Venetic Home Page Writing Venetic@MySpace

VENETIC'S VIEW

ARCHIVE

by W.S. McCallum © 2004, 2005

E. Banwell

Venetic’s View - The Return from Coventry

Life tends to be an ongoing mural with bits constantly being roughly sketched out and then painted on in greater relief and detail, so in the interest of keeping things up to date, below is the reply I received on 15 March 2005 from Stephen McCarthy (printed here with his assent) about my feelings of neglect regarding the “Venetic’s View” column on the bands.co.nz site. It seems that sometimes it does pay to think aloud and clear the air rather than adopting that very Kiwi approach of sullen silence that all too often leads to long-term misunderstandings…

"Hey i just read your bit on your site about me giving you the cold shoulder..... just misscommunication my friend and being real busy. Sorry I didn't catch up with you when you were down... it wasn't intentional and sorry i didn't email you back. I work full time at an advertising agency, run a website, in 2 bands and try to keep my wife happy at the same time so sometime these things just slip through the net. The article you wrote on AZ was some of the best writing i've ever had on the site and i think it's great it ruffled feathers, i even got wind from amplifier.co.nz that it did indeed cause quite a stir.... which i think is great!!!"

Stephen

The Old Christchurch Cold Shoulder

or

Venetic’s View Comes To An End

The piece below dated 11 January 2005 was the last article I wrote for the bands.co.nz site and it was not published on the Christchurch-based independent NZ music Web site.

I never did find out specifically why it was not published, as Stephen McCarthy, the site's administrator, never saw fit to tell me. As it came a few weeks after the ruffled feathers my Ahmed Zaoui article (see below) caused among various Old Boys on the NZ music scene, and a couple of weeks after Mr McCarthy avoided meeting me while I was in the Garden City just before Christmas 2004, I will assume this particular article was what precipitated my being made persona non grata on this particular site.

This is however just my speculation, and you can draw your own conclusions.

This sort of thing is what I call "The Old Christchurch Cold Shoulder" or, in normal parlance, being sent to Coventry. It is a pattern of behaviour I have experienced before, having grown up in Christchurch, and is something I have come to associate with that very English of city's cold way of going about things: don't stir things up, maintain appearances at all costs, and for heaven's sake avoid a scene.

So Long and Thanks for All the Records

11 January 2005

There were rumours about the impending sale of Echo Music some time before it was officially announced on 20 September 2004. The takeover by Auckland-based Real Groovy of the largest privately-owned recorded music retailer in the South Island marked the second stage of its nation-wide expansion. The first stage had occurred in Wellington a few years back, when Real Groovy opened its Cuba Street premises just a couple of blocks away from Slow Boat Records. Happily, Slow Boat withstood this development and is still with us.

Echo Music’s decision to sell up gave Real Groovy both the benefit of its long-standing Christchurch and Dunedin retail outlets, and placed it in the position of having stores in all four major centres in New Zealand for the first time.

I was in Christchurch a couple of weeks ago and decided to have a mosey around to see what the lay of the land was as a result of this sale. My first stop was the Echo Music store in High Street, which was empty apart from various boxes and odds and ends still scattered around inside. There was a sign on the door directing customers to the new Real Groovy store just a couple of streets away, so I strolled over to have a look.

It was in a curious location - just across the road from an old cinema which is now a gathering place for holy rollers and their disciples. This new retail outlet’s proximity to God contrasts somewhat with the location of Real Groovy’s Wellington premises - a section of Cuba Street where, long after closing time, streetwalkers ply their trade.

A cursory survey showed the new Christchurch premises to be structured along the same lines as Real Groovy’s Wellington store. Not being particularly flush with cash that day, I had a browse through the cheapo vinyl bins and, having found a few LPs, I took them up to the counter.

I was served by one of the two people among the crew on duty who I recognised from the old days of Echo Records, back before they changed their name to Echo Music. Once I had handed him the LPs and placed my Real Groovy card on the counter, the conversation went like this:

Ex Echo Records Person: (Having carefully scrutinised the LPs and failed to spot any prices, followed by an unsuccessful search through his bar code sheet…) “They’re sale LPs - do you know how much they are?”

Venetic: (Who was tempted to say “20 cents”…) “I don’t know, but in your Wellington store the sale LPs are $3 each.”

EERP: (Looking dubious, he casts around for one of his better-informed new colleagues, who tells him they are $5.) “They’re $5. Is that OK?”

Venetic: (Pausing reluctantly because he’s a tightwad, but desperately wanting to hear Dino Desi & Billy’s rendition of “Hang On Sloopy” and eagerly anticipating his glee at hearing Cher murdering 60s classics like “Sitting on The Dock of The Bay” with a full Muscle Shoals backing band on an LP she recorded in 1969…) “Yeah, OK.”

EERP: (Searching for the appropriate bar code) “Ah, there it is!” (Begins laboriously scanning and entering the bar codes into the computer.)

Venetic: (Knowing full well he hasn’t but asking anyway:) “Did you scan my Real Groovy card?”

EERP: (Halts the laborious process he has nearly completed by now and looks nonplussed at the card. Adopts the stern reproving tone an adult uses on a toddler who is not toilet-trained and who has just done a wee-wee) “Just so you know for next time - you’re supposed to present your card BEFORE anything else is entered.”

Venetic: (Who has had a Real Groovy card for some years now and has been using them longer than this guy) “It was there on the counter all along! You just weren’t looking.”

