was where the music happened. One visitor described it as a "hideout for long-hair boys", back when having long hair was enough to get you accused of homosexual tendencies and beaten up by returned servicemen. Of the cellar, he commented, the "place is a maze of concrete pillars, painted black, as are walls and low ceiling. Initials scrawled all over. Very dark. At back of room, when eyes became accustomed to darkness, thought I had stumbled on couple making mad passionate love, but decided only petting ... impossible to sum up Stage Door, but whatever it is, it ain't the YMCA Annual Dance".

In this environment, Chants R'n'B played very loud music. Trevor Courtenay, their drummer, used to liven things up by swinging from the rafters, while their singer, Mike Rudd, would feign death on stage à la James Brown.

Chants R'n'B moved north in June 1966, and spent about a month in Wellington. It was there that they recorded their only two singles, “I've Been Loving You Too Long” and “I'm Your Witchdoctor”, on Action Records. Tim Piper, their lead guitarist, made a minor legend of himself in Wellington, when he succeeded in nailing his guitar to a stage floor in mid-performance. The band later shifted to Melbourne, but fell apart after only a brief initial success there. The various members of the group were active on the Australian music scene into the seventies.

Back in Christchurch, the Blue Nazz, another white R'n'B band in a similar vein to the Chants, took over the Stage Door residency. By 1967 there was an active club circuit in Christchurch, and they had some good competition. The Vacant Lot at The Mecca in Tuam Street were a popular act. At the Plainsman, the Invaders' hangout in the early sixties, the Jagged Edge were the resident group.

It was around the end of 1967 that the first hippy bands started surfacing. While other groups stuck to white soul music and R'n'B, the Anarchy decided to go out and get decidedly weird. Playdate magazine described them thus: "I can't imagine them being too much in demand for church socials and other private functions, but I guess their bare-chested, motif-painted torsos, wide-brimmed felt hats, hippy beads and bare feet, set them apart.”

Things had changed a lot since Max Merritt first tuned in to Bill Haley and Elvis.

Sources

John Dix: Stranded In Paradise

Roger Watkins: When Rock Got Rolling

Playdate magazine

The Christchurch Press

Originally published in CANTA No. 10, 28 May 1990 pp. 10-11.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1990.

Boogie Chillun: The Backdoor Blues Band

Friday night at the Gladstone. Outside it's cold, dark and windy. Inside, the Backdoor Blues Band are just starting their act. The curtains come back and the standing-room-only crowd starts cheering as they launch into Sly & The Family Stone's "I Wanna Take You Higher".

Ted Clarke describes their influences as being the blues-makers of the fifties. People like Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, Screaming Jay Hawkins, B.B. King, as well as soulsters like Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett. He doesn't have much time for blues "purists" and thinks British 60s blues artists were too po-faced.

It shows. Back at the Gladstone, everyone's having a great time. The band are jumping round like rubber hands, as is the audience, when suddenly all the house lights come on. Blinking, people look around to see what the hell's going on. From the back of the room, a uniformed man pushes his way through the crowd. The boys in blue have arrived. The cop comes to a halt amongst the tables on the right hand side of the room and starts questioning someone. Unperturbed, the band plays on, singing the chorus "I think I love you" over and over again.

Ted Clarke leaps off the stage onto the tables and strides across them towards the cop, shouting the chorus into his microphone. The cop pretends not to notice, turns around and pushes his way out.

Ted Clarke:

"Usually, I don't like them coming into a gig like that. I think it's basically rude. As for invading a theatre or something, they wouldn't, do it. But they feel because it's rock ‘n’ roll they can invade a show... and it’s just outrageous… I mean, our lighting crew spent all day setting up a lighting show and the cops bowl in and turn all the house lights on, which effectively destroys any atmosphere created. It's just out of hand. I was very angry on Friday night when they did that - I was provoked enough in jump out on some tables and take the piss out of them, but usually I prefer to do it in a humorous way, and that makes them look silly.

We were just in Invercargill the other day and two cops walked in. I did a handstand half way across the pub, stood about three inches from them, and tipped a woman constable's hat off with my foot."

The show continues. By half time, everyone in the pub is sweating in a sea of cigarette smoke. There's a rush for the bar and the toilets. The second part of the show starts with the band bathed in blue light, giving their black and white-checked clothes a phosphorescent look.

