New Zealand Student Politics

1980s-1990s

by W.S. McCallum

Ch-Ch-Changes

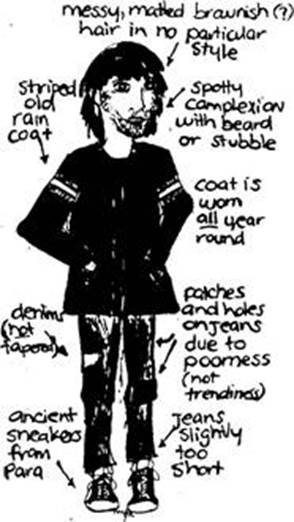

SCIENCE MALE (Still being seen)

(Illustration by Melissa Kerdemelidis)

Predominant trends, fads and sayings come and go with great speed.

It's often hard to remember how things have changed - especially over a short timespan.

Wayne McCallum looks back through the mid-1980s to rediscover what it was all about.

A lot has happened on campus since 1984, a year that kicked off with Rob's mob still running things. Merv Wellington had by then well and truly established his reputation as the most hated New Zealand Education Minister in history as a result of his flag-flying back-to-basics mentality; a position from which he may yet be toppled by the current Minister David Lange and his sidekick Phil "I was once a student radical" Goff. Still, in 1984, "user pays" education and student loans were as yet undreamt-of horrors. The only changes that had occurred since 1975 were essentially retrograde or an attempt to freeze things in time. Muldoon's price freeze was the perfect symbol of his period of rule - keep things the way they are for as long as humanly possible. And on campus too, things hadn't changed much since the seventies. The more hip postgraduates and younger lecturers still wore polyester flares and sweaters and listened to the Eagles or the Doobie Brothers. And members of that most visible of campus cults, punkdom, were still clinging to their equally faded "smash the State" ideals as they pondered over textbooks in the library. Seven years after 1977, Radio U's most played songs were still hoary old chestnuts like the Sex Pistols' "Anarchy In The UK", and other punk ditties thrashed for all they were worth. Yuppies at that stage were a still unknown phenomenon, the word itself not being widely understood and having no real application then.

Prior to the 1984 elections, the only excitement any student radicals experienced was protesting the arrival of the USS Whipple in Lyttelton, the last US Navy warship to call before the ANZUS row erupted. While Radio U stalwarts battled with the hassles involved in having their aerial pulled down by hoons no less than three times, the biggest shock experienced by the rest of campus was the raising of photocopier charges to 10 cents a page.

With Labour's election, it seemed a brighter new era was on the way. ''Consensus" became the new media buzzword at the big post-election roundtable conference as businessmen, politicians and trade unionists slapped each others' backs heartily and speakers paraphrased Hill Street Blues clichés like "let's be careful out there" as Government economic deregulation went into full swing. The cheery optimism has since been somewhat deflated by the odd stock market crash, the downfall of creative accounting ventures like Equiticorp and the collapse of small businesses due to takeovers and unregulated foreign competition. "Let's be careful out there" somehow seemed less relevant than other more pointed aphorisms like "cover your arse". While unemployment rose as well due to Labour's policies, trade unionists and workers alike gained the impression that "consensus" seemed to involve merely doing what the Government ordered and never mind the social consequences.

As share market prices suddenly began receiving prime-time TV airing on the 6.30 p.m. News, free market philosophies began blowing in the wind and Treasury officials came in out of the cold, commerce looked like the degree to take in 1985. Unfortunately, prospective commerce students were amongst the first to feel the squeeze that would become increasingly common in other faculties later in the eighties: faced with rising rolls, low staff levels and lack of funds to attract additional staff out of high-paying private sector jobs and into teaching, the commerce faculty began limitation of entry to courses. Such limitations were to spread to Stage One science and even arts courses as student enrolments in general began a rise that has yet to tail off. Total student enrolments at Canterbury have risen by 2,000 since 1984, a seemingly large growth, but small by comparison with the problems Otago University is experiencing: in the same period, rolls there have increased from around 5,000 to over 10,000. Nevertheless Canterbury's students now find themselves struggling to find an empty chair in the library as early in the year as April (in 1984, the library only filled up around exam time in the third term), parking their cars on campus lawns because there's no space in the car parks, and locking their bikes to trees and any other object for want of an empty bike stand. Worst of all is arriving for a lecture only to find yourself confronted with a packed lecture theatre and the prospect of sitting in the aisle on cold grey linoleum for an hour. Whether you wish to park your car, your bike or your posterior, there has been less space to do it at Canterbury over recent years.

Student politics became a bit more exciting in 1985. Radical activists once again mobilised to stop the NZ Rugby Football Union from sending a team to South Africa, and scenes reminiscent of 1981 occurred - people painting placards in the Student Union foyer, and a big march on Lancaster Park stadium was held on a dreary mid-winter Saturday afternoon to yell "shame" at a crowd of pom-pommed woolly-jersey rugby fans while a police helicopter hovered overhead.

Less militant but equally contentious was Radio U's proposal to the Executive asking for a loan to enable them to start FM broadcasting. The loan covered the cost of purchasing an $80,000 FM transmitter and aerial. A rather bitchy editorial appeared in CANTA complaining that if the Exec were giving away so much money, the least they could do was cough up the dough for a new Repromaster and electric typewriter for the Association's budding journalists. The result of that piece of editorialising was a protracted feud between student DJs and journalists. Radio U erected a sign on their door warning CANTA staff to keep clear and CANTA's editor continued raising objections at Exec meetings. In the end, both sides won - Radio U got its transmitter and CANTA its Repromaster.

The other area of contention and prolonged debate was the motion put forth to withdraw from the NZ Students' Arts Council. Angry noises had been made at Exec meetings for at least two years over the Wellington-based Council's tendency to sponsor acts which only toured North Island campuses and the validity of the University of Canterbury Students' Association (UCSA) paying $14,000 per annum for second-rate entertainment services that seemed to favour those living north of the Cook Strait. It was argued that the UCSA Cultural Affairs Officer could organise local acts to play on campus without dealing through a Wellington office, and for nationwide tours, things could be negotiated on an act-by-act basis, giving UCSA more leverage and control. The motion was passed and took effect in 1986: since then, the UCSA has rejoined.

(Illustration by Melissa Kerdemelidis)

On a less exalted level, student fashions were in the middle of a number of changes in 1986. The shaggy, permed, peroxide blondes on campus began discarding their legwarmers, the ultimate piece of redundant mid-eighties clothing and a mass fad among females who could at least claim to be health-conscious, even if they didn't attend the new-fangled "aerobics" classes (nb historians - the term "jazzercise" was passé by 1986; being something more associated with flabby housewives than the younger set). Socks also briefly went out of fashion, but perish your credibility if you hadn't put them back on by early '87. Madonna clones became a frequent sight too, as did their hair style - short, swept up, preferably blonde and with enough hair gel congealed in between the strands to keep it that way all day. Bobs started happening, and darlings, if you weren't laden down with a kilo or two of metal bangles, half a dozen necklaces (including the obligatory crucifix), big bulky earrings, (either circular or made out of modelling clay into bizarre things like ice creams) and even an ankle bracelet or two, then forget it! And on the topic of trendy jewellery, Maori bone carvings found popularity amongst Pakeha bourgeois liberals taking MAORI 101 and suffering from the guilt of white colonialism. But the biggest fashion shock of all was the invasion of the yuppie male at Canterbury. A pioneering example was Grant 'GQ' Mangin, an Exec member now gone but not forgotten for his gold lamé jacket and other stunning fashion combinations. Subsequently, the yuppie male has penetrated all corners of campus, with even those hallowed halls of post-punk alternative culture, Radio UFM, sporting four or five resident examples over the last couple of years. The days when the checked shirt was the height of male fashion at Canterbury are now gone forever.