EERP: (Scans the card and peers at an aberrant result on-screen) “Are you from Christchurch?”

Venetic: (Who is in fact from Christchurch but not wanting to confuse the guy) “It’s a Wellington card.”

EERP: (Pressing buttons to tweak the system) “I’ll have to do a special entry since you’re not on the Christchurch system…”

As he was fiddling about, my mind went back over all the years I had been buying stuff off Echo Records. Back to the early 1980s. Memories of mullet haircuts behind the counter in Echo’s original New Regent Street store, and the easy-to-operate till they had back in those days. Memories of finding mint-condition copies of classic soul and funk LPs by the likes of Curtis Mayfield, Archie Bell & The Drells and Sam & Dave in the bargain bins for $2 because in the days of 80s stadium rawk they were no longer considered particularly worthy. Recollections flooded back about other remarkable music I had discovered in that little store - the Ray Charles Atlantic boxed set, Underground by the Electric Prunes, The Modern Lovers, those Yes albums… (OK, stop your groaning - when you’re 14 you’re allowed to have the occasional appalling lapse of musical taste).

Then I smiled at the thought that, over all those years, in sharp contrast to the large quantities of vinyl I had purchased off them, I had only ever bought a single CD from Echo Records.

So long Echo, and thanks for all the great LPs.

The Ultimate Career Move

21 December 2004

Three dead singer-songwriters - buy their products at a store near you...

It’s during this supposedly festive season that mindsets turn to very negative thoughts. It may be due to the relentless commercialism of Christmas, a time of year when the ringing of cash registers has more importance than any religious observances among what is now a largely non church-going nation. (When was the last time you went to Mass on Christmas?) It could also be due to the excess intake of alcohol and other drugs that occurs as we wish the old year good-bye and welcome the new one in. (I won’t bother asking about the last time you were on drugs and frankly I don’t want to know.) Or it may have something to do with the stress and bullshit involved in having to spend time in extended close contact with unpleasant relatives. Perhaps it is just the nagging insistence of that social demand that we all be HAPPY HAPPY HAPPY. A social demand that reaches its extreme on New Year’s Eve, when total strangers approach you in the street and look like they’ll beat the crap out of you if you don’t wish them a happy New Year with sufficient exuberance. On a more philosophical level, this is the season when a good many people take stock of all the New Year’s resolutions they made twelve months ago and failed to fulfil and get profoundly depressed. Or maybe it’s something as shallow as the trauma involved in the pretence of being nice to each other for a few days to make up for having been bastards for the rest of the year. Whatever the reason, a good many people start thinking negative thoughts, along the lines of: “what’s it all about?”, “what’s the point?” and “why am I bothering?” And a good many start pondering suicide.

I have been thinking about suicide recently. Not my own, I hasten to add (sorry to disappoint any Ahmed Zaoui supporters out there), but rather the concept of suicide as it affects musicians, and particularly singer-songwriters.

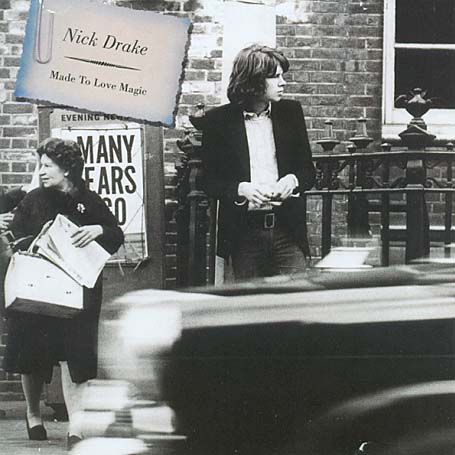

In addition to watching the onset of the festive season, over the last several weeks I have noticed certain album releases that inexorably brought me back to the subject. The first was a compilation of material by Nick Drake which was prominently displayed in a certain CD store in Palmerston North in September. It included a few previously unreleased “lost” tracks as a pretext for getting fans of the early 70s English singer-songwriter to buy a bunch of old songs they doubtless already have. I even considered buying it but, not wanting to be a pawn of the industry corporate that had placed it on the market, I decided I could do without these “lost” treasures. Then, in ensuing weeks and months, I spotted expensive vinyl reissues of Nick Drake’s three original LPs in shops as far apart as Paris, Geneva and Wellington.

This was no coincidence of course, just signs of the music industry’s love of anniversaries for the pretexts they offer to repackage old goods and flog ‘em off in new shapes and formats. “It was twenty years ago today”, so we’ll hype Sergeant Pepper’s and sell a few more million copies (that was back in 1987). Or, it’s 25 years since Elvis died so we’ll release… [add your own list here]. (That was in 2002.) Hey, it’s been 25 years since the Clash released London Calling, so we’ll release a deluxe extended version! (2004)

Getting back to Nick Drake, 25 November 2004 was the thirtieth anniversary of his suicide. Hence the accompanying re-release of his LPs on nice thick vinyl for the collectors, the release of two fairly redundant compilations (the one I mentioned, and another one that just features tracks off the aforementioned original three LPs), and probably other releases providing variations on his short oeuvre that I haven’t noticed because I’m not so obsessed by it that I have the inclination to track them down.