The pub starts bouncing to the music

Sunday evening. It's just getting dark when I arrive at the motel for an interview. After a short explanation of whom I am, I'm ushered into their suite by the band's road manager. Ted Clarke is sprawled on a bed, watching snooker on the TV.

After a misstart we move to an adjacent suite. As we leave, I'm asked how long we'll be. I hazard a guess and say twenty minutes. We sit dawn. Finally, a chance to ask all my burning questions.

W.M.: "So, where do you buy your shirts?"

T.C: "I have an op shop fetish. From town to town, I usually try to hit the op shops wherever I go and I've picked up a few good ones that way. Where do you buy yours?"

W.M.: "I'm not wearing one at the moment."

T.C.: "A lovely skivvy though."

W.M.: "How did the group start?"

T. C.: In Dunedin, at the end of 1982 when we were at varsity.

Three of us; myself, Ainsley Day, and our old guitarist had all gone to school together in Hamilton. We kicked off there and it was very much a fun time sort of thing. Very casual. I'd never played in a band before. Some would say I still can't: It wasn't the most musical of ventures, but it was a lot of fun and it was always quite popular."

W.M.: "Have you got more 'serious' now?"

T.C.: "Oh definitely. It's still a lot of fun; but obviously it's far more professional. We live off it now. We don't live great, but we do survive and I'm quite proud of that achievement. Especially in a country this size. For a band as large as the Backdoor Blues Band it's a virtual impossibility to live off it, but we manage to subsist. We had very humble beginnings, but then it gradually sort of evolved professionally when our new band started off in Wellington and things have really taken off since then."

The progress made hasn't been without problems however. Their record, released last year, was predictably ignored by commercial radio. Ted Clarke later mentions that he's met radio programmers who still haven't heard of them. This is despite the fact that they're currently the biggest live band in the country. When asked if the band has any ambitions to go overseas, he replies in very definite terms, emphasising that they're not going to try Australia because it's a "graveyard for a lot of New Zealand hands".

Zimbabwe is mentioned as a possibility, as they have contacts there.

The interview is coming to a close when Ted Clarke suddenly asks if I'd like a bit of scandal for my article. His bone of contention is the $6 price tag placed on their show at the University of Canterbury Students’ Association Ballroom. It was originally understood that the price would be $8.

T.C.: "We've got to make sure when we do play that we make some money. We have to be businesslike about it because we're going to get over-exposed... you've got to make sure you get some money out of it to last you through those periods when you're not touring..."

W.M.: "Usually the charge is $8."

T.C.: "Yeah, I don't know how they justify it at all... I'll take some action, I'm not sure what. I've only been informed of it an hour and a half ago and I've been absolutely livid.

It's just another nail in the administrative coffin as far as I'm concerned. I don't think it's fair that students at Canterbury University should have to miss out on entertainment in the future because their administration is so inept.”

W.M.: "Canterbury isn't a member of the Student Arts Council any more. Do you think that's the reason?"

T.C.: "I would have thought it would enable them to independently operate on a good level but I think ultimately, they might need someone to answer to.

The comment was made that it was political. If people at that sort of political level, which is hardly earth-shattering stuff, if they can't operate for the interests of the people who've elected them, what hope is there for anyone?

I've had phrases tossed around me by student politicians in the near past, like things being 'politically unsound'. These are the sort of phrases that your 1986 yuppie-to-be student politician is fond of spouting. It makes me sick quite frankly. It further rams home the fact that university is just becoming a meeting ground for all the middle class... Our dealings have been bloody hopeless. To be met with this sort of response. We're doing a gig tonight for about $2,000, which might sound like a lot of money..."

W.M.: "But most of it goes on equipment costs."

T.C.: "Yeah, and it's the big gigs. Because we're playing 700 people there, there aren't 700 people who are going to come and see us at the pub. We did very well at the Gladstone this weekend, but not as well as we would have if we hadn't been doing Canterbury University on Sunday. That's the point - we're losing out on these people. They getting us at a ridiculously cheap price."

Later that night, I join the queue outside the Ballroom. Having negotiated the security persons, I find myself in a comparatively empty Ballroom. The place fills up eventually though, and by the time the Backdoor Blues Band start, everyone's crammed up near the front of the stage, ready to dance their bobby socks off.