Student media was a happening field in '86. Radio U became Radio UFM, successfully beating the opposition by several months to become Christchurch's first FM stereo radio station. Two Auckland-based student rags also appeared at Canterbury. The first was Campus News, a slender publicity sheet catering for yuppie steinie-drinking sports-car-owning ski bunnies, with the occasional short article squeezed in between all the colour ads. The other was University Times, a Moonie PR sheet financed and distributed by the Reverend Moon's student minions down from Auckland one wet August day. University Times only lasted one issue here, but Campus News soldiered on for a number of issues, suffering from an ever-increasing proportion of ads to a swiftly decreasing amount of readable copy. The existence of both were evidence of the sad deterioration of Auckland's Craccum over recent years.

Orientation '86 left some egg on people's faces too, sustaining a $22,000 loss that was only publicly announced months after the event. CANTA ran a "Guess The Orientation Loss" competition as a lead up to the announcement. Canterbury's Orientation is recognised as the best in the country, but has its occasional hiccups and bad administrators. The Neon Picnic fiasco of February 1988 was the work of two former Canterbury Orientation controllers from many years ago.

Some objectionable reading matter surfaced in the University Bookshop. In 1985, a letter to CANTA prompted the removal of Penthouse and Playboy from the shop's magazine section. Imagine the shock and dismay of the non-sexist male who discovered Playgirl still on the shelves a year later! An irate letter to CANTA ensued complaining about Playgirl and its sexist pictures of bronzed beefcakes with their "whizzers" hanging out. And while we're on that topic, 1986 was the year an AIDS-conscious Exec approved the installation of condom vending machines in both the boys' and girls' locker rooms. Definitely non-sexist.

The 1986-87 break saw Student Job Search operating with fewer offices, its Lower Hutt, Gisborne, Tauranga and Invercargill premises being closed down. The re-elected second Labour Government, a self-proclaimed "Education Government", showed its diminishing concern for student welfare by cutting out employer incentives to hiring student personnel in time for the 1987-88 holiday break. Going on the dole over the holidays is now the only option for over 2,000 Canterbury students who can't find work.

Homebrewing proved extremely popular amongst students as well as the rest of the populace, prompting the formation of Brewsoc by 1987. Worried brewery barons predicted the imminent collapse of the beer industry and began hyping up their public profile with a series of dreadful five-minute ads that were unavoidable if you went to the pictures at all. Students also served as walking billboards for brewery products, wearing Steinlager Blue and Green sweatshirts (in yuppie pastel shades of course), and also roll bags emblazoned with brewery logos were the in thing for boys whose old school bags war looking a bit worse for wear, as did yellow army surplus bags. Despite this, many brave first-year girls, then as now, continued lugging graffiti-covered TAZ school packs around, adorned with remarks such as "X loves Y", "Z is spunky", and the names of past top forty favourites, fading fast under prolonged exposure to sunlight. Acidwash jeans became de rigueur, a crotch-crushing fashion item appropriated by teens that was once only worn by skinheads (without the designer labels you understand). Stonewash items were still around but dropped a couple of notches in the trendy clothes stakes. Girls also got into wearing black kung fu shoes in a big way too, to the extent that they are now an almost universal item for female students. Amongst boys, the B-boy look followed in the wake of the Beastie Boys' chart success early in '87 - short hair, Adidas shoes and tracksuit accessories, baseball cap and large medallion (the latter is seldom seen on Pakeha males south of Auckland).

By 1987, Christchurch nightlife was broadening with the opening of glitzy meatmarkets like the Palladium and Xanadu, pubs were getting more ritzy as they refurbished for the yuppie clientele and even Nancy's and the Bush, student hangouts at either end of Riccarton Road, got the pastel tones splashed around their interiors. Saddest of all was the Gladstone, a magnificently ugly pub that was a fave students' haunt in the heyday of Christchurch punk. It now suffers the ignominy of being renamed "The Dorset Arms" and has been transformed into a genuine "ye olde moderne English pubbe". For those sick of cafe food and flat cooking, the advent of home-delivery fast food and a range of new restaurants meant better gastronomic fare.

Cycling gear was "it" in 1988, often among female students whose derrières hadn't touched a bikeseat since daddy bought them a Honda City in Seventh Form. Still, there they were, all black and white and checked and striped, in long cycling shorts. Real racing cyclists never wear underwear beneath such shorts, although I've never had the nerve to inquire if any of these young ladies follow the same practise.

Army surplus clothing also blossomed into a major trend in 1988 compared to its humble beginnings at the end of 1986 when it was worn only by a khaki trenchcoated minority, and those duck-murdering closet Rambos let loose every year during the shooting season. US Army surplus winter jackets have become a very common sight, to the extent that now surplus stores are diversifying into the retro-look "of another era". Retro-fashion also hit student parties too; seventies parties and strutting one's stuff in dodgy clothes to equally dodgy disco hits was one of the year's more bizarre trends.

But the most amazing transformation of all in 1987-88 was that the punks on campus acquired a new name. The oh-so-with-it Kiwi media, out looking for a new scourge of the nation's youth, began writing ill-informed accounts of "Gothic death cults". Fearful mothers from Gore to Cape Reinga began asking their clueless kids what a "Goth" was. Now, given a new lease of life under a different label, Canterbury's Siouxie Sioux clones with their jet-black Morticia/Elvira hairstyles, deathly white powdered faces, bright red lipstick and bluish eye shadow should remain a campus feature well into the nineties, along with their less imaginative monotonic black-clad boyfriends.

The hoon element on campus also enjoyed its share of the media limelight in 1988. Although by 1988 a generation of Canterbury's more legendary pissheads had passed into the workforce and the relative anonymity of Friday night swills with their workmates, various members of the engineering, forestry and commerce faculties succeeded in getting page 1-3 coverage in the Christchurch Star. UCSA President Sam Fisher was put in an embarrassing position when asked by journalists why such debauched activities happened in the amphitheatre and whether or not he supported them. In 1989, drinking horns have been notable only for their absence.

Apart from clothes, other items have become fashionable accessories for students since 1984. The highlighter pen is now a standard device for those too lazy to write down notes. Digital watches were fashionable, particularly amongst technophile science and engineering types who could bore you for hours describing all the things their crystal quartz jobs could do, but the backlash came in 1987 with the advent of the swatch and non-digital numbers. Yuppie girls wanted something bright and colourful, not cold and metallic, hence the current vogue for bright plastic straps, minimalist dials with no numbers on and a seconds hand consequently rendered practically useless. Bank machines have become so popular that a certain Ilam Road branch's front lawn looks like it has a garden party every Friday night, and even the library photocopiers now use tacky little plastic cards. The trick with such cards, whether library photocopier cards or bankcards, is to let everyone else apply for them and queue up endlessly waiting for a machine, while you stick to hard cash. I love watching the faces on people queuing with their plastic cards in the library while I waltz past and drop a couple of 20-cent pieces in the seldom-used coin-operated photocopier. Ditto for banks when you stroll in at five minutes to closing time past the queue at the ATM outside and go up to a bored teller twiddling his or her thumbs for want of something to do. Upon leaving, you smile benevolently at the suckers enjoying the wonders of waiting for modern technology while you pocket your cash.

Flats have gone relatively hi-tech too. A good many now have the latest in VCR technology sitting on top of a TV that may or may not work. Automatic washing machines are no longer something you go to the laundries to use and quite a few affluent people have an Apple Macintosh computer sitting in their bedrooms. You'll even find a microwave oven is a common sight in flat kitchens. The cooking may not be any better as a result, but at least it was done in a microwave!