Poor old Nick Drake. His three original LPs were released on Island Records from 1969 to 1972, during the golden age of singer-songwriters. He had people like John Cale and Richard Thompson play on his recordings, and in Joe Boyd he had a heavy-weight producer with a big reputation in the folk field. Yet while, for better or worse, people like Melanie, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, Laura Nyro, Carole King, Neil Young and even Neil Diamond experienced peak sales, critical success and popular acclaim in those years, Nick Drake was largely ignored. Disillusioned by the commercial demands of the music industry, crippled by his own shyness, and hamstringed by his refusal to tour, he was only part-way through recording a fourth LP when he overdosed on anti-depressants. The sad irony is that since his death he has enjoyed far greater renown than he did during his lifetime. His original three albums, which did not shift many units during his lifetime, were reissued as a boxed set in the mid-1980s, have become treasured items and are now starting to exchange hands for ridiculous prices. A pink Island label pressing of his first LP, Five Leaves Left, was sold on E-bay in September for the equivalent of $NZ 1,755. Drake’s fans show a cult-like devotion to someone who they have turned into an almost mystical figure. They treasure his innocence, his sensitivity, and his undoubted artistic merit, even if his second album, Bryter Layter, sounds overproduced to my ears. Thirty years after his death, more people care about him and his music than they did when he was alive.

Maybe it’s just me, but I see this development, which is not an isolated trend, as a very sad comment on human nature.

Two other singer-songwriters from back in Nick Drake’s day come to mind who experienced similarly grim endings at fairly young ages. They too have subsequently been recycled by the music industry and reintegrated into its pantheon. One is Phil Ochs, who committed suicide by hanging, and the other is Tim Buckley, who died of a drug overdose. In terms of the music industry’s accepted canon of celebrities they are ranked a bit higher up the ladder than Drake, having had longer careers and a degree of international success that he never enjoyed during his lifetime. Phil Ochs, who started out as a protest singer in the early sixties, was once spoken of with the same sort of respect that people reserved for Bob Dylan, and was regarded as such a threat by the US Government that he was placed under continual surveillance. Reportedly he has the dubious honour of being the rock performer with the largest file ever compiled by the FBI. Tim Buckley was less earthbound in his concerns, merging jazz and free-form influences into his music in the late 1960s that challenged boundaries rather than conforming with them. Both experienced a decline in fortunes in the 1970s, when musical tastes changed and they found themselves on the wrong side of a new generation gap that left their music looking outdated.

Now, three decades later, their back catalogues are being re-released on vinyl and CD, and even previously unreleased concert performances by them are being released and greeted with respectful reviews and solid sales. Instead of being considered a has-been, nowadays rock critics use words like “visionary” and “timeless” to describe Tim Buckley and his music. As if to add stature to the misty tragic nature of his legend, he had a talented singer-songwriter son who also died a tragic death by drowning. And Phil Ochs, who seemed totally irrelevant at the time of his death in 1976, now seems more relevant than ever. The earnest musical campaigning against Bush this year could have benefited greatly from some anti-war vitriol from Phil Ochs.

Yet, had Drake, Ochs and Buckley (or even his son) survived into old age, would they be regarded with such reverence these days? My guess is that they probably wouldn’t have been. They would still have found favour with a smaller circle of devotees, but it’s their tragic demises that lend them that extra mystique.

By way of an illustration of this phenomenon, consider Janis, Jimi and Jim, the ultimate triumvirate of 60s rock stars who lived fast and died young. If Janis Joplin were still alive today, would she be held in the same reverence? Would Jimi Hendrix be considered anything more than a noodling old fusion guitarist, out of touch with modern trends in black music? And would the thought of Jim Morrison at the age of 60 turn his fans on as much as those photos of him in his twenties in those tight leather pants? Probably not. Yet with them dead, the corporate product repackaging possibilities are endless. If you own a bootleg of Hendrix farting in the Marquee’s toilet in 1968 you could release it as a commercial item these days, and such is the plethora of recycled official Doors material out there that it defies imagination.

It is very sad to say so, but in the cynical world of the music industry, a young death is definitely a major selling point.

The latest case in point is Elliott Smith, who stabbed himself to death in October 2003, aged 34. Like his singer-songwriter forebear Nick Drake, he was plagued with self-doubt, yet had already garnered a following and some trappings of success that Nick Drake never achieved (and possibly never aspired to - would Nick Drake have played at the Oscars for instance?). Already the material Elliott Smith was working on at the time of his death is out in the shops. Reviews of it are steeped in references to tragedy, a hushed respect for his death that was… SO ROCK ’N’ ROLL, y’know? The industry’s machine is at work, building up the legend, paving the way for future years, probably future decades, during which we will be drip-fed “lost” material “rediscovered” from the vaults that will sustain the legend, possibly even mounting up to the forbidding heights of the monument erected to Jim Morrison or, at the very least, to the modest scale of the one erected to Nick Drake.

It’s a sick sick world.

Merry Christmas!

The Great CD Scam

5 December 2004

W.S. McCallum

Even the most mundane event can point to an enormous change that has come to be taken for granted. I experienced one such incident when I was in a record store in Lower Hutt a couple of years ago. It was a Saturday, the sort of day when parents drop by with their kids while they are doing the weekly shopping. A man in his thirties came in with his little daughter, who looked about four years old.

While dad browsed through the racks, his daughter had a little wander, stopping to stare at a strange contraption beside the counter that she had never seen before.

“What’s that daddy?”

“It’s a record player.”

“What’s it for?”

“You play records on it.”

“What’s a record?”

“It’s what they had before CDs came along.”

It was a bit over twenty years ago that the first rumblings of a mighty change in the world of recorded music were first felt. Reports started coming through concerning a new-fangled thing called the “compact disk”, or “CD” as it soon came to be called. These reports stated in no uncertain terms that CDs were going to revolutionise music as we knew it. Journalists unquestioningly cited audio technology experts, recording company and audio equipment PR men and various other such learned sources stating that CDs would offer music lovers higher fidelity than LPs ever could. CDs would last forever and were practically indestructible - they didn’t buckle and scratch like records. CDs were the ultimate in audio technology. CDs were THE FUTURE.

It’s funny how history can prove certain supposedly self-evident truths to be so irrevocably and undeniably wrong that subsequent generations come to wonder how anyone could be so dumb as to have believed them. Examples of such truisms include the tenet (believed for millennia) that the Earth is the centre of the Universe, or that human slavery is “natural”, women are inferior to men, religion brings peace to mankind, nuclear power is safe, or that Communism or the market economy can provide the path to Nirvana, just to name a few. As was the case with these falsehoods, the credo that the CD was the answer to our music-listening prayers has come to be proven oh so very wrong. And it only took about twenty years for this to become evident.

Not convinced are you? Still clinging to your cherished collection of silvery tacky plastic? Hanging on to those hit CDs by Dire Straits and other classics from the 1980s in the hope that they’ll provide a retirement nest-egg for you or your children? Well, in that case, you have the following storage issues to come to grips with:

1. CDs can’t handle sunlight. It breaks down their chemicals, thereby destroying the recorded medium embedded in their plastic. Not to mention the fact that it can buckle them. Even their poor-quality paper covers fade easily in sunlight.

2. CDs are brittle and break quite easily. In fact they are almost as brittle as 78s. Even bending them can damage the recorded medium inside them. As such, they actually constitute a retrograde step compared with the resilience of vinyl LPs and 45s.

3. CDs scratch easily. Even gently wiping the wrong sort of fabric across them will leave marks, let alone the sort of wear and tear most people subject them to. Hence the booming trade in hi-tech CD surface repair products that has arisen in the last couple of years. One of the selling points for CDs back in the 1980s was that you would never have to worry about scratched recordings ever again. Tell that to some mother whose cherished Billy Joel CD skips all over the place in her CD player because the family toddler found out it makes a great little Frisbee…

4. CD rot. As if the preceding three points weren’t bad enough, in recent years there have been reports of a mysterious phenomenon popularly known as “CD rot”. This is what happens when the data medium inside your CDs becomes pitted and corroded. Over time, this medium deteriorates to the point where the CDs become unplayable. The CD manufacturers blame this on poor storage of the CDs by their owners in damp or excessively hot conditions (and this after having had the nerve to tell consumers for all those years that CDs were practically “indestructible”…). The sad truth of the matter is that research and practical experience are now showing that CDs last about 15 to 20 years on average before they start deteriorating naturally at various rates due to shortcomings inherent in the materials from which they are manufactured. By comparison, simulated ageing tests in laboratories have shown that newer technology such as good-quality CD-Rs should last 200 to 300 years if handled and stored properly. Little wonder that the recording industry hates the booming trade in CD burning equipment. Not only is a home-burnt CD-R a cheap, efficient storage medium, it also lasts longer than the traditional CDs you buy in stores.

As if to highlight the fact that it lied to us about the CD’s invincibility back in the 1980s, over recent years the recording industry has unsuccessfully attempted to replace CDs with newer technology: first came DVD audio disks, then SACDs, and now there is a hybrid CD/SACD/DVD product that can apparently be played on practically anything except a phonogram. Apart from certain audiophiles who have money to burn, these products have not been particularly popular with the general public. Their higher retail prices have a lot to do with this. By way of an explanation, the recording companies offer up the logic that higher audio quality = a higher cost price per unit, which is why the consumer has to pay a higher retail price.

There is nothing new about this argument - the same one was offered to the public as justification for CDs costing substantially more than LPs when they first came out in the 1980s. The truth of course is that initially, during the product development stage, unit costs were undoubtedly higher for CDs. But then, once the manufacturing technology had been mastered, although production costs dropped remarkably, $30+ retail prices were maintained because the music industry, from manufacturers through to retailers, was only too happy to keep enjoying the benefits of inflated profit margins. Prices vary from country to country, but generally speaking, audio CDs themselves nowadays cost less than a couple of dollars to make. On top of which, because CDs are more compact and lighter than the LPs they came to replace, manufacturers and wholesalers also made substantial savings on storage and shipping costs, while retailers found they could stock a lot more units in the same amount of shelf space. A real win/win situation all round, with consumers being the only ones who lost out. Consequently it is not surprising that the general public did not buy into the recording industry’s hi-tech high-cost replacements for the supposedly invincible CD, and this time around history did not repeat itself.

In spite of their attempts at pushing the new audio disk formats, and belatedly slashing retail prices for CDs in the face of rampant illegal and unstoppable home copying, the majors have been unable to forestall a major downward spiral in global CD sales. To make things worse for them, their efforts at stopping home CD burning and private copying of CDs to newer formats such as MP3 by prosecuting private individuals and firms like Napster have not only failed to stem the tide, they have also resulted in increased consumer alienation.

The final surrender came in September 2004, when Sony announced it would finally be releasing Walkman products capable of reading MP3 files. In terms of the audio CD’s decline, this decision marked a defeat comparable to Sony’s forced abandonment of the Betamax video format in favour of VHS for the home consumer market 20 years earlier.