1989 has been an ugly year for students not on the verge of finishing their degrees. The "Education Government" hastily steamrollered through the new Student Allowances at the end of 1988 without taking sufficient time to set up a bureaucratic structure to administer the scheme adequately. The already overworked Registry staff, faced with organising a record number of enrolments, have had to sweat their way through the added hassle of registering people for Student Allowances. As a result, there were no postal enrolments this year, a fact students weren't even informed of. The first Allowance payment has not only come out late, but hundreds of students have checked their bank accounts only to find no payment was direct credited. The main cause seems to be that the account numbers held by the Registry are all too frequently wrong and so their payments will be postponed till May. Other students have had five or more trips to the Registry to clarify various things only to find they too won't be getting paid until May because their tax code status has yet to be clarified. That the Registry is put in the position of having to handle tax codes (an IRD job they know little about) without IRD assistance, shows how badly thought-out this scheme is. On top of that, tax on allowances has brought their level down lower than the figure quoted by the Labour Government in 1988: that is, for those who have received payment and whose money isn't in some electronic limbo.

Student Loans were also sprung on students at the beginning of 1989, when the Labour Government declared on the first enrolment day that they would be operable from 1990. Many enrolling students had some hard thinking to do, often literally on the spot. Could they afford to continue next year and if they couldn't, why bother enrolling this year? Others on the verge of completing a degree in two years increased their work load this year to avoid paying out an extra $1,800 to the Government. Foreign students found themselves in a quandary too, their futures uncertain due to the sudden rise in projected course costs that will see them paying full fees for a completed degree. To many students, the "Education Government" seemed a dead loss by 1989.

Further fashion fads also surfaced in 1989. Ethnic yuppies are now the new breed - people with yuppie sensibilities but decked out in pseudo-hippy garb. Long flowing hair is compulsory for both boys and girls, vaguely ethnic clothing, and sometimes even paisley shirts (!) CV [the short-lived music clips TV show] currently presents two prime examples to your living room every Sunday. Then there are Gothic yuppies - the type who wear those trousers and skirts with black bats, skeletons and skulls on them. And who could omit the happy Acid House funsters? Only a year behind the times, a handful of young likelies appeared back from summer holidays proudly wearing their smiley face tee-shirts and buttons. Where there's a will there's a bandwagon....

Still, there are some things that never seem to change. Sickos molesting female students at night along Canterbury's ill-lit, shrub and tree-lined paths are a continuing consequence of the poor layout of the campus, the paths leading off to the Halls being particularly dangerous. Science students have an immutable and almost timeless style about them that seldom gets less than twenty years behind the times. The less fashion-conscious males amongst them still sport denims, old sandshoes, raggedy post-Beatles moptops, optional beards and horn-rimmed glasses, spotty complexions, and wear naff old synthetic raincoats with gaudy stripes down the sleeves. Science student style is not only timeless, it's non-existent.

And who could be more timeless than Canterbury's student-for-life Phil? Now nearing a decade on campus, Phil is not only the only person who knows all the ins and outs of Exec. regulations, but also the only person who can remember when they were passed. Phil's long haired, denim-legged, bare-footed, naff raincoat bedecked body is truly one of Canterbury's immutable fixtures and is about as likely to get up and venture forth into the real world as the James Hight Library Tower. No doubt in future years, the Lower Common Room will be renamed the Phil Memorial Room, in memory of those long-forgotten days when Phil and his overly verbal KAOS flunkies disrupted many a lunch hour with impassioned debates over matters of great consequence like the molecular structure of Spock's ears, while your grandchildren looked on in disgust.*

Originally published in CANTA No.9, 1 May 1989 pp. 7-9.

* Phil actually ventured into the real world a few years after this article was originally published.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

August Divide

VUWSA building

W.S. McCallum

Drama. Excitement. Conflict. Monotony.

It was all at the NZUSA August 1989 Conference in Wellington, as Wayne McCallum discovered.

The New Zealand University Students' Association (NZUSA) August Conference started lethargically at the Victoria University of Wellington Students' Association (VUWSA) on Saturday, August 26th 1989 at 9.13 a.m. Andrew Little, NZUSA's President, seemed somewhat bemused at the 13 minute delay in starting due to late arrivals, the listlessness of those present and the fact that only Canterbury's and Otago's representatives had delegate lists prepared. His opening address served as a short backgrounder on recent developments in the Student Loans saga and he commented on the strength, improved representation and organisation of the NZUSA since its internal disputes back in 1986. This assumption was to be severely tested in the Closing Plenary. The Federation Report was received at 9.28 a.m. Andrew Little asked for questions or comments but none were forthcoming, mainly due to the fact that many delegates hadn't even read the Report and were busy belatedly thumbing through it even as he spoke.

Following that, Andrew Little proposed a number of changes to the Conference timetable and general confusion ensued as a number of tired and slightly grumpy student politicians, with consequentially short attention spans, coped with the mental strain of trying to work out the new schedule. The 9.00 am conference start time was taking its toll. Little opposed a move from Auckland to reintroduce a Women in University meeting that had been cancelled for want of guest speakers, on the grounds that no prior notification had been received. Having just proposed certain impromptu changes to the timetable himself, his argument sounded a bit shaky to many present. A women's meeting went ahead informally that afternoon anyway.

Around 10.25 a.m., the Student Allowances workshop opened, and proved to be informative and well run. The differing methods of payment used by various campus administrations were assessed, as were their liaison (or lack thereof), with student representatives over the flood of foul-ups caused by the overly hasty introduction of the allowances. It was assumed students were now stuck with the scheme and would have to work on improving it from the inside. The overall portrayal of the scheme at the meeting was highly negative, with people giving details of various administrative horror stories, stopped payments, bounced cheques and the like.

1.38 p.m. The Campaign Review, run by NZUSA's Vice-President Frank McLaughlin, attracted a slightly larger audience than the Learning For Life discussions taking place next door. Part of the attraction may have been the promised arrival around 3.00 p.m. of a TVNZ camera crew to film the meeting for the Six O’Clock News. Each campus gave a rundown on its activities and the general impression was that things were at a low ebb after the effort of organising July's mass marches. The Lincoln representative's remark that things were "pretty dead at the moment" seemed to sum things up and lack of activity was compounded by the August holidays and the lack of a clear Labour government statement on student loans following its recent leadership reshuffle. Recent meetings with the Labour Government and new government incentives to banks prompted four trading banks to come out in support of student loans. Although they were reluctant to name themselves publicly, it was assumed that the four banks in question included Westpac, National, and the ANZ.

Frank McLaughlin stated that for the third term, students would mobilise against these banks to persuade them it was unwise to lend support to student loans through a high profile campaign of considerable nuisance value. Tactics are to involve blitzing money machines by depositing green rags. Each such deposit costs the banks around $1.50 in administrative and handling costs. Other ideas mentioned were holding up tellers by transferring amounts as small as five cents between individuals’ cheque and cash accounts. Doing so can cost banks around $5.00 in overhead costs.

Around 4.00 p.m., while David Novitz was speaking downstairs on academic freedom, upstairs two meetings were taking place which would lead to disagreement and animosities spilling over to the Sunday Closing Plenary. The first meeting of the Finance Commission was discussing the proposed $35,000 levy for 1990 to Nga Toki, the autonomous Maori student group affiliated to the NZUSA, in the Upper Common Room. Across the landing, in the Hunter Lounge, a Nga Toki member was addressing an unscheduled meeting on the Treaty of Waitangi and the NZUSA's position on it. Both questions were to result in a healed clash at the Closing Plenary.

Sunday

Sunday morning started off even slower than Saturday did with proceedings not opening till 9.20 a.m. Canterbury's Suze Wilson and Charlotte Denny stood unopposed for NZUSA President and Vice-President respectively and were both duly elected.

The second Finance Commission meeting took place in the Upper Common Room at 11.37 a.m. The NZUSA's Projects Fund was set at $80,000 for 1990. Andrew Little proposed that if future February Workshops and August Conferences were scaled down, a cost of $8,000 could be saved. It was decided to examine this further as there was some doubt whether reducing the effectiveness of these two national meetings was something that should be done given the smallness of any economies. Any decision was held off until January.