Like the earlier popularity of home copying of VHS video cassettes and audio cassettes, through its widespread support for use of MP3s, the general public has shown it doesn’t really care that much about quality or copyright, so long as it can get the product it wants in a usable format that is cheap. This consumer preference has diddled Sony and its rival corporates out of potential profits (made ostensibly in the name of product quality) that would have been astronomical.

Cut-price CD retailers like the Warehouse and the CD chain stores are one response to this groundswell consumer preference. Another response is the new on-line “record stores” that are popping up as an attempt to claw back some money via legal music downloading, but only time will tell if they succeed.

To put it bluntly - nowadays CDs just don’t cut it - they are a tacky, poor-quality, obsolescent, overpriced format that people are not prepared to shell out $30 to $45 for anymore. Particularly not the youth market - these days even teenagers from affluent families are getting their music through free file-swapping rather than going out and buying it from a store, and they are doing so to a far greater extent than the home cassette copying that the music industry got so worked up over in the 1980s.

So where does this leave us - the music makers? Paradoxically in a position of both great strength and great weakness.

Great strength in the sense that the dissemination of MP3s offers a contemporary form of “word of mouth” that previous generations of musicians could only dream about. Interested listeners from here to Timbuktu can easily download Kiwi music via the Internet and can hear bands they might otherwise never have even heard of. Back in the early days of NZ rock’n’roll, what would people like Johnny Devlin or Ray Columbus & The Invaders have been able to achieve internationally if they had received such exposure?

But it is also a position of great weakness in that, given how widespread MP3 file use is, the value of recorded music as a merchantable product has now declined to an all-time low. No matter how small the pittances in royalties from CD sales received by groups signed to recording companies, these sums look enormous compared to getting nothing at all from those free MP3s being swapped left right and centre out in the ether.

Whatever the final outcome of these momentous changes, I can foresee a day in the not-too-distant future. The scene is an antique store where, whilst hunting for a vintage Lord of The Rings figurine to fill a gap in his prized collection, a middle-aged father will get distracted when his four year-old girl, seeing a strange contraption on the counter, stops him and asks:

“What’s that daddy?”

“It’s a CD player.”

“What’s it for?”

“You play CDs in it.”

“What’s a CD?”

What this sad CD boy needs is a collection of good vinyl....

Musical Babes in the Political Woods

21 November 2004

At approximately 11.30am on 29 September 1994, Cheb Hasni, a 26 year-old Algerian singer, was stopped in the street not far from his home in the neighbourhood of Gambetta, in Oran. According to his brother, who witnessed the incident, a stranger greeted Hasni warmly, acting as if he were a fan. Having approached Hasni and placed his arm over his shoulder, he then unexpectedly pulled out a sawn-off shotgun and fired at point-blank range at Hasni’s neck, followed by a second gunshot to the head to finish him off, upon which he made a quick getaway in a car parked nearby.

Although Algeria was a country that had experienced increasingly violent turmoil since the abortive elections of 1991-2, Cheb Hasni’s murder ten years ago came as a particular shock at that time to the country’s youth. While he had initially made a name for himself in 1987 with a song called “Baraka M’ranika” that was considered licentious and shocking by the country’s religious extremists, his later career was devoted to lyrics of a romantic inclination and he had a reputation as being more than a bit of a crooner, his preferred topics being sexual politics and love. Nevertheless, it was generally assumed that his murderer (who was never caught) was an exponent of Algeria’s Islamic religious fundamentalist movement that, having failed to win power through the ballot box in 1992 after being stymied by the manoeuvring of the Algerian government and military, was now attempting to gain it by force.

Along with journalists, writers, academics, foreigners, and anyone who these Algerian advocates of a restrictive interpretation of Islam might take issue with and target for kidnapping or assassination, Rai musicians were prominent among their victims.

Rai is not a genre that features on the musical map in this part of the world, so some brief background is warranted. Rai, (or ‘Raï’ as it is transcribed in French) is a word that means “opinion”. It is a good name for an outspoken style of music that, in strange parallel to punk rock, was born in Algeria in the late 1970s and immediately raised the hackles of both Islamic fundamentalists and government officials for its opposition to traditional values, its anti-authoritarianism, and its libertine approach to life.

Yet let’s be clear over what we are talking about here: Rai advocates the sort of values that most people in Western countries take for granted. Take, for instance, the songs of Cheb Khaled, who has been called “The King of Rai”. In them, as well as calling for religious and cultural tolerance, he voices support for women’s liberation. While New Zealand feminists may use the phrase “barefoot and pregnant” laughingly or disparagingly in reference to the values of Aotearoa’s crumbling patriarchal society, few if any of them have any personal experience of the level of servitude involved in being an Algerian woman living in an arranged marriage, confined to home by a jealous, possessive spouse whose values make your average Kiwi redneck look like a pinko liberal. Within this very traditional social context, singing about women’s lib is not something that goes down too well with the FIS (Islamic Salvation Front), the main political party that spearheaded the Islamic fundamentalist movement in Algeria.