Then came the issue of the Nga Toki levy. Suze Wilson, Canterbury's President, opposed a rise in the existing $35,000 figure to a full funding of $75,000 for Nga Toki. She stated that if so much money was to be given by NZUSA, then Nga Toki should have its status changed from that of an autonomous body to a standing similar to that of groups like the NZ Students Arts Council. A proposal was moved to have two budgets set before the Closing Plenary - one with a $35,000 levy and one with a $75,000 levy. Andrew Little responded by saying that the Federation Executive had already decided $75,000 wasn't feasible. It was stated Nga Toki had now decided not to apply for any alternative sources of funding until NZUSA has guaranteed a minimum $40,000 levy. Suze Wilson attacked this, saying that NZUSA had already organised alternative funding sources for Nga Toki, the latest of which was a Lottery Board Grant they had refused to apply for just the preceding Thursday. She wondered where any Nga Toki impetus to search for other funding was going to come from if they already had NZUSA supporting them to the tune of $40,000. She continued by saying that Nga Toki was trying to have it both ways, and cast into doubt Nga Toki claims of autonomy from NZUSA. The motion for the increase was rejected, with Waikato abstaining. To close, the Finance Commission passed a NZUSA levy of $5.65 per student for 1990.

The Closing Plenary commenced at 3.45 p.m. and was very businesslike. Most people wanted to get everything completed as smoothly as possible so everybody could go home, but it wasn't to be. Things ran fairly smoothly, and then the Finance Commission recommendations came on the table and very rapidly all hell started breaking loose.

In a surprise move, Otago put forward a shadow motion concerning the Nga Toki levy. They wanted the levy anchored 5% higher to account for budgetary variation and called for better and open discussion between NZUSA and Nga Toki. Andrew Little objected from the chair, pointing out such a motion would be unconstitutional in dictating to the proceedings of a future general meeting. At 4.32 p.m., Otago called for a ten minute break to get its act together.

At 4.58 p.m., we were still waiting. Perhaps the most interesting observation of the Conference is that student politicians work on a different time scale from you and I. A five minute break invariably involves anything from seven minutes to a quarter of an hour, while a ten minute break can be as long as half an hour. By this time, the atmosphere was getting tense. Little factions were huddled around the Hunter Lounge muttering to one another. Suze Wilson was visibly hacked off. The four Nga Toki members sitting in on the Plenary are gathered on one side of the room. Lawrence, their leader, having stalked back from the table where Andrew Little and a couple of other old NZUSA hands are talking, yells out at them: “You're leading us up the garden path by promising us another hui - get your facts right!”

5.02 p.m. Massey representatives want another 'five' minutes. The Plenary reconvenes at 5.11 and Massey triumphantly intervenes. Female supporters chuckle jubilantly in the row behind him as Neil Morris, their President Elect, gleefully reads a clause from the NZUSA Constitution which allows the Conference to be adjourned till September 15th.

The motion is an attempt to pressure NZUSA into renegotiating with Nga Toki in the interim. Massey has joined Otago in blocking the budget and Auckland, with the heaviest voting weight, is siding with them too. Andrew Little objects to the motion saying any hold-up in passing the NZUSA budget for 1990 will interfere with the ability of member campuses to decide their own budgets. Massey says the budget must be reconsidered and Otago adds that further negotiations must be conducted with Nga Toki. Little wants the budget passed immediately and Lincoln, Canterbury and Victoria support him, but lose out to the greater voting weight of the other side. Reluctantly he declares the Conference adjourned till September. By now there's some uncertainty as to what to do next. Copies of the Constitution have materialised around the room and after some frantic thumbing through them, the motion is declared open to discussion.

Suze Wilson accuses Massey of using Constitutional procedure to obstruct NZUSA and points out there's nothing to stop them postponing the meeting into 1990. She also accuses Massey and Otago of going back on Finance Commission discussions they had previously agreed to.

Auckland moves that a Nga Toki representative be granted speaking rights. There's more constitutional page-turning and the motion is rejected.

Andrew Little states he wants the Finance Commission reconvened on the spot and threatens legal action forcing the August Conference to complete its business no later than August 31st. At 5.39 p.m. he declares a half hour adjournment.

By now Suze Wilson is overwrought with anger and frustration at Otago's hijacking of proceedings with their shadow motion and the incongruity of their call for more open dialogue between the NZUSA and Nga Toki when Otago played no active part in recent funding negotiations.

At 6.14 p.m. the Finance Commission is reconvened after Otago withdraws its shadow motion. Two women from Nga Toki have a good laugh at the sight of Pakeha student politicians frantically rushing around setting up a conference table. Few others see the joke. As chairs are brought in and set up, the light outside is noticeably fading. More than one delegate will miss their flight home tonight. Suze Wilson resupports the $35,000 levy to Nga Toki, adding that NZUSA's raison d'être, its Projects Budget, is only $80,000: "If that's not evidence of NZUSA's commitment to Nga Toki, I don't know what the hell is!" In opposition, a $45,000 levy is proposed on grounds that none of the Federation Executive can fathom. Andrew Little warns that such a large jump from previous levels of funding could split the NZUSA and asks just where the extra $10,000 is going to come from. A comment is made from the other end of the table about the danger of NZUSA giving in to 'sector groups', a label which causes Lawrence from Nga Toki to explode on the sidelines. Another warning is made that NZUSA could have a repeat of 1986, when the question of Nga Toki's status with NZUSA nearly split it apart. At 7.00 p.m. a motion to stick to the $35,000 levy is defeated by Auckland, Massey and Otago. The opposing motion supporting a $45,000 levy also loses out when John Craig from Waikato abstains on the grounds that he hasn't heard any reasonable argument for it.

So now there's no budgetary allocation to Nga Toki. What to do? The next step is to rescind the budget altogether, but Auckland gets cold feet. By 7.16 p.m., the $35,000 levy is reapproved unanimously. In the space of just two hours, members of the NZUSA steered the organisation up to a constitutional precipice over Nga Toki funding, left it teetering on the brink, then pulled their weight back when they started getting vertigo.

7.26 p.m. and the Closing Plenary is back underway. Massey withdraws its motion to postpone proceedings; the budget is approved. Then comes the next crunch: a motion arising out of the Waitangi discussions on Saturday afternoon, concerning the integration of the Treaty of Waitangi into the NZUSA Constitution. Suze Wilson is once again in the thick of it, holding off an interjection from Nga Toki's Lawrence, as she spells out her opposition to the motion on the grounds that the Treaty is between the Crown and the Maori people - NZUSA belongs to neither party, but can support Maori claims.

Lawrence is by now getting very agitated and Bruce Cameron from Massey asks that he be allowed to speak. The right is granted and Lawrence proceeds to offer a homespun metaphor on the Treaty, involving a $1,000 debt on a used car. Not everyone understands exactly what it is he's trying to say, but many are taken aback when he implies NZUSA will either have to give Nga Toki 50% representation or wash its hands of any claim to biculturalism in 1990. Maori students currently comprise 3% of the student population.

The original motion is rephrased, proposing "that workshops be held in February 1990, to investigate the implications of acknowledging the Treaty of Waitangi in the NZUSA, Constitution...". It is passed.

The Plenary finally closed some three hours later than expected at 8.07 p.m. If those last hectic hours of the August Conference are any indicator, the proposed 1990 February Workshops could result in a mother of a showdown over Nga Toki's status within the NZUSA and NZUSA's own relationship with the Treaty of Waitangi.

Originally published in CANTA No.22, 4 September 1989 p. 9.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1989.

The Dunedin Rampage

The Dunedin student riot on Saturday 14 April 1990 caused quite a stir, and created many vague, often conflicting accounts of who was to blame. Wayne McCallum attempts to reconstruct the sequence of events with the help of an eyewitness.

Just exactly what did happen on the evening of Saturday 14 April in Dunedin is still open to a lot of speculation. TVNZ's coverage of the riot that weekend consisted of a few split-second camera shots of people standing or running around, with a voiceover that said "Explanations for the cause of the riot are still a little confused". An edited interview with Senior Sergeant Allan Strang of the Dunedin police, squarely placed the blame on students: "We stood back and gave them the chance to go. They advanced on us and two of my staff got dropped". A student interviewed for the same video clip blamed the police: "There was no aggro, there were no fights. And then the cops turned up".

Press coverage of the riot wasn't particularly detailed either. All the Sunday papers had been caught on the hop as the riot had taken place after they had gone to print on Saturday evening. Given the chance, the Sunday tabloids would have screamed it from page one, but they had no such luck. The Press gave the event front page coverage on Monday morning, but its Press Association release wasn't particularly detailed either. Precise details as to why the riot occurred weren't given. As the riot started around 9.00pm, and press and TV reporters didn't arrive on the scene till after 10.00pm, it's safe to say that they didn't really know what happened.

The following account of the riot is based on an eyewitness account. A former Canterbury student, who I'll call Alan, saw the events leading up to the riot, and the first two and a half hours of it. Although not claiming to have seen everything that took place, his account is more detailed than anything I've seen in the mainstream press at the time of writing. He himself admitted that much of what happened formed a blur. There were so many things happening at once that a complete account of what occurred is nearly impossible. As the police were doing their best to split the student crowd up into little groups, there are few, if any, people who can claim to have seen everything that happened anyway.

Alan started off his Easter break on Thursday afternoon. He and his mates were part of the Under 500 car rally to Dunedin which coincided with the Tourney. About 45 cars purchased for less than NZ$ 500 left Christchurch from the Bush Inn around 1.30pm, laden with anywhere from four to twelve people per vehicle. Alan's car left late, because of mechanical trouble, about 3.30pm.

As they drove to Dunedin, they followed in the wake of the rest of the rally, and so missed what Alan described as "the carnage". There were five planned pub stops on the way, which reportedly resulted in a certain amount of vandalism. Alan's car was warned off from one service station where they had stopped for petrol. The owner gave them an earful about how some preceding students had stolen a toilet seat from the rest rooms and had chundered everywhere.

They arrived in Dunedin at about 9.00pm that evening. Alan said some rally cars got pulled over by the MOT [traffic cops] just before Dunedin. Only forty cars arrived in Dunedin due to breakdowns. The worst breakdown involved a van carrying fifteen people who had to hitch rides off other cars in the rally.

Auckland University students on the train to Dunedin also caused a bit of a stir. Eager to do a follow-up item or two after two Auckland students had jumped off the ferry on Thursday morning and swam ashore at Picton, the TV people dispatched their camera crews to follow the Auckland students' antics. They got all the raw material they wanted - students dropping their trousers, vomiting, and making general nuisances of themselves.

Alan described Friday night in Dunedin as being very quiet. All the pubs were closed because it was Good Friday. As a result, no one had much to drink except a handful of lucky students in the know who found a hotel proprietor willing to make a few extra dollars on the side. The only incident occurred at the Otago University Students' Association "'hop" (or "stein" as they're called at Canterbury). The three hops scheduled over the Easter Tourney had been oversold. Alan told of $10 ticket holders (able to attend all three hops), getting a much better deal than those who had decided to go for $7 single night passes. Door sales were promised, but because too many people had been sold tickets already, students were turned away. Those who did have $7 tickets were, in many cases, let in. But imagine their dismay when they were shunted into a side room, had their tickets taken off them by bouncers, and were pushed back out into the crowd. A few frustrated people tried to overturn a DB beer tanker, but the presence of bouncers dissuaded them.

Saturday also started out looking fairly peaceful. Most of the Under 500 participants hadn't come to Dunedin for the sport, so they spent the day drinking and socialising. Alan arrived at the Gardens Tavern, Castle Street North, at about 11.00am and found the pub full with student clientele. He said the Gardens did a roaring trade that day. The place was full right through the afternoon, with around 200 students present. Alan, who works as a barman himself, said they would have made "tons of money" that Saturday.

The drinking stopped at 8.45pm, after Dunedin police ordered that the pub be closed, with 600 students present. They had three principal reasons. One was the presence of a large number of underage drinkers. The other was a clause in the Sale of Liquor Act which states that alcohol shouldn't be served to intoxicated people. Another reason mentioned by the police and TVNZ was overcrowding in the pub.

Alan said that, prior to the closure, the Gardens was about as peaceful as you can expect a pub to be on a Saturday night. A number of inebriated students had dropped and broken glasses, but there was no concerted vandalism, and no brawling in the Gardens prior to its closure.

When 660 students found themselves turned out into the street before 9.00pm, some decided to head over to the Captain Cook Tavern in Great King Street, on the other side of Otago University. When they found it too had been closed, they headed back to the Castle Street/Dundas Street intersection by the Tavern. Alan said that it was around this time that "all the trouble started for the police". The attitude in the crowd was "you kicked us out of the pub, so why not just party in the street?" The policemen present at this stage kept their distance. They were heavily outnumbered, and called for reinforcements.

Students totally filled up the Dundas Street/Castle intersection. Those who had been partying at the Gardens Tavern had gone down the road to join a party in Castle Street. TVNZ claimed there were 1,000 students. The Press claimed there were 1,500. Alan, present at the time, said there were 4-500 people from the pub, who mixed with a few hundred more from the nearby party. He said that, at its highest, the crowd was no more than 1,000.

Alan said three cars had been overturned at the northern end of the intersection by the Castle Street partygoers prior to the arrival of the Gardens crowd. Students, described by Alan as being from all campuses, including rally and Tourney competitors, as well as living in the neighbourhood, began pelting the police present with glass. It was the beginning of a hail kept up continuously by 50-60 students throughout the riot. A police car which approached the intersection down Dundas Street from King Street was forced to turn back under a shower of glass.

Despite the police presence, it was clear that the students weren't going to disperse. Instead, they sat on the intersection, yelling "Fuck the pigs, no fees!" [a strange amalgam of anti-police sentiment and hostility to education fees].

At 9.15pm, Alan said there were between forty and fifty police present. The Press stated there were 47. And 20 were kitted out in riot gear. The others wore ordinary uniforms. In some cases, the police were in no more than shirtsleeves. Alan commented “They must have been short of manpower”.

Included in the police present by 9.15pm was a dog squad. Alan said that it was the two dogs which really got people moving when the police closed in. TVNZ claimed twelve students had to go to hospital to have dog bites treated. The Timaru Herald (16 April 1990) claimed eleven students were treated for dog bites.

A major contribution to the tension at the intersection was a blue Mini which had been overturned on its left hand side. The petrol tank leaked its contents out through the filler cap and flowed about 20 metres down an adjacent gutter. It was claimed in The Press that a deliberate attempt was made to set this and another car (which Alan didn't mention) alight. Alan said he didn't know if the Mini catching fire was deliberate, or just an accident. Whichever was the cause, one of the numerous smokers in the crowd tossed a cigarette butt in the gutter, and the trail of petrol there caught fire. The flames spread from the gutter, back to the source of all the petrol - the Mini's petrol tank. The back end of the Mini went up in flames, but there was no Hollywood-style explosion. The sight of the Mini on fire apparently agitated the police considerably. "That really freaked the police out," Alan said. Both police and students backed off from the flames.

Around 9.15pm, the police decided to move in and clear the Dundas Street/Castle Street intersection. They approached from three sides - up Castle Street towards Otago University, and from both ends of Dundas Street. By then an ambulance and a fire engine had arrived. The police held them back. It turned out that the fire engine wasn't needed to extinguish the Mini, as the flames died out there of their own accord.

Under police pressure, the student crowd was pushed back up Castle Street, in the direction of Otago University. As they fell back, staff at Selwyn College locked their gates and secured their buildings to keep students out.