Nor did these people, with their push for a return to traditional values and classic Arabic culture (a controversial stance in a country with a large non-Arab indigenous Berber minority), view Khaled’s changing musical style very positively in the 1990s. Working as an exile in Paris, he recorded with big-name producers like Don Was and Steve Hillage, and began incorporating jazz, hip hop and reggae into his sound. Islamic fundamentalists tend to see this sort of thing as indicative of cross-cultural bastardisation and Western decadence. Even something as basic as a choice of producer can be held against you if you’re a Rai musician. In 1996, Khaled had to fend off criticisms of his hit single “Aicha”, which went to number one in the French charts. His sin? It had been produced by Jean-Jacques Goldman, who is not only a star performer in France, but also happens to be a Jew. Such a choice was like a red rag to the bull for Algerian Islamic fundamentalists.

Khaled is one of the success stories of Algerian music, but others have not been so lucky. Various Algerian musicians have fallen victim to the wave of religious intolerance that has traversed Algeria with the advent of the FIS, and has still not subsided.

Rachid Baba Ahmed, a prominent Rai producer, who made his name by introducing electronic instruments and the latest studio technology to the genre was, like Cheb Hasni, also murdered by Islamic fundamentalists in late 1994. On 12 August 1995, the Kabylian (Berber) chanteuse Lila Amara and her husband were murdered at Tixeraïne. During the night of 18-19 September 1996, Cheb Aziz, another Rai performer, was abducted in Constantine, presumably by Islamic fundamentalists. His body was found on 20 September 1996. Also worthy of note is the murder of Lounès Matoub, a Kabylian singer and poet, who was riddled with bullets when stopped at a fake roadblock on 26 June 1998 in Tizi-Ouzou. In his case, as is common in Algeria, no one claimed responsibility, but it was assumed that the GIA (the “Islamic Armed Group” - a bunch of gun-toting religious acolytes founded in Algeria in 1989, and which received an influx of disaffected members from the FIS in 1994) was behind his murder, because Matoub had been a vehement opponent of Islamic fundamentalism, as well as having enemies in the Algerian government (he was banned from State TV and radio in Algeria and his concerts were prohibited).

By now, there will be various readers out there in Webland, heads spinning from all the exotic names, places and abbreviations (FIS, GIA…), who are wondering what all this has to do with New Zealand music…. Well, this brings me to a musical event held in Auckland on 21 November 2004: the Ahmed Zaoui Benefit Concert, which brought together Kiwi performers such as Chris Knox, Don McGlashan, Dave Dobbyn and the Brunettes. That Sunday night, they performed songs to raise funds for the release of the aforementioned Mr Zaoui, who has been in many a headline since he was detained (indefinitely so it seems) for entering New Zealand on a false passport in December 2002.

To provide some brief background; Zaoui was a member of the FIS’s Consultative Committee, and was elected as an FIS parliamentarian for Cheraga in the first round of the Algerian elections in December 1991. However, following this round, and faced with a likely FIS victory, the Algerian government maintained power simply by discontinuing the elections. In 1992, Zaoui, who consequently never had the chance to occupy his seat in parliament, went into exile, becoming the chairman of the FIS’s Co-ordinating Committee abroad, as well as having an Algerian government death sentence placed on him for his opposition activities.

Zaoui is also persona non grata in France, Belgium and Switzerland. To cut a long story short, he was given suspended sentences for "associating with criminals" - namely smuggling forged documents and weapons to somewhat-less-than-pacifist groups in Algeria while he was in France (in 1993) and in Belgium (in 1995). In Switzerland, which he entered illegally, he was also hauled in for questioning in May 1998 in relation to a network that was smuggling arms and false documents. There, he was detained only for so long as it took the Swiss to get rid of him. They discovering that (surprise surprise) neither the French nor the Belgians wanted Zaoui back, even though he had skipped both of those countries, most recently having escaped from the loose form of home detention he had been placed under in Belgium. The Swiss authorities placed him under much tighter house arrest, depriving him of his fax, phone, computer, etc, and kept him under close guard until they passed a specific law so they could deport him as a threat to national security. On 30 October 1998 he was deported to Burkina-Faso, the only country that would have him, in exchange for an undisclosed sum of money. As it turned out, Zaoui decided not to hang around, and skipped Burkina-Faso too, finally ending up in Auckland.

All of which leads me to wonder the following: If the musicians and performers at the Ahmed Zaoui Benefit Concert had grown up in Algeria instead of New Zealand, would they be so keen on supporting a figurehead from a part of the Algerian religious and political spectrum that is profoundly at odds with long-standing rock’n’roll values such as anti-authoritarianism, a libertine approach to life, and the questioning of tradition and conservatism?

In 1985, as Left Right & Centre, Chris Knox and Don McGlashan recorded a single calling for the halting of a New Zealand rugby tour to apartheid South Africa - a profoundly unjust, racist regime. This time around, the issue is not so black and white. However well-meaning they may be, it seems that these musicians have pinned their banner to the wrong cause. My sympathies lie instead with the Algerian musicians who have had to live in fear and/or in exile as a result of the religious fundamentalism of the likes of Mr Zaoui and his colleagues, rivals and enemies within the Algerian Islamicist movement.

Some People Who Work in Record Shops

7 November 2004

W.S. McCallum

Anyone with any interest in music invariably ends up spending time in record shops (or “CD stores” if you prefer more with-it terminology). While most of the staff who work in these places are happy, well-adjusted people with a firm grip on reality, a disturbingly large number of them seem to suffer from various strands of a peculiar form of psychosis that comes from being shut away indoors day after day, completely surrounded by their wall-to-wall merchandise. A few case studies are provided below for your delectation.