Once students had been pushed out of the Dundas Street/Castle Street intersection, the police made at least four attempts to disperse them from Castle Street. These attempts were unsuccessful. As they advanced up Castle Street, they got pelted with glass, not only from some 3-400 students occupying the street, but from some of 6-700 sheltering in properties alongside the street. Numerous students stood on the roofs of flats down Castle Street, throwing tiles and glass. The police were unable to reach them. Others climbed up trees or hid in bushes to avoid being caught by police or dogs.

Material thrown included full cans and beer bottles. A picture of one police dog handler who had been hit by a dart was shown in The Press. Alan said that students on the street were receiving active support from student flatters living in Castle Street. Students were going into flats to fill bottles up with tap water, and then taking them outside to throw at the police.

By 10.00pm, the crowd had pushed the police back up Castle Street, past the Dundas Street intersection. The situation was fairly chaotic. Some student flatters had hauled rubbish and even furniture out in front of their flats and started bonfires with them. Students had been bitten by police dogs, and batoned by police. The police, in turn, had been on the receiving end of thrown bottles and glass, along with a variety of other objects. Queen's "We Are The Champions" was blaring out on to the streets from a stereo in a flat up the northern end of Castle Street.

About this time, Alan saw one of the arrests which took place that weekend. A student on a Castle Street property between Dundas and Howe Streets threw a bottle which hit a policeman's riot shield. The student was spotted and three policemen ran on to the property and beat him before hauling him away.

There were still 7-800 students on the street between 10.00 and 11.00pm. After 10.00pm, the police divided the students into two groups of about 3-400 people each, when they moved back to take the Dundas Street/Castle Street intersection. One group was pushed up Castle Street, back towards the University. The other group was pushed back off the Dundas Street/Cumberland Street intersection. Alan was with this second group, and so he didn't see what happened to the crowd in Castle Street. The group he was in dispersed across the North Grounds. Alan went too. He said that by that time the police "were just walloping anyone who came too close. I just had my hands over my head. If they saw anyone near them with their hands down, and thought you had a bottle, you'd get it".

Alan left the scene around 11.15pm. When he drove out of town around 2.00am on Sunday, there were still people out in the streets, along with police and a fire tender.

Originally published in CANTA No. 8, 23 April 1990 pp. 16-17.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1990.

Guilty of Tunnel Vision

Has the New Zealand Students' Association failed its members?

Education protest rally in the Square, Christchurch, 1991

W.S. McCallum

Following its restructuring in 1986, by 1991 the New Zealand University Students' Association had moved sharply rightwards. Once regarded as a progressive force within New Zealand society, the NZUSA was confining itself to lobbying on education issues. So what went wrong?

In 1989, journalists from the International Union of Students (IUS), an organisation based in Prague, visited Australia and New Zealand. While in Wellington, they paid an impromptu visit to the office of the New Zealand University Students' Association (NZUSA). Judging from their account, the journalists were perturbed by their reception, which displayed touches of Cold War paranoia: credentials were asked for, it was inquired who funded the IUS; whether it really was an international body; and what its aims were. This ignorance of the IUS was superficially odd: the body was formed in 1946, and was the subject of periodically heated debate within the NZUSA (again, due to its East European origins) from the 1940s to the 1960s. History aside though, it was not surprising, in their article on student politics in New Zealand, that the IUS reporters characterised the NZUSA as being parochial in its outlook.

NZUSA parochialism transcends mere ignorance of the IUS. As a result of its concentration on education lobbying in the late 1980s, the NZUSA has become ignorant of, and unresponsive to, international student politics. In recent years, apart from the South African Scholarship for black South African students which, as it was founded in 1975 is a legacy of a more socially committed generation of student leaders, the NZUSA has displayed little concern for students rights issues overseas. The only student repression which has prompted public condemnation from the NZUSA's members in recent years was the Tiananmen Square massacre, arguably an event too big to ignore. Closer to home, the harassment of Fijian academics and students at the University of the South Pacific has failed to draw similar condemnation. Again, in terms of NZUSA’s historical links, this is surprising. Not only have Fijian students been NZUSA members for decades, also in the late 1960s, the NZUSA supported the founding of the USP, donating books to its library, and assisting in the establishment of a students' association there.

The narrowness of the NZUSA's concerns is also evident in its lack of response to New Zealand social issues other than educational lobbying. Since 1986, its member associations have failed to continue the sort of activism they once supported over issues such as sporting links with South Africa, and nuclear ship visits. The official line of reasoning against such activity has tended to be that individual students should decide their own responses to such issues. The exception to this rule is that student politicians show no such hesitation when it comes to articulating supposed student opinion on various educational issues. If student leaders were to abdicate this responsibility, it might he asked what political role they would play at all.

And an abdication of responsibility it is, given past NZUSA policy of speaking out on a broad range of social issues that affect New Zealand society. This 1969 comment by the NZUSA in its defunct review Focus, is typical of its former stance:

"There are a great deal of issues within New Zealand which affect students closely apart from educational and financial problems. Students as a group are affected in particular ways by legislation, social conditions etc., which also affect a wider section of the community […] NZUSA activity can have wide repercussions on national issues", (Focus February-March 1969)

In contrast, the NZUSA's silence in the late 1980s over the Labour Government's erosion of the welfare state was notable. Unless tertiary education was directly involved, the NZUSA was uninterested in actively opposing Labour policies. In an interview with the Canterbury student newspaper Canta (7 March 1988) Ann Webster, the NZUSA Vice-President in 1988, expressed the belief that “now that our priorities are reorganised and we are focusing on education and how university affects students” student politicians would be able to discard their former “left-wing fanaticist image”. This reluctance to be seen as "trendy lefties" is widespread among student leaders. On a national and local level, they have shown an unwillingness to form links with trade unions, health lobbyists, unemployed rights groups, and other organisations.

For example, in September 1990, an unemployed rights representative came into the Canta office at the University of Canterbury Students' Association, where I was then working as the newspaper's editor. He had gone to the UCSA President, Chris Whelan, to solicit student support for a benefit cuts rally in Latimer Square and was puzzled by the lack of interest Whelan had displayed. I attributed this to the President's comfortable middle-class origins, and felt too guilty to explain that student associations were no longer interested in social issues like opposing benefit cuts. Likewise, Chaff, the Massey university students' newspaper, reported a disappointing lack of response to the Palmerston North Workers’ Unemployed Rights Centre when it attempted to raise student support for a protest against the Employment Contracts Bill (Chaff 13 March 1991). And Canta reported student leaders' lack of concern at the NZUSA February 1991 Workshops when Robert Winters, Youth Officer from the CTU, outlined the effects of the Employment Contracts Bill. Those present were more concerned with the effect the Bill would have on them as employers of student association staff, than in the opportunities the legislation would provide employers with to exploit part-time student labour (Canta 5 March 199l).

Such incidents are not isolated ones. They are symptomatic of broader student uninterest which stems directly from a lack of student leadership and association policy on such issues.

In the mid-1980s, NZUSA politics experienced a fundamental change in nature. Critics of the NZUSA accused it of becoming sidetracked from immediate student concerns. such as bursary payment levels and internal assessment. There was also criticism of the number of personnel employed in the NZUSA Wellington offices. The National Executive then included seven elected members, and six staff worked in research and clerical positions. Staff salaries comprised 43% of the NZUSA's budget in 1986, and there was a $15,000 deficit projected that year. Conservative student leaders wanted to lower the level of the levy each student paid to the NZUSA. Reducing the number of NZUSA staff was the most obvious cost-cutting solution.

In the restructuring implemented in August 1986, the NZUSA was reconstituted as a federal association, with it President and Vice-President being elected to represent the views voted upon by constituent associations. Maori representation was re-established in a separate national Maori student body, Nga Toki, which remains subsidised by the NZUSA. The overseas student representative, Maori representative, and women's representative were eliminated from the new Federation Executive and the office staff was reduced to one clerical worker.

The restructuring reduced staff expenditure from 43% of the NZUSA's budget in 1986 to 29% by 1989. Over the same period, the research and projects funds rose from 16% to 33% of the budget, an important step in increasing education lobbying. Students' associations were also happy to see their levy fall from $9.60 per student in 1986 to between $5 and $6 in 1991, although a national increase in the student roll over that period also contributed to lowering the per capita levy required. The restructuring failed to eliminate the NZUSA's deficit, which stood at $42,234 by the end of 1989.

These economies came at a price. With a reduction in NZUSA staff, the three left could do little more than education work. The attention formerly devoted by individual staff to particular policy areas was now a thing of the past. Perhaps the group most adversely affected by the loss of an NZUSA representative were overseas students, who are only represented on four out of seven local student association Executives, and who have no single organisation such as Nga Toki to represent them independently at national level. The Labour Government's introduction of full course fees for overseas students is one case where such a voice could have been useful.

The staff cuts did allow the NZUSA to concentrate more money and attention on education lobbying, but with varying degrees of success. The need for the NZUSA to do so was more pressing under the Labour Government than it had been for many years. The education system was one of Treasury’s many targets for change listed in its 1984 Economic Management manifesto. The education system was described as a “poor performer”, although this assumption was based more on New Right dogma than on statistically justifiable evidence. The humanist view that universities were centres for intellectual development and the expansion of knowledge was discarded by the Government in favour of an outlook that regarded them purely in terms of what they could offer local capitalism. Universities came to be regarded as inefficient, costly suppliers of personnel who weren't tailor-made to suit employers’ demands in the labour market.

To its credit, the NZUSA was active in opposing this outlook. It criticised the Labour Government's attempts to reduce spending on tertiary education. In 1989, Labour scrapped ill-conceived cost recovery schemes such as a tax on graduates, and a student loans scheme coupled with greatly increased tertiary fees, in the face of wide-spread opposition, and the dawning realisation that these schemes were impractical. The NZUSA played a significant part in opposing these schemes up to and during 1989, through marches and submissions to the Government.

1990 was a less successful year. Following the failure of its more elaborate proposals, the Labour Government simply raised the up-front fees students had to pay. In 1989, most students paid less that $200 for a year's full-time study. In 1990, the charge was raised to $1,250. The NZUSA failed to organise a protest involving nation-wide delayed payment of fees prior to the October election, due to student resignation to the fees, student fears of being disenrolled, and lacklustre attempts by students’ associations to mobilise their members. Only three campuses, Auckland, Otago and Lincoln, mobilised after obtaining the support of a minority of their students for delayed payment. The NZUSA learnt the hard lesson in 1990 that the most personal involvement it could expect from students was their participation in marches - they were not prepared to risk their educations in the struggle against government policy.

The NZUSA distracted attention from the failure of the anti-fees campaign by declaring a court action against the Labour Government in August 1990. The NZUSA contended that the Government had breached the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights when it decided to drastically raise tertiary fees. Whether the NZUSA will force a fees reduction by arguing a technicality such as this remains to be seen; the legal action is still in progress and could be stalled by the National Government for many months. Student representatives at Victoria University in Wellington criticised the cost of the action - anywhere up to $30,000 by their estimate. The NZUSA’s activities budget for 1991 was $75,000. The case will be a drain on finances that could have been employed in more public forms of protest. [Author’s note: the court case eventually petered out, having achieved nothing.]

In 1991, up-front fees were raised to $1,320 for a year’s full-time study. National’s Education Minister, Lockwood Smith, pledged to scrap the fees instituted under Labour by 1992, and to substitute a new scheme called Study Right, which is essentially a voucher system allowing for four “free” years of education to students for their first degree. What will become of this remains to be seen [nothing as it turned out: student fees, along with a subsequent loans scheme, remained under both National and subsequent Labour Governments…], but the NZUSA’s response will essentially be one of behind-the-scenes lobbying on the technicalities of National’s proposals.

In its 1990 election guide for students, called Hobson’s Choice, the NZUSA set out its vision for education in the 1990s: “If NZUSA’s vision for education could be encapsulated in three words, those words would be Access, Equality and Quality”. Opposition was expressed to raised fees and the spread of limitation of entry within universities due to shrinking budgets, as these would shut out the disadvantaged people in New Zealand society:

“Equality issues are part of the access debates, because we don’t think your age, wealth, gender or ethnicity should mean you miss out on education. But once you’ve made it into the system, we want to make sure everyone gets a fair deal. We want to see a greater commitment and effort by the universities to recognise the needs and perspectives of women, Maori and Pacific Island students, and students from backgrounds under-represented in the system.”

Sadly, the NZUSA is guilty of tunnel vision. With the National Government’s introduction of benefit cuts, and its deregulation of the labour market, the disadvantaged portions of New Zealand society are going to be even less likely to afford a university education than before. This remains an underlying fact of university access issues which the NZUSA has failed to address. This failure is the reason why the NZUSA has not set policy opposing the dismantling of the welfare state, or actively co-operated with pressure groups outside the education sphere. The NZUSA is only interested in supporting the rights of the disadvantaged “once you’ve made it into the system”. Given how few of these people make it to university already, it might be asked whether the NZUSA is adequately representing the rights of the disadvantaged at all.

Originally published in The New Zealand Monthly Review August/September 1991 pp.17-19.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1991.

New Zealand Students’ Arts Council To Be Disbanded

In the first week of April 1992, the New Zealand Students' Arts Council (VZSAC) publicly announced that it was to be disbanded in December 1992.

The twenty year-old organisation, funded by New Zealand's seven university students' associations, has been instrumental in organising national tours by musicians and other performing artists around university campuses. National tours of art and photography exhibitions, student orientation festival bookings, and annual campus radio and student journalists workshops in Wellington have also been coordinated by the NZSAC.

Despite the NZSAC's invaluable contribution to student arts and the New Zealand arts scene in general, discontent with the association's performance has regularly surfaced among contributing students' associations over past years. Differences have surfaced over the issue of whether or not individual campuses were receiving value for the money they contributed to the NZSAC. Perennial complaints have included accusations that the NZSAC bureaucracy in Wellington is top heavy and is unjustifiably expensive; and that some of the NZSAC's sponsored acts never make it to smaller campuses or south of the Cook Strait. In the mid-1980's such dissatisfactions led the University of Canterbury Students' Association (UCSA) to call a referendum among its members on whether it should pull out of NZSAC.

The NZSAC has largely been able to weather such criticisms in the past through internal negotiation and reorganisation. Some campuses which felt themselves to be neglected by the NZSAC have been prompted to reorganise their own cultural fare to a greater extent than in past years. The UCSA has had its own student activities co-ordinator, Bats' bassist Paul Kean, working full-time since 1990. Similarly, the Otago University Students' Association (OUSA) has had Stephen Hall-Jones, co-editor of Jester magazine, as its student activities manager for the past seven years. The OUSA's and the UCSA's campus entertainment has benefited from such full-time coordination to the extent that their cultural programmes are arguably more varied and of better quality than elsewhere.

Other students' associations have struck with the traditional arrangement of appointing part-timers to run student entertainment and relying on the NZSAC to supplement this fare with touring acts. This reliance on novices has on occasion proved a recipe for disaster, due to the inadequacies of the campus organisers appointed, or due to the time limitations placed on them in attempting to organise entertainment and trying to fulfil other personal obligations such as university studies. The Auckland Students' Association (AUSA), for example, lost in excess of $60,000 in running its orientation programme in 1990, an event described by the Auckland student newspaper Craccum (30 April 1990) as "one of the worst results in the Association's history".

This year the Victoria University of Wellington Students' Association (VUWSA) Executive, after having had bad experiences with its orientation controller in 1991, decided to run orientation itself. The result was a bungled mess. Salient (3 March 1992), the VUWSA newspaper, described the Executive as still arguing about which acts should be scheduled ten days before the programme was due to start. Such disorientation left little time to give advance publicity to the programme, resulting in poor attendances and no doubt large financial losses.