1. The Ageing Baby Boomer. This is a guy (they’re invariably male) who came of age in the 1960s and 70s and subconsciously believes that modern music ended its development around the time of the brief rise and fall of the first wave of punk rock. The Ageing Baby Boomer (or “ABB” as I like to call them - just one letter shy of “Abba”) will begrudgingly give a nod of approval to the likes of the Datsuns, but steadfastly holds that they are nowhere near as good as Deep Purple or Uriah Heap. His main criticism of under-25s is that they’re too young and ill-informed to know what good music really is. The ABB frequently has a well-developed beer gut, and often wears his hair in a carefully-tended ponytail in an effort to hide his receding hairline. As a middle-aged businessman, he shows a level of concern for profit margins that is far removed from the communal values and caring and sharing he advocated in his younger days as a hippy.

2. The Youth Supremacist. This denizen of record stores is at his (yep, they’re invariably males) most virulent stage under the age of 22. His certainty that the “kids” know where it’s at, buoyed along by a music industry that pushes mass-marketing specifically targeting his age group, leads him to conclude that whatever the hipper portion of the money-driven media tells him is the happening thing is what really counts in modern music. Consequently, he loved the Darkness when they first came out, only to disavow them a few months later when the opinion leaders of the British music press declared that they had become has-beens. The Youth Supremacist tends to mellow with age, particularly once he has exceeded the age of 25. Gradually the realisation sets in that he isn’t getting any younger. Commonly, Youth Supremacists counter the youth culture’s horror of the biological inevitability of physical ageing by shifting the boundaries of what constitutes “youth”: “So I’m 28 now. That’s OK. I’m still cool, I still keep up with the play.” “Wow! 32 already! But that’s OK - I still read the NME.” And so on. Youth Supremacists often mutate into latter-day versions of the Ageing Baby Boomer.

3. The Genre Specialist. This is the guy (they’re always males) on the staff who has a mania for a specific type of music. Regardless of changing musical fashions, or of what’s in and what’s out, he knows what he likes and he doesn’t give a damn what you think. The more obscure and insignificant the genre, the better: South African psychedelic music (nothing from after 1969 thanks), Venezuelan skate punk reggae, Mongolian doo wop - it doesn’t really matter, so long as he can enjoy the look of bewilderment on your face when he knowingly drops the names of bands you haven’t heard of. Anything that falls outside his hallowed musical ground is beyond the pale, and customers inquiring about releases by artists from other musical genres are met with cold condescension. Some of the most snobbish and scornful Genre Specialists are to be found in retail outlets specialising in jazz and classical music, while the most contemptible Genre Specialists are to be found in those small boutiques selling a select (narrow?) range of white label DJ-only dance music.

4. The Collector. This is a guy (they’re always males - are we beginning to detect a gender pattern here?) with an ever-expanding collection of recordings in all sorts of formats that were crowding him out of house and home. Rather than whack an extension on the house and run the risk of his long-suffering wife finally divorcing him, he decided it would be best to open a record shop. Conveniently, by going into business he can shift his prized record collection out of his house and away from his wife’s uncaring clutches AND write off his collected treasures as tax-deductible trading stock. Sheer brilliance! As actually selling bits of his prized collection is not a high priority, his shop is only open two days a month and once every fifth Sunday during leap years, or by appointment if you are a foreign collector from an affluent country with at least $2,000 to spend. The Collector has all sorts of obscure and interesting treasures, but these are hidden out the back in a store room, where no one can see them. The stuff out front on display is fairly ordinary, apart from a few choice items up on high shelves where customers can’t get their grubby paws on them. Should any unsuspecting clients venture to ask, they will be informed that they are display items only. Nevertheless, as he is a generous soul at heart, the Collector does have a few scratched copies of various rarities under the counter that he is prepared to sell, provided you manage to talk him around.

5. The Market Vendor. This character may deal out of a car boot, or from a fixed stall in a flea market. If he specialises in bootleg CDs, he may even sell from two well-stocked suitcases, ready to be grabbed in a hurry if the slack arm of the law catches up with him. Regardless of his trading platform, the Market Vendor’s combination of low prices and interesting items invariably leaves his customers wondering if the goods are dodgy or stolen. When buying from the Market Vendor, there is a golden rule: Always ask how much his unpriced stock costs before you start looking. Otherwise, if you do happen across that rare A&M Sex Pistols single and start salivating over it, he will knock the price up in line with his expectation of how much he thinks you are prepared to pay. As this assessment often depends on superficial factors like how you are dressed, doing the rounds of the markets with three-day stubble and wearing clothes so shabby that a tramp would turn his nose up can be a great help in securing a bargain or two. Oh, and keep your money in your socks - tramps don’t have wallets. The Market Vendor loves locals and hates foreigners, so if you can put on a convincing Cor Blimey Cockney accent in London, mumble Strine like a Cobber in Melbourne and speak French like a factory worker from St Denis when you are in Paris, so much the better.

6. The Ignorant Girl. Yes, she had to be mentioned, if only to avoid accusations of sexism, given that the last 5 stereotypes listed here were all males. The Ignorant Girl is around 20 or under, and is often the token female on the staff. She is both invariably pretty and knows nothing much about music, which leads to interesting speculation as to why the boss (usually an Ageing Baby Boomer) actually hired her. While it is true that she has mastered the art of pointing teenyboppers in the direction of Britney’s latest smash release, more complicated questions such as “where’s the audio DVD and SA CD section?” will be met with a confused smile and a response that indicates she doesn’t have a clue what you are talking about.