Such shortcomings, could lead to a shakier future for student entertainment on certain campuses now that the NZSAC's support is to disappear. The dissolution announcement came as a total surprise to most students. Apart from a few committee members and student politicians privy to the workings of the NZSAC few students were told in advance of what was going on and no general attempt was made to solicit the opinions of students nationally through referenda or student council meetings.

The NZSAC's closure is an issue which deserved public debate. The savings campuses will make in not having to pay their levies - the AUSA for example contributes around $24,000 annually - have to be balanced against the problems smaller and less organised students' associations will have in individually attracting acts to their campuses. Other big questions include how national orientation tours will be organised with no central booking agent, and who will fund and organise national student radio and newspaper training workshops. Better organised students' associations will largely be able to do without the NZSAC, but even they might find they have taken on more than they bargained for in these areas.

Originally published in The New Zealand Monthly Review July/August 1992 pp.8-9.

© Wayne Stuart McCallum 1992.

NZUSA at the Crossroads in the 1990s

An anti-National Government rally in Christchurch Square in 1991.

The NZUSA's local members were notably absent.

W.S. McCallum

Since the election of the National Government in October 1990, the New Zealand University Students' Association (NZUSA) has faced a series of major challenges to its narrow platform as a tertiary education lobby group.

Perhaps its most interesting of these challenges has come from within its own ranks. Since 1986, when the NZUSA decided to shed its interest in a broad range of national and international issues, the organisation has been noticeably uninterested in matters such as international student rights. A Canterbury University student, Nadia el Maaroufi, decided to try and push the NZUSA out of its disinterest in 1991. In July she presented a motion to the Student Representative Council (SRC) of the University of Canterbury Students' Association (UCSA). It read "That the SRC endorses that the NZUSA uphold the indivisibility of Chapter 9, article 55, subclause (a) to (c) of the United Nations Charter, that education is a fundamental right for all without discrimination to race, sex, language, colour, religion or political affiliation, as policy and that the NZUSA enact this as policy through the appropriate international student organisations and fora."

Having gained NZUSA support, Ms el Maaroufi had her submission passed on to the NZUSA August 1991 conference. During debate, Charlotte Denny, the NZUSA President, outlined why the NZUSA should ignore the submission. She opposed the submission on the grounds that NZ education issues were the NZUSA's major concern, and stated her belief that it was inappropriate for the NZUSA to spend time on international human rights issues. Despite her recapitulation of this much-repeated NZUSA argument, a motion put to discuss the submission further at the NZUSA's Workshops in February 1992 was passed by 28 votes to 21. Although the motion's supporters (Canterbury, Auckland and Otago) were slightly outnumbered by four students' associations (Waikato, Massey, Victoria and Lincoln), the three have more votes due to their larger student populations.

That the submission got so far was surprising, particularly given the UCSA's indifference and opposition to expressing opinions on international matters of conscience over the last two years. A motion to the UCSA SRC in 1990, asking that the UCSA support the Mark Curtis Defence Committee, was lost. The UCSA President in 1991 both publicly and privately stated his opposition to such motions. It is fortunate that, in this case, the UCSA decided to show its support.

Charlotte Denny's opposition to the NZUSA expressing support for the UN Charter was paradoxical when examined alongside the NZUSA's own campaign to force the New Zealand Government to support article 13 (12)(c) of the International Covenant on Human. Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The article states "Higher education should be made equally accessible to all ... in particular by the progressive introduction of free education". In August 1990, the NZUSA declared that it would fight a court action against the Government on the grounds that the introduction of higher tertiary fees violated New Zealand's signature of the Covenant. The difference here was that the NZUSA was pragmatically exploiting an international agreement to further its own education policies. Ms el Maaroufi's submission had no such role in the NZUSA's education agenda.

NZUSA confidence in the legal action was misplaced. A year after pinning its hopes on the action, Charlotte Denny announced to the NZUSA August 1991 conference that it had been abandoned. Having spent an undisclosed amount on the court action (the Wellington student newspaper Salient estimated the figure at "several thousand dollars" - 17 June 1991), the NZUSA was forced to discard it because National's new Study Right scheme devolved the setting of tertiary fees to individual universities. Under Study Right, the Government was no longer directly responsible for the setting of fees and couldn't be prosecuted in court.

Other major challenges to the NZUSA's leaders have been the National Government's social welfare cuts and its introduction of the Employment Contracts Act. Both of these measures directly affected students. Tertiary students depend heavily on part-time jobs to supplement the inadequate term-time income offered by student allowances (at least for the lucky few who qualify). The reduction in the dole was a blow to students unable to find holiday jobs so they could raise funds for another year's education. As for those lucky enough to find work, the Employment Contracts Act fails to specify a minimum wage for teenage workers. Student Job Search Canterbury was alarmed at the tendency of prospective employers to request under 20 year-olds, with the aim of paying them less than the minimum wage (Christchurch Star 14 September 1991).

The NZUSA's reaction to these developments was one of mild opposition. In May 1991, the NZUSA publicly called on the Government to raise taxes for higher income earners, rather than cutting welfare, and in particular education expenditure (Evening Post 7 May 1991). It also declared its opposition to the Employment Contracts Act's lack of protection for workers under the age of 20 (Christchurch Star 2 May 1991).

Evidence of active NZUSA opposition to broader National Government policies was, however, difficult to find. The NZUSA largely maintained its role as a tertiary education lobby group, isolated from broader opposition to the National Government. The one exception was the NZUSA's co-operation in a National Week of Action with other education and health groups form 17-24 July 1991. Otherwise, the NZUSA was absent from various nationwide and local demonstrations of broad opposition to Government policies. The NZUSA did not support a protest at Parliament on 15 March 1991 against benefit cuts and the Contracts Bill. It did not support the Council of Trade Union (CTU) nation-wide day of action against the Contracts Bill on 30 April 1991. Neither was it present at the October Coalition's nationwide protests on 24 October 1991. And, unlike the Association of University Staff (AUS), the NZUSA did not offer practical opposition to employers taking advantage of the Employment Contracts Act. Earlier in 1991, the AUS recommended that its members boycott Whitcoulls for its failure to recognise its employees' chosen bargaining agent. Later in 1991, the AUS called for its members to boycott Air New Zealand for its treatment of its workers.

On the issue of tertiary education, the NZUSA remained active in 1991, but with mixed results. The court case failure has already ben mentioned. Of three national days of protest in 1991, two were confined to campus rallies (17 April and 18 September), with stunts such as auctioning off buildings and lecturers, and letter writing campaigns. Such activities do not have a very high public profile. The nationwide NZUSA marches on 17 July 1991 did, but there were notably poor turnouts in Auckland and Christchurch. The Waikato Students Association (WSU) failed to organise a march at all. The WSU President, Simon Scott, vetoed the march, and opposed it on the grounds that marches were "for losers"(Nexus 14 August 1991). In August 1991 WSU members sacked Simon Scott, disgruntled at his lack of interest in education issues as well as accusing him of poor administration. Diana Brett, Scott's replacement as President, wrote to the author in August 1991, saying Scott's lack of support for education issues was the primary cause of dismissal. She expressed WSU's hope of renewing its education activism.

The NZUSA, from 1990, widely criticised the National Government's inability to fund universities to the level necessary to cope with growing student rolls, but its lobbying was ineffectual in stopping the spread of limited entry criteria for stage one courses, university overcrowding, the removal of hardship funds, and the introduction of means testing for student allowances. The NZUSA's primary goal "To insure the standard tuition fee is removed for 1992 and not other significant fees are imposed by universities of the Government" (Salient 8 April 1992) has not been achieved. The devolution of the setting of fees to individual universities has merely replaced one set of fees with other sets, which vary in price depending on the university you study at. By the 1990s, educational activism by the NZUSA had been reduced to the ineffective lobbying of its various constituent associations of their University Councils, in a vain series of attempts to reduce fees whose rise upwards has become an annual event.