For all their faults and shortcomings, these strange characters are all to be treasured. Given that, with the rise of MP3s and on-line trading, the bottom is falling out of the bricks-and-mortar retail sector for records and CDs, you should enjoy their quirkiness in all its glory while you still can.

Forget The Models - Where’s

The Money?

31 October 2004

W.S. McCallum

Now and then I do that very un-rock’n’roll thing - tidying up around the house. In the middle of sorting out all the crap piled up on the top of the fridge (which, around my place, is a bit like the Bermuda Triangle for stray pieces of paper), I came across an article from the Dominion Post, dated 2 October 2003. In it, journo Tom Cardy interviews a very communicative Andrew Penman about Salmonella Dub. Even though it’s not exactly cutting news any more, it is a remarkable piece for delving into a topic that is normally taboo among musicians: MONEY. More specifically, it delves into Salmonella Dub’s finances.

Maybe Tom Cardy slipped Mr Penman one of those truth drugs. Maybe he just plied him with alcohol to get him talking. Whatever the reason, the result was a unique insight that, as far as I recall, passed uncommented on at the time, so I’m going to do it now.

Traditionally, rock musicians have no trouble talking endlessly (tediously?) about their harrowing ordeals with addictive substances, their even more harrowing experiences with rehab programmes, the models they’ve shagged, their traumatic childhoods etc. etc. etc. But money? Band finances? Strictly a no-no. Mum’s the word. Usually, it’s because they don’t want to admit publicly either (a) how much they’re earning or, more usually (b) how little they’re earning. Either way, it may be seen as very uncool. You know the sort of thing - if you’re a rap artiste posing on your latest album cover with some big-breasted booty girl and the latest model Porsche, the last thing you want your fans to know is that in real life all you can afford is a clapped-out Volvo and your real girlfriend is actually buck-toothed and works at McDonalds. Conversely, if you’re from some anti-establishment punk band that’s hit the big time, you don’t necessarily want the kids out in the street to know that off-stage you wear Armani, play the stock market and have a Swiss bank account.

Apparently Salmonella Dub have quite a way to go before they are up there with Green Day (just joking…). According to Andrew Penman, Salmonella Dub had a $90,000 tax bill in 2003. He didn’t state how much money they earned, but assuming they are operating as a company on a corporate tax rate of 33%, that would mean they earned taxable income of roughly $270,000. Mr Penman did however state that after paying three or four roadies and divvying up the remainder between the five members of the group, they each earn about $25,000 a year. In 2003 they all had day jobs, except Penman, who had taken a year off from his teaching job so he could work on the band.

Andrew Penman also declared: "For a New Zealand band at our level to earn an average wage in NZ, it would have to turn over $500,000 a year." Startling stuff, but quite logical when you think of all the overheads associated with keeping a group running, particularly touring costs.

Salmonella Dub’s latest tour of Australia (three weeks on the road performing 15 times) had cost them $140,000, while their concert returns amounted to only $160,000 - leaving a profit from door takes of about $20,000. (Before or after tax? He didn't say.) They only saved the day through merchandising - incredibly, they made $30,000 by selling clothing and other merchandise at gigs. In 2003, according to the article, Salmonella Dub wanted to do another European tour, but decided not to because of the tax bill that would be involved.

This is sobering information for young performers hoping to hit the big time. Salmonella Dub is a top NZ act, with a good international reputation, whose members went down the traditional path of gradually building up their image through hard work and good musicianship, established good international contacts in the business, and signed to a major record label. And yet look at where they are financially over 10 years after they started: still working day jobs because they can’t even make an average wage from their musical sweat and toil.

And if some readers are imagining that the logical conclusion to be drawn is that Salmonella Dub are poorly organised, then think again. Andrew Penman is an efficient organiser and an astute businessman. If this is the best he can do after over ten years of hard work based in New Zealand, it should give lesser mortals reason to stop and think.

We all know the stereotypical career path for making it in the music business - you slog away in order to establish your reputation, which wins you a contract with a major label, and then the money starts rolling in, after which you retire to your luxury mansion in some tax haven at the age of 35. And yet when you see members of The Headless Chickens stating on TV in Give It A Whirl that international fame and success here and in Australia left them around $150,000 in debt which, over 10 years later, they had managed to whittle down to less than $20,000, it would seem that there is a substantial gap between the myth and reality. And when you hear ignorant TV newsreaders beaming that Steriogram have made a US$500,000 video and are now a Big Thing in the States, do they or any viewers out in TV Land have any idea that things like expensive videos are usually charged up by the record company against royalties from the group’s recordings? Consequently if, at the end of their meteoric rise, proceeds from Steriogram’s CD sales haven’t covered this and all the promotional, recording, marketing and other expenses that the record company charges off against their royalties, then they will be in the same leaky, debt-ridden financial boat that the Headless Chickens were in when they hit the downward slope of commercial success in the 1990s.

So here’s my balloon-popping point to ponder. We are all hearing a lot about how “successful” the New Zealand music industry is these days, and about all the “recognition” it is garnering isn’t it wonderful blah blah blah. But how many Kiwi rock (rap etc.) bands performing and recording original material actually make a real living out of it? And how many of them can state with confidence that they will still be doing so five or ten years from now?

Not many.

Web site © Wayne Stuart McCallum 2003 - 2017